Does UK science have a future without the EU?

Even though we’re still a month away from the big day, you can’t go anywhere without some mention of the Brexit debate. The discussion is often centred on the usual politics – immigration, jobs, the NHS – but an important aspect to consider as students is the future for us and our subjects. So what’s Brexit like for science?

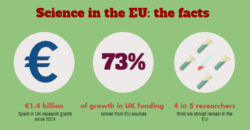

It’s crucial to understand what benefits the UK scientific community get from our membership of the EU. The figure of EU membership per week often banded around is £350 million, but doesn’t take into account our rebate, which brings the cost down to somewhere around £250 million. We then get money back in several ways – most relevantly perhaps, for this article, in the form of research grants. Without these grants – which have totalled over €1.4 billion since 2014 – a lot of the work done by academics at universities across the country simply wouldn’t be possible. That includes the work of the Manchester Nobel Laureates who discovered graphene – the funding they have received to develop their breakthrough over the next ten years came from the EU. The funding for 17% of the scientific research in the UK now comes from EU sources, and an enormous 73% of the increase in higher education scientific research funding comes from the EU.

It’s crucial to understand what benefits the UK scientific community get from our membership of the EU. The figure of EU membership per week often banded around is £350 million, but doesn’t take into account our rebate, which brings the cost down to somewhere around £250 million. We then get money back in several ways – most relevantly perhaps, for this article, in the form of research grants. Without these grants – which have totalled over €1.4 billion since 2014 – a lot of the work done by academics at universities across the country simply wouldn’t be possible. That includes the work of the Manchester Nobel Laureates who discovered graphene – the funding they have received to develop their breakthrough over the next ten years came from the EU. The funding for 17% of the scientific research in the UK now comes from EU sources, and an enormous 73% of the increase in higher education scientific research funding comes from the EU.

Being in the EU also allows us to give our say on the way science is done across the whole of Europe. A brilliant example of this came about when the Clinical Trials Directive was reformed; in the reform consultation 22% of the responses were from UK institutions, with a further 29% from international consortia that included British members. This amplification of our nation’s voice on big decisions that have profound effect on the research performed by scientists in this country shouldn’t be underestimated, and it would almost certainly be curtailed if the UK were to leave the EU.

What else would we stand to lose if the electorate voted in favour of Brexit on June 23? A clue could come from what’s happened to other countries who have severed ties with the EU in some way. Take Switzerland, for example, who voted to restrict the free movement of people in 2014: the share of EU collaborative projects that Swiss institutions were in control of shot from 3.6% to just 0.3%. Let’s not sugar-coat it – it was bad news for Switzerland, and if that happened to the UK we would certainly take a blow.

So how does any of this relate to you? Quite simply, nobody knows what a future UK would look like outside of the EU, but the likelihood is that any money saved in membership fees won’t be used to match research grants like-for-like. In turn, this probable dip in funding could easily have a negative impact on your departments – with less money, universities generate less research. Less research will surely have an impact upon your degree: without research opportunities, a worst-case scenario could see a brain drain from UK universities to other, better-funded parts of the world, and with that, the quality of academic departments would certainly suffer.

Quite simply, nobody knows what a future UK would look like outside of the EU

Before June 23 take a moment to think – to really think – about the consequences of the cross you put on your ballot paper. Although it’s easy to get caught up in the big politics of the debate, it’s important to remember that there are many areas – of which science is one – that would be much the poorer if Brexit goes ahead.

Comments