Guilty pleasures: What music makes Warwick guilty?

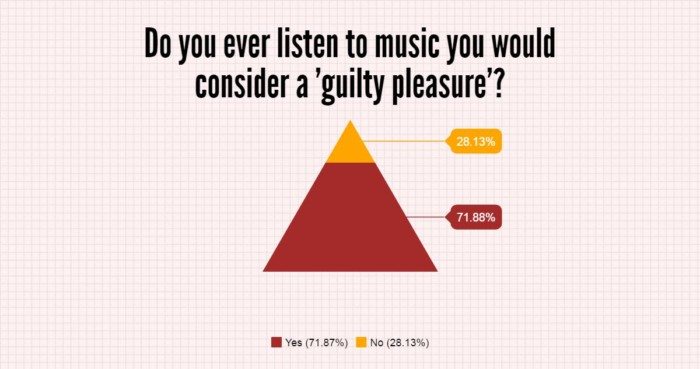

Most of us have guilty pleasures. The “guilt” that we feel upon enjoying certain music – whether it be Britney or Mötley Crüe – arises as a result of the pressure of the gaze of others; we are aware that these guilty pleasures contradict the image that we are, consciously or subconsciously, trying to cultivate of ourselves.

“It is difficult to uphold such a guise of nonconformity when the music industry is constantly churning out engaging, catchy tunes performed by attractive people”

There is something to be said about wanting to distance ourselves from music that is liked by the majority, perhaps because many of us like to see ourselves as unique and unconventional individuals. This is exacerbated by the fact that we may feel an element of competitiveness when it comes to developing our music taste, as we are increasingly encouraged to stand out from the crowd by flaunting a refined, personalised set of musical preferences, as an emblem of our supposed sophistication and good taste.

Nonetheless, it is difficult to uphold such a guise of nonconformity when the music industry is constantly churning out engaging, catchy tunes performed by attractive people. And even if you are one of the few to whom this sort of song doesn’t appeal, it is likely to be so overplayed that you grow to almost enjoy hearing it despite yourself, as you begin to associate it with happy memories – say, a good night out or your daily commute home from work. If this happens, the pleasure you take from it is bound to be marred by a slight sense of guilt.

“What may bother us about some pop songs is that they blatantly appeal to basic human emotions such as love, sadness and ecstasy”

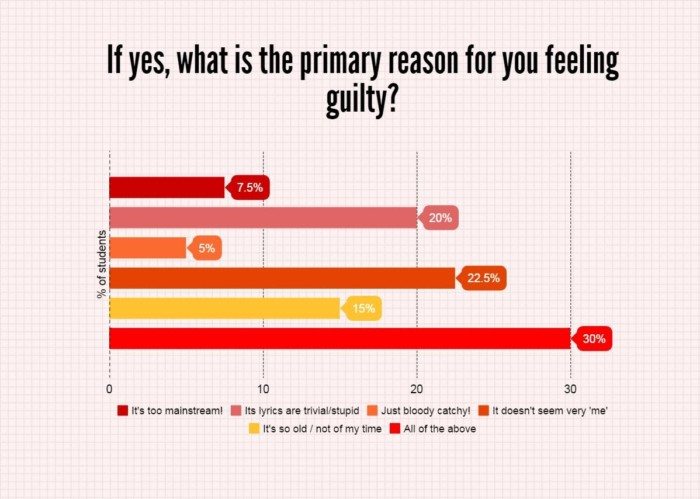

But what is it about contemporary commercial pop that makes our enjoyment of it taboo? It is implausible to put this phenomenon entirely down to the sheer simplicity or little artistic merit of the song in question – after all, lots of pop is critically acclaimed and has wide artistic and cultural impact. Part of our guilt may be rooted in the knowledge that it is produced for mass consumption and in order to maximise profit. Of course, musicians need to sell what they create for a living; but the issue here lies less with the artist themselves, and more with the music industry and the way in which it manufactures the music. When art emerges out of something other than genuine creative drive and talent, not only is authenticity compromised but, in turn, quality risks being minimised as a result of the artist’s limited input in the creative process.

It is this lack of authenticity – as exemplified by the legion of writers, producers, stylists, choreographers and musicians it took to deliver Beyoncé’s Lemonade (and indeed any of her albums) – that may lead to embarrassment about the music that one enjoys listening to, whether one considers it to be of artistic value or not.Alternatively, what may bother us about some pop songs is that they blatantly appeal to basic human emotions such as love, sadness and ecstasy. Whether it’s ABBA, Toto or the Beegees, we may feel this sort of music is unsophisticated due to a lack of lyrical or musical subtlety in its attempt to evoke emotion; or, we may simply be embarrassed by the collective tugging at heartstrings that pretty much everyone who listens to it experiences.

“It is not uncommon to feel a twang of shame for experiencing nostalgia in relation to a time that we did not live in.”

Less conspicuous, however, are the reasons for our aversion to enjoying critically acclaimed old classics that are widely lauded for their artistic and cultural merit. Often, these songs and their genres represent a certain lifestyle, a socio-political movement, or a subculture of the past – notable example, include gangster rap, punk, or the psychedelic blues-rock of the ‘60s. Many of us enjoy music that fits into these categories unflinchingly, namely because the songs that are remembered to this day are, quite simply, great songs.

However, it is not uncommon to feel a twang of shame for experiencing nostalgia in relation to a time that we did not live in. After burning £5m worth of punk memorabilia last year, son of the Sex Pistols’ ex-manager Joe Corre said “punk provided a way out for the No Future generation. It was never meant to be about nostalgia”. Perhaps part of what makes us feel guilty about enjoying this sort of music is the knowledge that we have nothing to do with the era in question and are excluded from everything about it except the superficial features that represent it, and therefore have no right to distill the aspects that we like about it and ignore the ones we don’t.

We might even feel that our misplaced nostalgia is an indicator of our individual inability, to a certain extent, to relate to the music of our own time. This worry is not helped by the fact that these superficial features of the past, namely the music and the clothes, are often shallowly re-popularised in the modern world and make brief reappearances in mainstream fashion and music. Sugar-coated and stripped of all its cultural significance, we may begin to associate the movement which this ersatz art seeks to imitate with falsehood and consequently, wish to distance ourselves from the other people around us who claim to enjoy listening to such music.

In presenting some of the reasons for which we might have guilty pleasures when it comes to music, I am not claiming that we should feel guilty for listening to what everyone else listens to, or for immersing ourselves in the music of another era. Rather, I believe that it may be difficult not to, with so many external pressures urging us on the one hand to fit in and on the other to distinguish ourselves from everyone else.

Anna Lancry

Comments