Should the biblical epic make a comeback?

Back in the fifties, the Bible was big business in Hollywood. Audiences used to flock to see big-budget and heavy-on-spectacle adaptations of Bible stories but, in much the way of the western, the genre effectively vanished from screens. We’ve seen a few biblical films as of late, but nothing rivaling the genre’s heyday – is the biblical epic due a comeback?

Noah’s Ark has become a set piece for biblical cinema

In order to answer this question, it may be worth taking a trip back in time. One of the first talkie films was Noah’s Ark, made in 1928. The spectacle was there from the off – the film ended in a flood scene that used so much water, it drowned three extras – and it generated the box office figures. It cost more than $1 million to make (Warner Bros.’s most expensive picture ever at the time, $14 million today) and grossed more than double.

The godfather of the biblical epic was the renowned filmmaker, Cecil B. DeMille. DeMille was born to religious parents (his father was a minister) who instilled in him a love for drama and theatre – these values became apparent as he carved a niche in Hollywood with his biblical epics. He’d made films like The King of Kings (1927) and The Sign of the Cross (1932), but it was 1949’s Samson and Delilah which really connected the Bible with the sheer scale of a DeMille film.

The godfather of the Biblical epic was renowned filmmaker Cecil B. DeMille

Still from The Ten Commandments. Image credit: Paramount Pictures

The Old Testament films grew bigger and more lavish, culminating with The Ten Commandments (1956). The film told the story of Moses (Charlton Heston) over three and a half hours, the film went big in its depiction of Egypt’s slaves, the ten plagues and the crossing of the Red Sea (a practical effect that remains impressive to this day). For DeMille, it was his swansong. Sadly, he would die three years later of heart failure.

1959 also saw the release of Ben-Hur, again starring Heston. The film is renowned for its chariot race, a spectacle that took five days and 15,000 extras to film. It went on to win 11 Academy Awards, the first movie ever to do so, and it effectively closed down the biblical epic, setting a bar that would never really be tackled again.

The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965) retold the story of Jesus Christ (Max von Sydow), and was criticised for the large ensemble cast, notably John Wayne as a centurion (von Sydow would later appear in a religious film of a very different sort, 1973’s The Exorcist). Then, religious films started to dry up. Jesus was again tackled by Martin Scorsese (The Last Temptation of Christ, 1988) and Mel Gibson (The Passion of the Christ, 2004, which proved to be a smash hit), but these were the exceptions. It seemed Hollywood had left the Good Book behind.

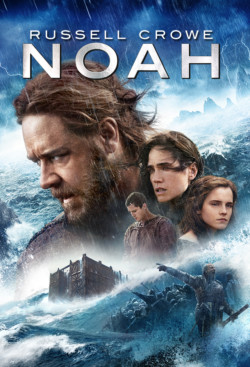

So, to the present day. We’ve seen some films inspired by the Bible; Russell Crowe starred as Noah in Noah and Christian Bale played Moses in Exodus: Gods and Kings, (both released in 2014). A remake of Ben-Hur was also one of the last summer’s blockbuster flops. They were slated for whitewashing, for their poor interpretations of the source material and for a general lack of creativity. Their reception has helped discourage Hollywood from pursuing religious films.

Yet there is arguably no better time to re-establish the biblical epic. Nearly a third of the global population (2.2 billion people) are Christians – that’s a huge demographic to target. Hollywood is notoriously unwilling to back unrecognised names and projects and, in the Bible, they have the most famous book in the world. As well as that, they also don’t have to suffer the issues of buying rights.

There is arguably no better time to re-establish the biblical epic

The Bible is often described as a collection of the greatest stories ever told, and some of the spectacles in the book are inherently filmic in nature. It seems a goldmine of material and, in a time where cinema attendance is falling, a truly cinematic biblical epic – one long enough and so full of spectacle it actually warrants the ticket price – could be what is needed to bring viewers back.

Comments