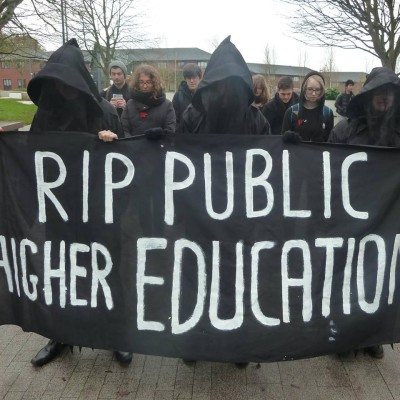

Free Education: is it moving anywhere?

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]t’s easy to have the right sentiments; to smell injustice and try to change things. I applaud this behavior – political engagement is undoubtedly a good thing. However, I become frustrated when people attempt to translate these attitudes into effective policies. For me, the most explicit example of this failing is the various Free Education movements, with half-baked policies and ineffective demands.

They fail to translate their principles into policies. The notion that education should be accessible for all is the cornerstone. Essentially, one’s financial background should never prohibit one from going to university. This is not a divisive opinion. You would have to be a truly vindictive person to argue against that.

With this established, the question is this: what is the best way to enable those from the lowest income backgrounds to go to university? The movement’s answer is no fees, no cuts, no debt and living grants for all.

If we looked at education in a vacuum, all those demands would be great. but we can’t simply do that. If the government chose to allocate more resources to higher education, then it would have to neglect other vulnerable members of society, such as pensioners or the disabled.

If there was ever a demographic that could bear some more costs, it would be students (young people with long working lives and higher potential incomes). Fear-mongering has warped public perception of tuition fees – in reality they aren’t a bad thing.

Admittedly, it’s daunting to leave university with £27,000 of debt, but this is a false narrative. University is free at the point of access. When you leave, you just have reduced pay. People don’t worry about paying income tax in the future so why are tuition fees any different?

When you unpack the demands of the movement, it’s easy to see that the majority of their policies are unhelpful. Abolishing tuition fees might not even encourage more disadvantaged students into higher education. Look at Scotland, where the SNP claim to advocate social justice since they don’t have fees for Scottish students.

The reality is that less disadvantaged students apply for Scottish Universities than English ones, because when they abolished tuition fees, they allegedly also had to cut Scottish student support grants by £40m. Free tuition in Scotland doesn’t actually help the poorest – it just subsidises advantaged middle class students who would attend regardless of tuition fees.

They also advocate relaxing borders to higher education in the UK – meaning foreign students would enjoy the same exemption from tuition fees. Undoubtedly, this would further crowd out British students (particularly disadvantaged ones) from university placements.

There would be a huge influx of foreign students, like (potentially) American students, who are notorious for exorbitant fees. Why wouldn’t they apply to British universities and return home with little or no debt?

Competing for places would then become even harder than it already is, especially for the most disadvantaged. To be clear, I have no intention of trying to deliberately block international students from studying in the UK. However, this would be to the detriment of taxpaying British families, and there’s no justice in that.

Helping and encouraging the disadvantaged go to university is where policy should be focused. This is why the recent conversion of grants to loans by Cameron’s government is deplorable. Giving more debt to the most disadvantaged students is perverse, and borders on sadistic. The government should want to do everything they can to encourage people from the poorest demographics to apply for higher education.

By not thinking through policy, their values have been undermined. If the same amount of energy was poured into thinking about issues as it is into campaigning for them, the left wouldn’t have a problem winning the hearts and minds of people.

But they don’t, and neglecting this fails the people they want to help most. Their principles become little more than a sentimentality, which, when inspected closely, starts to crumble.

Comments