Psychoactive substances: the end is high

A new law is set to criminalise the sale of ‘psychoactive substances’, otherwise known as legal highs. Although the possession of legal highs won’t be illegal, the supply, possession with intent to supply and importation of the substances will be. Not only will these be criminal offences, they’ll also carry a hefty maximum sentence of up to seven years imprisonment and/or a fine.

The legislation – delayed from 6 April – finally came into force yesterday (26 May). After the bill was written into law in January, the delay came after claims that the bill was completely unworkable in its current form. The issues included a definition of psychoactive substances that critics have claimed is completely unenforceable – according to Police Scotland, every single case would require a medical expert to prove whether the substance was psychoactive or not. Similar legislation was introduced in Ireland in 2010, and the same issues were also experienced.

Further complaints have been made by those in scientific research, as drug licences will be required in order to carry out tests with the newly-prohibited substances. Other criminalised drugs, such as LSD and ketamine, have already been found to have the potential for use as anti-depressants. It’s thought that by making research into all psychoactive substances more difficult, the amount of research into helpful uses for them will fall, meaning that possible advantages of the drugs could simply go to waste.

Alcohol, caffeine and nicotine have all been exempted from the legislation

Some things have escaped from being incorporated into the bill though – alcohol, caffeine and nicotine have all been exempted from the legislation, among others. Other laws prohibiting drug use are also unaffected by the ban.

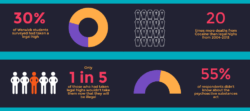

Here at Warwick we asked students about their usage of legal highs to find out the impact of the impending ban. The results show that 30% of respondents have used legal highs at some point in the past, with 76% of those who have previously taken a legal high willing to take a drug of this kind again in the future, regardless of the new legislation. It seems then that the new law won’t make much of a difference to the attitudes of Warwick students – the main impact will most likely be felt with any disruption to the supply chain that any enforcement causes.

Interestingly, the majority (55%) of those surveyed didn’t know about any changes to the law around legal highs, including almost a third of those that had used legal highs. Moreover, some nootropic substances – usually known as study drugs – are banned by the new act, which could certainly have an impact upon users within the Warwick community. All of this shows that the communication of new laws to those affected by them should be greatly improved.

What difference will the new law make? Karen Bradley, a Home Office Minister, said: “Psychoactive substances shatter lives”, calling their sale “an abhorrent trade”. While legal highs have been an increasing cause of death – particularly among young people – there needs to be some perspective when talking about criminalising substances in such a wholesale way. The deaths in England and Wales somehow attributed to legal highs between 2004 and 2013 stand at only 76 – that’s 20 times less than those caused by Cocaine, and 100 times less than Heroin or Morphine.

there needs to be some perspective when talking about criminalising substances in such a wholesale way

Furthermore, the ONS found that 60% of the deaths involving legal highs also involved alcohol or other drugs. The issue is more complex than simply the consumption of legal highs – the problem lies in the lack of education given to people using the substances, and the inability of users to know exactly what is in their chosen drug. By introducing controls on psychoactive substances in place of a ban, the drugs supplied and their effects could be studied and regulated in order to improve the safety of users without causing the issues that a blanket ban such as the new law provokes.

The idea seems to be that, by banning these substances, the number of deaths caused by them will also fall. Although it seems like common sense, data from the Office for National Statistics questions this; when MCat was banned in 2010, death rates actually continued to increase. The truth is that simplistic drug policies won’t solve a complex problem, contrary to what the Government believe.

Comments (1)

Good article. Politicians should fear the people and not the other way around, this act turns common law on it’s head and nobody cares. Next up is the extremism act.

The UK is heading for a very, very dystopian future and I’m jumping ship, living here is a joke; carrying pepper spray means you’re in possession of a firearm, lock-knives (which are tools) are illegal and much much more not to mention gun control gone mad.

Next up is the extremism act, which bans any ‘extremist speech’; I’d say more but the sound of Orwell and Huxley spinning in their graves is giving me a headache.