Rosetta’s lander reaches final comet destination

After ten years of waiting, the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Rosetta spacecraft has launched itself into the history books by becoming the first space mission to land on a comet.

However, things haven’t exactly run smoothly for the ESA team. Several problems have been encountered since the craft’s delayed launch in 2004, the most recent being the landing itself. Rosetta’s robot companion, named Philae after a lake in Egypt, weighs only 100kg; due to the comet’s weak gravitational field, Philae could only afford to make contact with the surface at walking pace, to avoid simply bouncing off the comet.

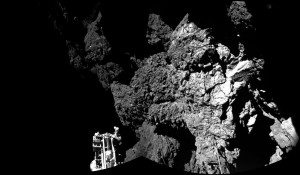

Unfortunately, this is exactly what happened; Philae rebounded twice from the comet (the first reaching 1km in altitude, the second reaching 12 metres) before managing to recover and bring itself to rest, some way off its intended touchdown site. Even now, after landing safely on the comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, things are still uncertain for Philae. The actual landing site is in an area with a low amount of sunlight – under some sort of cliff – which could cause problems for power generation for the scientific instruments onboard.

But why are we so bothered with landing a chunk of metal on a ball of ice and rock half a billion kilometres away? Is it not just a magnificent waste of time – with a €1.4 billion (the equivalent of three Airbus 380 jets) price tag to match?

The answer to that is simple: comets may be able to unlock the secrets of not only how the Earth and Solar System began, but also of where life may have begun and how these things may have developed until today.

Comets are popularly known as dirty snowballs due to their ice content – and it’s this ice which is such an exciting prospect for space research. It is thought that Earth’s water might have been acquired through numerous impacts from comets and asteroids in the planet’s infancy; some scientists even propose that the organic materials necessary for life came from these wanderers of the solar system. If Philae were to detect signs of organic matter (such as amino acids – the building blocks of life) on 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, it would be a pivotal moment for our understanding of what lies beyond our planet – it would confirm the possibility of the existence of other objects in the Solar system that could harbour the potential for life.

Furthermore, ESA could bring us more practical applications from this landmark mission. As the first probe to send back images from the surface of a comet, Philae may be able to further our understanding of how solar wind (a stream of high energy particles ejected by the Sun) interacts with the comet, which could have implications on how we shield future manned space explorations from this hazardous ‘space weather’. Revolutionary new solar technologies were also developed for Rosetta so that it could continue to provide power for itself in the far reaches of the solar system, where there is only 4% of the sunlight we get here on Earth. The wealth of knowledge and these practical applications together more than justify the seemingly large price-tag.

It has been some time since a mission such as Rosetta has captured the imagination of not only the scientific community but also the public, and this could be the start of a new chapter in space exploration – to involve people far and wide in the search for understanding within our solar system. However one thing is certain: the incredible work of the ESA team has produced a milestone we can all applaud.

Comments (1)