Magna Carter and King John: An Interview with Stephen Church

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]’ve only been sitting next to Stephen Church for a few minutes but already I’m in awe of how much information he has managed to fit inside his head. I suppose it is his job though, being a professor of medieval history at the University of East Anglia. Stephen has travelled to the Collection Museum, in Lincoln, in order to release his book, a biography of King John – King John: England, Magna Carta and the Making of a Tyrant. Along with the eighty-plus people waiting in the foyer outside to hear Stephen’s lecture, I am intrigued as to how someone even starts to uncover the real life of a King already so well-established in popular culture as a murderous villain. Sitting in the staff room before his talk begins, Stephen tells me.

“John was the subject of my PhD thesis,” he says. “I also published a book about his household knights and then another collection of essays at the end of the 1990s. It was then that I thought that I really ought to produce something ready for Magna Carta year.”

“John was the subject of my PhD thesis,” he says. “I also published a book about his household knights and then another collection of essays at the end of the 1990s. It was then that I thought that I really ought to produce something ready for Magna Carta year.”

2015 is a big year for King John, despite the fact he’s been dead for 799 years. The Magna Carta – the ‘Great Charter’ – famously signed by the underachieving King, celebrates its 800th birthday this year. Only four copies of the document remain, one of which is kept by the Lincoln Cathedral. After spending a few years at the British Museum in London, where it was reunited with the other three copies, the Magna Carta returned to Lincoln in early April in order to coincide with the opening of the newly refurbished Lincoln Castle.

This is the year people are going to be reading about King John.

“One of the things we want, as academics, is for people to read our work,” Stephen says. “It’s nice to sell lots of copies and the financial reward from that is great, but you want people to read what you think. This is the year people are going to be reading about King John. The way that I sold it to my agent was to point out that there will be books about Magna Carta but what we really need is the context. The context of Magna Carta is John’s reign, so that’s what I set out to write in my biography.”

“One of the things we want, as academics, is for people to read our work,” Stephen says. “It’s nice to sell lots of copies and the financial reward from that is great, but you want people to read what you think. This is the year people are going to be reading about King John. The way that I sold it to my agent was to point out that there will be books about Magna Carta but what we really need is the context. The context of Magna Carta is John’s reign, so that’s what I set out to write in my biography.”

I, probably like most other people, already have an image of King John in my head, drawn from Robin Hood films. If it’s not the cowardly lion from the animated version, in which Robin Hood is a fox, its Toby Stephens from the BBC series, flamboyantly dressed, opening his arms and shouting in a camp fashion: “Do you LOVE me?”. However, as Stephen points out in his lecture, Robin Hood and King John, although now seemingly linked together as protagonist/antagonist, were only really connected in the 19th century, with Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe. The picture Stephen paints of John is different. Certainly not good, but different.

“John is a spectacular failure,” Stephen tells me. “I think spectacular failures can be really interesting. What I find interesting in particular is how power is abused by people, whether they are 21st century prime ministers or 12th century kings.”

“What I find interesting in particular is how power is abused by people, whether they are 21st century prime ministers or 12th century kings.”

What strikes me later, as Stephen gives his lecture, is how different England was during John’s reign. When crowned, John wasn’t just king of England but also a vast region of France, stretching from Normandy all the way down to Toulouse in the South. Of course, being the spectacular failure that he is, John managed to lose all of it. He also managed to fall out with the Pope, then the most important person in Christendom, who went on to excommunicate the whole of England. The last of the conquering Angevin dynasty, John did have a tough act to follow, succeeding his warrior-king brother, Richard the Lionheart. Even the nature of kingship was completely different to what I expected; John was constantly on the move, travelling 12 miles on horseback a day, with his entourage of 1,000 people and 500 hunting dogs. As I listen, I can’t help being reminded of Game of Thrones. Even Stephen admits that John could be seen as something of a ‘Joffery’ character. This said, as Stephen described John’s formidable mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine and the events that led John to killing his own nephew, Arthur, it seems almost more bloodthirsty than Game of Thrones, albeit with fewer dragons. After all, fact is stranger than fiction.

800 years is a long time, and yet these ideas and principles are still important today.

2015 is only a year. Soon the hype surrounding John and the Magna Carta will pass, although it will never lose its significance. Stephen, however, is prepared. His next project is a biography of John’s son, Henry III, for Penguin.

2015 is only a year. Soon the hype surrounding John and the Magna Carta will pass, although it will never lose its significance. Stephen, however, is prepared. His next project is a biography of John’s son, Henry III, for Penguin.

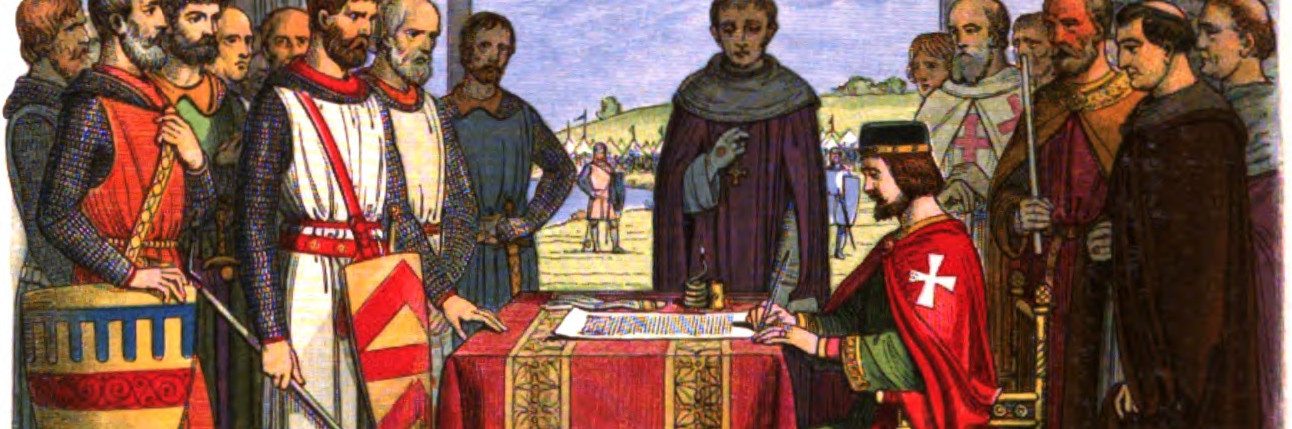

“The line I want to take is that it’s a new form of monarchy,” he explains. “It’s the time of a new thought in Western Europe: kings are not able to treat kingdoms however they want. There are a lot of people that have a stake in the kingdom and these stakeholders should have a say in how the kingdom is run.”

800 years is along time, and yet these ideas and principles are still important today. Various parts of the Magna Carta were used in the American Declaration of Independence, in The Vindication for the Rights of Women and in our government today. King John, Magna Carta, power and so on are all fascinating to learn about, as can be grasped from the buzz of chatter around me as I leave the lecture.

“Yes,” says one man, his voice raised slightly. “But was he really a tyrant?”

If he wants the answer, he’ll have to read Stephen’s book.

Image Credits: Header (en.wikipedia.org), Image 1 (en.wikipedia.org), Image 2 (Photo: Ellen Lavelle), Image 3 (commons.wikimedia.org)

Comments