The best closing lines in literature

‘And you say, “Just a moment, I’ve almost finished If on a winter’s night a traveller by Italo Calvino.”’ – Italo Calvino’s If On A Winter’s Night a Traveler

Calvinos’ endlessly playful postmodernist masterpiece, which begins with him telling you that you, the reader, have begun reading the book, brings things to a close in the only way that makes sense: by telling you, in a comically deferred way, that he has brought things to a close.

‘And when he came back to, he was flat on his back on the beach in the freezing sand, and it was raining out of a low sky, and the tide was way out.’ – David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest

This is  what we come to at the end of the half a million words that make up David Foster Wallace’s monumental modern classic. It has led us through a drug rehabilitation clinic, an elite tennis academy filled with genius-level stoner teenagers, a group of wheelchair bound French-Canadian assassins and a film so entertaining that anyone who watches it loses their capacity to do anything else.

what we come to at the end of the half a million words that make up David Foster Wallace’s monumental modern classic. It has led us through a drug rehabilitation clinic, an elite tennis academy filled with genius-level stoner teenagers, a group of wheelchair bound French-Canadian assassins and a film so entertaining that anyone who watches it loses their capacity to do anything else.

Now we finally arrive at a scene where Don Gately wakes up after being knocked unconscious in a particularly terrible event that was to lead to his recovery from addiction, prior to the events of the novel. Its sparseness and mysterious poeticism is in direct contrast to the manic events the reader has spent such a long time being rushed through – it matches our feeling of waking up after a bizarre, lengthy, and chaotic dream.

‘On the morning of October 13, for example, 175 wrens had been gathered in, all dead of the impact, although the night just past hadn’t been particularly windy or dark.’ – Teju Cole’s Open City

Another acclaimed contemporary work, the Nigerian novelist Teju Cole’s story of immigration, modernity and adriftness ends with this strange account of birds in New York being killed by the disorientatingly bright light of the Statue of Liberty’s torch.

It is a melancholic statement on the difficulties of modern America, a country forged by immigrants, but which is all too frequently cruel and unwelcoming to those who fall outside its current white majority.

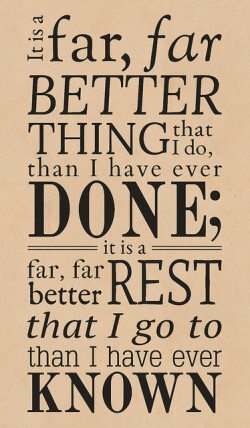

‘It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest that I go to than I have ever known.’ – Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities

Dickens begins and ends this novel with anaphora, the literary technique of doubling, which reflects the doubles and parallels that run through the book (London and Paris, the characters Carton and Darney, etc.).

Here, we see Carton willingly give his life to save his doppledanger Darney by taking his place to be executed. Carton has progressed from being a cynical, selfish alcoolic to being an idealist who is valiantly willing to give his life for the greater good: a sincere and powerful end to a brilliant story.

‘But the effect of her being on those around her was incalculably diffusive: for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs’ – George Eliot’s Middlemarch

Middlemarch’s ending stands in stark juxtaposition to A Tale of Two Cities: it isn’t about someone becoming a martyr in the course of a violent national revolution, but about those who are heroic in a smaller, day to day sense. It is all about the quiet heroism that you won’t find in history books, but about the kind that you will find again and again in life and great novels.

Image Credits: Flickr / quattrostagioni (Header), Flickr /Alper Çuğun (Image 1), Flickr / Zak Kolar (Image 2)

Comments