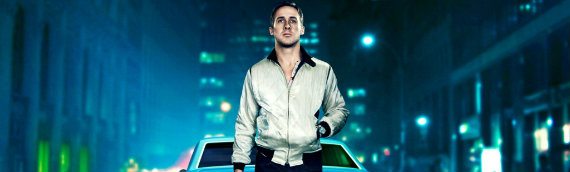

“Drive” rescored

Some of the songs written and recorded for the BBC’s Zane Lowe-curated Drive rescore project are undoubtedly captivating and energising, but once retrofitted to Nicolas Winding Refn’s iconic neo-noir visuals, they feel sorely out of place.

Opener ‘Get Away’ gives the same catchy electropop feels as the majority of CHVRCHES’ debut album The Bones of What You Believe did, but cutting away from an ice-cold Ryan Gosling to that famous topographical aerial shot of night-time Los Angeles has none of the same impact without the jolting four-on-the-floor beat of Kavinsky’s seminal ‘Nightcall’. Maybe for those who had previously never seen Drive but chose to check out BBC3’s broadcast of it just to hear new music from their favourite indie bands, such instances represented moments of joy; but for me, and I imagine for many others who had already seen this movie a number of times, this first encounter with Lowe’s new score brought a sour taste that lingered for the duration of the film.

Generally the new score gave Drive a distinctly brighter tone, but sadly this left me with the sense of a less unified aesthetic, given the deep melancholy and chaotic violence that characterises the film. The odd feeling that sound and image had become somewhat spliced and detached from one another illuminates a truth that many had already suspected: that movies are not simply made cool by cool songs, but by a careful merging of soundtrack, screenplay and mise-en-scene into a vibrant, coalescent whole. Not many films from the past decade have mastered this act quite so well as Drive; if there is one other, I would argue it’s Harmony Korine’s Spring Breakers, which not coincidentally was also scored by Cliff Martinez. While Zane Lowe clearly has a great ear for music, his is not linked so intrinsically to a cinematic consciousness as Martinez’s is: djing and tastemaking are entirely different skills to scoring.

Generally the new score gave Drive a distinctly brighter tone, but sadly this left me with the sense of a less unified aesthetic, given the deep melancholy and chaotic violence that characterises the film.

That’s not to say that Lowe’s project is at all bad for a first attempt. In fact there are moments of improvement to the original version. The montage sequence in which Gosling’s anonymous driver takes Irene (Carey Mulligan) and her son Benicio on a trip to throw stones into the river is perhaps the most outwardly happy of the film, and in the rescore this mood is more significantly uplifted by the tropical chillwave flavours of The 1975’s track ‘Medicine’ than it was by the music used in the original.

But what is most painfully lost in this musical reinterpretation of Refn’s film is College’s iconic song ‘Real Hero’. In the film as it was originally scored, this track faded dreamily in and out of the spectator’s consciousness, serving not only as a tonally rich refrain, but also as a reminder of the values and philosophy at Drive’s emotional centre. This is a centre that, with so little dialogue and clear subtext, can be frustratingly hard to break into for many first-time viewers of the film, but what was made clear to me from watching the BBC’s update was how important a role the moody, synthetic pop songs played in telling us what the characters would not: how they feel.

There is first of all the direct link between the detached psychological study of the driver and the College song’s lyrical focus on what it means to be a ‘real human being / and a real hero’ – is Gosling’s protagonist a motivated and well-meaning crime-fighter, or merely a spectral drifter, cool to brutal violence and numb to the touch of others? As far as almost equally mute love interest Irene is concerned, we are given the hypnotically miserable Desire song ‘Under Your Spell’, which plays at her boyfriend’s (Oscar Isaac) welcome home party, but suggests through its evocations of painfully frustrated lust (‘I don’t eat, I don’t sleep / I do nothing but think of you’) that it is not the father of her son, but the mysterious car mechanic next door she is in love with

The point this experiment in film music raises is that good songs do not a good soundtrack make. What makes Drive one of the best-soundtracked films of its generation is not the quality of its songs, but the genius method behind their selection. Beyond the psychological illuminations provided in the lyrics, there are stark parallels in iconography that heighten the movie’s atmosphere and style, none moreso than that between the protagonist’s attire and occupation and those of the very similar character ’Nightcall’ producer Kavinsky created for his own album, which focused on a ghostly auto-driver and his deathly-cool Ferrari Testarossa.

I don’t mean at all to detract from the efforts of Zane Lowe and the artists he brilliantly assembled for work on this project; it is never anything but inspiring to see so many creative minds pitch in on the same idea without the incentive of profit. But the truth is that Drive is a truly special achievement in film scoring and soundtracking, and no matter the talent of the writers and performers enlisted by the BBC, this bold experiment was never going to match up to the era-defining original work. What it has done, though, is open up a delicious can of worms, insofar as it has stimulated debate on what exactly the potential for the remixing and rescoring of films is; I for one hope this is not the last time we see this sort of thing attempted, as it has only served to energise general interest in good music and good cinema. And that can never be a bad thing.

Header Image Source: Icon Films Distribution

Comments (1)

I totally agree that whilst it may not have worked this time, it was a great experiment and I hope to see similar attempts in the future!