Murals and Politics: What’s the link?

Let’s be honest, street art is kind of the coolest. Don’t get me wrong, I can spend all day (and have) in a museum, appreciating everything from ancient artefacts to Dali’s surrealist paintings. However, you have to admire the talent and dedication that goes into creating street art in the most unexpected of places and how they can add a splash of vivacity to the most banal, everyday routine. But street art or murals are not always simply a welcome aesthetic pleasure.

Murals have always been popular, such as frescoes that have existed since antiquity in Aegean civilisations or Old Egypt for instance, but have most strongly been associated with the art of the Italian Renaissance with the breath-taking Sistine Chapel. There was also the important movement of Mexican Muralism which was started in the 1920s by the big three painters or “Los Tres Grandes”: Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros. It was immediately political as part of an effort to reunite the country after the Mexican Revolution under the new government, via murals depicting Mexican history.

Street art or murals are not always simply a welcome aesthetic pleasure.

Nevertheless, murals continued to be politically and socially crucial to the 1970s and in fact, to this day as their masterpieces are still on public display in Mexico. However, even on our very doorstep, murals in Northern Ireland have been an essential way to commemorate landmark occasions and changes in the country’s history, especially political events. Both New York and Berlin show simultaneously the importance of murals to the culture of city and how vulnerable they are. The demolition of the Queen’s iconic “5 Pointz” building and the white-washing of the Kreuzberg murals can cause us to wonder why murals are so popular for making a political point when they can be so easily removed.

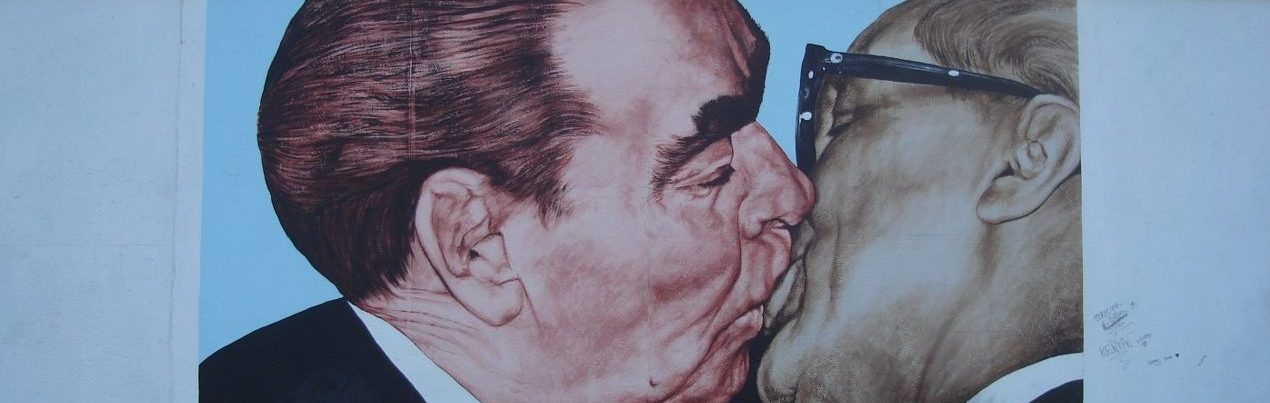

The ‘Kiss of Death”, appearing in Bristol weeks before the EU Referendum. Image: Robert Massey/Twitter.

With the current political climate, it’s unsurprising that a few new notable murals have popped up. Once upon a time, I would have laughed if anyone suggested ‘Donald Drumpf’ as a viable presidential contender, but now we are faced with the terrifying reality that he is the presumptive Republican candidate. It seems that I’m not the only one worried about this as a mural has been painted in Bristol featuring the once-unlikely candidate kissing the British politician Boris Johnson, who was a figurehead of the Brexit campaign.

The demolition of the Queen’s iconic “5 Pointz” building and the white-washing of the Kreuzberg murals can cause us to wonder why murals are so popular for making a political point when they can be so easily removed.

Political kissing figures are immediately reminiscent of the 1979 photo of former Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev and East German Chancellor Erich Honecker, which can be seen today on the Berlin Wall. The fame of this piece can immediately show why the group ‘We are Europe’ saw their version with ‘Drumpf’ as an effective tactic. Sharing a picture of the mural, which is called “The Kiss of Death”, on their Instagram page, the group wrote: “Like what you see? Didn’t think so […] Register to vote and we can avoid our very own kiss of death.” Although the above examples of graffiti in Berlin and New York can suggest that this is ineffective, it’s crucial to consider that the original success of politically motivated murals came from its immediacy, boldness and ability to reach a vast range of people from being a regular part of everyday life rather than stuck in a gallery.

In both the US and Britain, where fine art can often be stereotyped as belonging to the snobbish elite, street art is the domain of all.

But when it comes the resurgence of political murals, you can’t deny the importance of social media for making the ephemeral, permanent. It’s arguably the accessibility to street art makes it much more social media friendly and egalitarian than a regulated art gallery. In fact, that’s the beauty of street art, anyone and everyone can choose to create a mural as you don’t even have to identify yourself. In both the US and Britain, where fine art can often be stereotyped as belonging to the snobbish elite, street art is the domain of all. It is therefore unsurprising that murals have become a popular political tool. It even appears that images like the kissing political figures or the work of other artists like Banksy, stay in the public’s consciousness much more vividly. I suppose the question really is, for all the effectiveness of murals and their long history, why does the general public still not give them the serious reputation of fine art in a gallery? After all, it’s sometimes the location of the mural that gives it some of its impact.

Comments