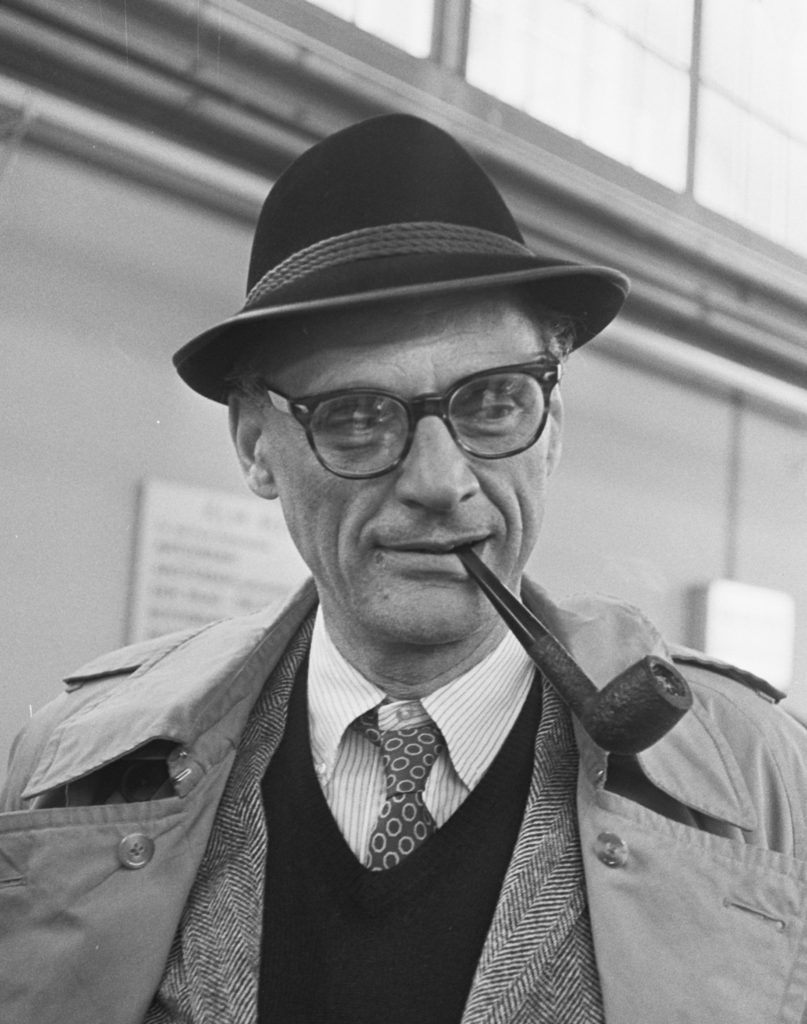

Arthur Miller hits 100!

Theatres and audiences alike have rediscovered their love for one of America’s greatest playwrights – and just in time for his centenary.

Over the last twelve months, with three of England’s most popular and reputable theatre companies choosing to revive some of his most influential works, Arthur Miller seems to be enjoying somewhat of a renaissance. The Old Vic’s brutal production of The Crucible and the Young Vic’s stylised reworking of A View from the Bridge were two of the most highly-acclaimed productions of last year. Both featured heavily at this year’s Oliviers, with the latter taking home the Best Actor, Best Director and Best Revival awards. With the RSC’s production of Death of a Salesman confirmed to transfer to the West End, I imagine it’s going to be a while before we are no longer able to see this man’s name radiating from the billboards of the capital. It feels rather apt that this should happen now with his 100th birthday looming and it is only right that we examine just what it is about this man’s work that has always and will always captivate us.

Recounting her experience of working with Arthur Miller during the 2002 Broadway revival of The Crucible, actress Laura Linney refers to him as ‘probably the smartest man I’ve ever known’. The ‘searing’ nature of his mind, as Linney puts it, is probably rooted in the fact that Miller was a published academic and theorist as well as a dramatist with his knowledge of his own craft surpassing that of many of his contemporaries. In his ‘Tragedy and the Common Man’, he argued that ‘the common man is as apt a subject for tragedy in its highest sense as kings were’ and was able to redefine the genre by directly employing this vision throughout his work. His utilisation of classical tragic convention combined with modern, accessible characters allowed for the necessary evocation of the Aristotelian passions of fear and pity without using archaic language, lengthy soliloquys and exhaustingly multifaceted plotlines which deter many prospective theatregoers from experiencing Shakespeare and classical Greek tragedy.

This renders Arthur Miller’s works particularly accessible to modern audiences. He presents universal themes in a way that any audience can relate to and in a language that they can understand. Willy Loman, Eddie Carbone and John Proctor’s shared willingness to risk death for the sake of their ‘name’ is an inflated representation of something which we can all relate to. Loman’s desperate need to leave his mark on the world through his sons, Carbone’s overbearing protectiveness of his young niece and Proctor’s yielding to sexual temptation are just a small number of issues that allow the content of these plays to remain relevant decades after their initial staging. Besides their universal themes, these twentieth-century American dramas seem to possess a particularly profound resonance considering the political and social climate of Britain today. In the context of this year’s election and the flood of political rhetoric that comes with it, Miller’s plays are just as relevant to our society as they ever could be: Salesman’s examination of capitalism and increased competition for employment, Bridge’s portrayal of the motivations and hazards of immigration and The Crucible’sdepiction of a fractured community governed by lies, corruption and driven by a mistrust of flawed authority figures.

In his centenary year, Arthur Miller has been granted a well-deserved and well-orchestrated revival. The public, artists and critics have all been sufficiently reminded of why this man is considered one the greatest and most influential literary figures of his generation. His relatable characters, his consistent relevance and the sincere emotion he is able to draw from his audience are just a sample of reasons why we will still be reading, viewing and performing his plays in another hundred years to come.

Comments