Woody Allen: In Search of Lost Time

Woody Allen is at an age (78) at which he must know that he has seen more sunsets than he is going to see. A growing preoccupation with one’s past is not an unusual theme for an aging film director, and so it is perhaps not odd that two of his most recent films, Midnight in Paris (2011) and this year’s Magic in the Moonlight, are both set in the 1920s, a decade before he was born.

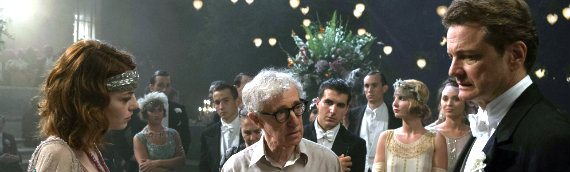

His unfortunately awful new film Magic in the Moonlight tells the story of a Chinese magician called Wei Ling Soo whose alter ego (or actual personality) is a pompous, rational and wonderfully stubborn Englishman called Stanley Crawford (Colin Firth, who carries the bulk of the film on his shoulders). There is talk of a new clairvoyant Sophie Baker (Emma Stone) who claims to have access to the ‘unseen world’ and Stanley is invited to come and help expose her as a fraud. She also claims to be able to contact dead relatives and displays a startling knowledge of the early lives of other characters. The most vivid scene is one particular moment involving a drowned uncle (“death by drowning”, she says to Firth’s character with a vacant, expressionless stare). Firth’s reaction has him wide-eyed and (momentarily) open mouthed, and manages to give some credence to the idea that the weight of the past can be gradually etched onto a face. It is just a shame that the often cringe-worthy screenplay takes advantage of the usual license for bad writing given to any film that manages to advertise itself as a rom-com.

I’ll now rewind to a much more accomplished film, Midnight in Paris. If I could choose a time and a place to live and breathe, 1920s Paris would not be far from the top of the list. In the film, a struggling writer called Gil Pender (Owen Wilson) has the enviable opportunity to do just that. During his wanderings around a smoke-filled and jazz-obsessed Paris, he meets the best of the talent that all converged in Paris at that one time: a delightfully overstated parody of Ernest Hemingway (“no subject is terrible if the story is true, if the prose is clean and honest, and if it affirms courage and grace under pressure”), a young F. Scott Fitzgerald (played by Tom Hiddlestone in a way that made me realise how strange it is to think that Fitzgerald must have, on occasion, been at least mildly sober) and an already famous Pablo Picasso. Salvador Dali, Gertrude Stein and Cole Porter also feature. A surprising and disappointing absence is the writer of Ulysses, James Joyce. Parisian lore tells the story of Joyce cowering behind his sturdier drinking partner after starting a fight, shouting “deal with him, Hemingway”. Eyewitnesses of this event surely died smiling in recollection.

Both films contain a reference to the twilight hours in their title, and it is not too much of a stretch to take from this the idea that Allen sees the night as having a deep kinship with our relationship with the past. It touches on the idea that our most active engagement with times gone by is in the dark, or, as darkness often suggests the absence of other people, when we are alone.

I hope I have set the scenes enough to point out that both films contain a reference to the twilight hours in their title, and it is not too much of a stretch to take from this the idea that Allen sees the night as having a deep kinship with our relationship with the past. It touches on the idea that our most active engagement with times gone by is in the dark, or, as darkness often suggests the absence of other people, when we are alone. As Allen, as with most human beings, gets older, his thoughts will inevitably begin to be directed more and more towards the past. Allen once famously quipped “in my next life I want to live my life backwards. You start out dead and get that out of the way”. It must be difficult for a film director entering his winter years to not use his work as an opportunity to explore and relive various moments in his life, and the constant reappearance in many of Allen’s films of certain stock characters (the neurotic, struggling artist; the neurotic, struggling love interest; the neurotic, struggling Jew. Clearly, Allen’s writing does a real service to both neuroticism and a healthy mix of associated struggles) suggests that a life already lived has a strong grip on his imagination.

The most amusing character in Midnight in Paris is the deceptively clueless Paul Bates (Martin Sheen), an educated idiot who makes a show of knowing a (very) little about everything. He has the telling habit of beginning every other sentence with the phrase “if I’m not mistaken”, and would perhaps on another occasion be seen unironically quoting Alexander Pope at the dinner table, declaring to everyone present that “a little learning is a dangerous thing”. However, Allen strangely gives him the dialogue that best defines the key notion of the film: “nostalgia is denial – denial of the painful present… the name for this denial is golden age thinking – the erroneous notion that a different time period is better than the one one’s living in – it’s a flaw in the romantic imagination of those people who find it difficult to cope with the present.”

That this completely rational view comes from the mouth of a charlatan suggests that Allen finds more comfort in the belief that acts and products of the imagination can at least attempt to disrupt the arrow of time, and reorient the bow from which it was fired. Another time, another place – go! Hemingway, it’s your round.

Comments