The development of technology is “inherently political”

The collective efforts of engineers throughout history have provided solutions to many of the world’s needs, but the current direction of our technological developments suggests that not everyone will be able to benefit from the fruits of humanity’s success.

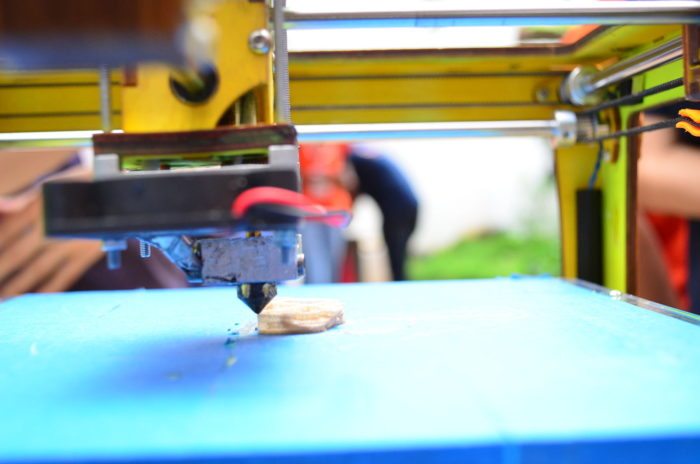

Today, laser cutting technology and 3D printers can work with polymers, metals, and even paper; organ printing and prosthetics are becoming increasingly commonplace. It is no longer inconceivable that one day, laser cutters and 3D printers will be household items purchased by the average consumer – producing all the things one will possibly need at the press of a button. In such a future, even the Med-bays of Elysium may not the stuff of sci-fi.

Image: Subhashish Panigrahi / Wikimedia Commons

When predictions made by prominent research institutions, say that 35% of existing jobs in the UK are ‘at risk of computerisation’ over the next 20 years, they do not refer only to the (true, but clickbait) stories of ‘60,000 factory workers replaced with robots‘. We are seeing technology not just taking the manufacturing jobs, but also jobs traditionally thought to be off-radar.

The solution is not a neo-Luddite quest to boycott and quash modern technology…

The advent of autonomous vehicles, artificial intelligence, and machine vision threatens the livelihoods of call centre workers/receptionists, kitchen staff, accounts managers, secretarial staff/clerks, inspectors, and one day, even lorry drivers. While unlikely to happen any time soon due to the limitations of current AI, the economic implications of AI taking the jobs of the one million call centre employees currently working in the UK is not a comfortable thought. In fact, Oxford University research suggests that even highly skilled workers are not safe; for example, research shows that accountants and auditors are at a 94% risk of automation (The Future of Employment, P.69).

All this isn’t hypothetical, but very real – even today. In 2017, Ocado runs a distribution centre with 8,000 automated containers at any one time. Ocado already operates a humanoid maintenance robot, SecondHands alongside their human employees. As we speak, they are testing a fruit-picking robot, no doubt concerning to the average agricultural labourer. In 2012, Amazon operated 1,000 Kiva robots in their warehouses; by the end of 2014, this number was at 10,000.

The solution is not a neo-Luddite quest to boycott and quash modern technology, nor is it Donald Trump’s delaying of the inevitable – deploying economic protectionism to “bring back jobs”. At the end of the day, low skilled workers in every country are at risk of automation.

Estimates suggests that by the 2030s five percent or more of UK jobs might be in areas related to new robotics or AI of a kind that do not even exist now. However, that in itself will not plug the gap of unemployment that further automation is expected to cause – equally, retraining an upper-middle aged workforce may not necessarily be an option.

In simple terms, as technology becomes more advanced and efficient, an ever fewer number of people will own more capital…

It may not be the engineer’s job to think about the structure of the world’s economy, but in the short run, we might see a phenomenon where the development of technology will exacerbate economic inequality. Professor Yanis Varoufakis at the University of Athens, describes this paradox succinctly, “the social inefficiency of capitalism is going to clash at some point with the technological innovations capitalism engenders”.

In simple terms, as technology becomes more advanced and efficient, an ever fewer number of people will own more capital and produce more services than ever before. Paradoxically, these commodities services will be sold to a population experiencing accelerated unemployment – due to technology replacing the human workforce that were formerly employed to provide such products.

The rate of unemployment in old, inefficient industries outpacing the rate of employment in new industries could lead to significant social unrest. Simply look at the American post-industrial towns today, where industries have left (as producing in Mexico/China is cheaper) and the government have been inadequate. Here we have seen huge issues of relative poverty and social dissatisfaction. Replace ‘producing in Mexico/China’ with ‘automation’, and result may be no different.

In the near future, the jobs that will stay are those requiring non-automatable skills, which the pay premium is expected to rise.

At present, whilst we are not at a stage where some utopian, fully state-planned economy is viable, significant voices in the private sector believe there is a case for some form of government intervention to ensure that the potential gains from automation are shared more widely across society.

In the near future, the jobs that will stay are those requiring non-automatable skills, which the pay premium is expected to rise. For the younger generation, governments need to focus on investing in education (and higher education) in growth areas, such engineering, digital technology, as well as sectors that are less easy to automate. For the older generation, PWC research also advises governments to focus on policy in vocational training and job matching, which will be vital for the reemployment of possibly 10 million in the UK, whose jobs are at risk of automation over the next 20 years. In the same paper, PWC even toys with the idea of universal basic income, but does recognise the associated issues of affordability and “potential adverse incentive effects”.

Einstein, before his death said, “I made one great mistake in my life – when I signed the letter to President Roosevelt recommending the atom bombs be made, but there was some justification – the danger that the Germans would make them”.

Our governments must be able to facilitate sustainable investment in education and training…

As the pioneers of cutting edge technology of tomorrow, scientists and engineers from both the private and public sectors must recognise the profound impact that their work has on society, culture and the economy. If mistakes are not to be made – mistakes that could negatively impact on society and the economy as a whole- the engineering profession must be engaged and active in public policy making.

Throughout history, legislatures and governments have been unable to keep up with technology, it is paramount that governments are clued up about the direction of technological growth – which is where engineers have a vital role to play. Former Education Secretary Michael Gove has spoken about this issue, so far providing additional funding for schools to teach coding and CAD, is a good (if baby) step forwards.

Our governments must be able to facilitate sustainable investment in education and training, whilst providing appropriate regulations, so that the economy is ready to adapt with more automation. For that reason, the development of technology is inherently political; engineers must know it and act accordingly – if generations after us are to live in a progressive society of our doing.

Comments