Study-enhancing drugs surge in popularity

The Boar conducted an anonymous survey of Warwick students to investigate how many students are taking so-called ‘smart pills.’

Recent reports from the Guardian suggest more students at British universities are turning to performance-enhancing pills when studying.

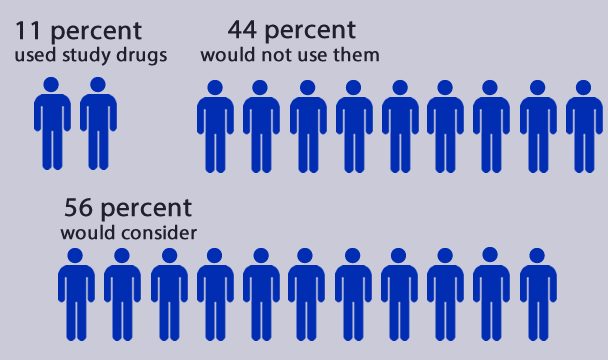

The Boar asked 209 Warwick students about their experiences with and opinions of study drugs. 11 percent of respondents had used study drugs, and a further 56 percent said they would consider using them.

When asked whether or not there was an unfair advantage to them of other students using drugs, 41 percent of those surveyed said there was, 41 percent thought there wasn’t, and 18 percent were unsure.

The survey also found that the proportion of study drug users rises to 20 percent when looking at second-, third- or fourth-year students. Meanwhile, only 5 percent of first-years claimed to have used study drugs.

Study drugs are usually bought on the internet or supplied by a dealer on university campuses.

The drugs, termed ‘nootropics’, are cognitive-enhancers originally developed as treatment for long-term illnesses such as Alzheimer’s disease, but they have been increasingly re-purposed and sold as concentration-enhancing pills or ‘smart drugs’.

One of the most popular in the UK is Modafinil, a prescription-only medication for narcolepsy, which acts as a stimulant to prevent excessive sleepiness, according to the BBC. Side effects can include prolonged anxiety, headaches and digestive problems.

The rising popularity of the drugs derives from the United States where usage reaches 25 percent of the student body in the most academically competitive universities, according to a 2005 study by the US National Centre for Biotechnology.

Although it is not considered addictive, studies have shown that Modafinil can increase levels of dopamine in the brain’s reward centre, which has been linked with addiction, according to the Guardian.

A second-year undergraduate who had used study-enhancing drugs, commented: “I love them, they help me concentrate so much better. At the end of the day, if people think they give others a disadvantage, it’s not like they’re hard to come by so [they] could get them themselves too.”

A third-year undergraduate, who said that they would not consider using study drugs, compared them to performance-enhancing drugs in sport: “If athletes are prohibited from placing themselves at an unfair advantage via substances, I feel that the same should apply in academia.”

A first-year undergraduate who had not used study drugs however said that they did not feel at a disadvantage to those who did use them.

They said that the issue was not to do with increasing intelligence, but concentration: “Some people are naturally more able to concentrate than others. Is that an unfair disadvantage?”

Warwick University’s head of press and policy, Peter Dunn, commented that the University did not identify the use of study drugs as a significant issue for Warwick.

He said that in cases where it was a concern, “it is an issue that the University Support Services and Students’ Union services would deal with on an individual basis with a student.”

Comments