Ten years and it’s not Lost impact

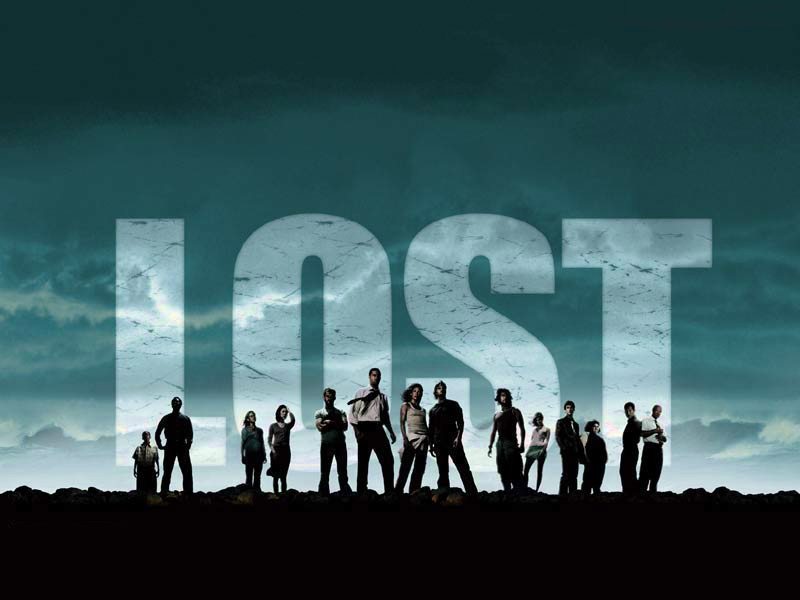

First airing on September 22nd 2004, Lost became a cultural phenomenon that none could have predicted. Launching countless water cooler discussions, the show was nothing if not divisive. When Lost finally revealed its hand at the end of its six-year run, many were left infuriated. Decrying its supposed lack of satisfying answers, they felt they had been sold one show, and given another. Lost’s heart always lay with its characters, but it had also sought to define itself through the mysteries that surrounded these castaways – a problem exacerbated by its showrunners and advertising in the media.

Despite the show’s mixed reception, few balked at its sheer ambition. As a network program that grounded itself in some very esoteric and metaphysical concepts, Lost was like little else before it. This ambition extended even into the practicalities of its filmmaking, with an opening episode that remains to this day quite possibly the most expensive pilot of all time at $14 million. Open to political discussion, it even chose to portray a former Iraqi Republican Guard and torturer in a sympathetic light as one of its central characters only a year after the advent of the Iraq War. The diverse nature of its cast was also showcased with the Korean couple of Sun and Jin, and in episodes that forsook the English language entirely, trusting its audience to rely on the subtitles provided. Clearly, the show had more in its arsenal than just a few magic tricks and sleight of hand.

Lost’s influence on the television landscape going forward would be wide and varied. Shows such as The Event and Flashforward came the closest to straightforward imitation, whilst simultaneously falling furthest off the mark. Building around a central mystery with character development playing a distant second, they failed to gain traction and were ultimately cancelled during their respective first seasons.

Hollywood wunderkind and Lost co-creator J. J. Abrams played his own part in launching various shows that attempted to recreate elements of the Lost formula. His earlier efforts saw greater success with Fringe and Person of Interest. Both shows built upwards from their typical network reliance on genre convention, broadly recognisable as procedural dramas from their emphasis on crime solving and standalone ‘mystery of the week’ episodes.

By building the character dynamics first, both shows were able to enact a deception upon the viewer as they slowly gave way to a more serialised form of narrative story telling. The wider mythologies of the respective shows grew. Fringe fully embraced its science-fiction leanings, much as Lost did in its latter seasons, whilst Person of Interest increasingly tapped into that same post 9/11 atmosphere that Lost was initially created under in order to realise its own intriguing web of conspiracy and shadowy power-plays. It was in this blending of genres that Lost found its greatest success, able to be whatever show it wanted through the simultaneous crutch and genius that was the flashback formula.

The show’s true spiritual successors would be found in more unusual places. In many ways, Netflix original Orange is the New Black has taken up the previous show’s high-concept approach to backstory, simply replacing one isolated setting for another in the form of the women’s prison. By refining the flashback formula, OITNB has similarly been able to deliver the unexpected for its audience without resorting to clumsy exposition. This is done in a way that elevates its characters, allowing pawns to become major players almost instantly through a greater understanding of their motivations and lives before incarceration, a tactic widely used throughout Lost’s own run.

Recently, HBO’s True Detective played with the Lost formula on a noticeably more meta-textual level. A crime drama built around the search for a serial killer known as ‘The Yellow King’, True Detective and its show creator Nic Pizzolatto delighted in teasing its audience with tantalizing clues that pointed towards something more pernicious at its center. From poster details to the colour of character’s costumes, grand theories arose on the Internet regarding uncanny forces at work in the show. With repeated references to supernatural tales and intimations towards Lovecraftian cosmic horror, the show purposely encouraged such speculations.

Clearly, the show had more in its arsenal than just a few magic tricks and sleight of hand.

It came as somewhat of a surprise then when the final act largely closed down on these more unusual ideas, choosing to end on the uplifting tale of what was essentially an unconventional love story between its two male leads. It felt like a meta-textual comment on a modern audience’s tendency to overthink their favourite television, and harkened back to the virtual communities that were created off the back of Lost, a show concurrent with the rise of social media. Above all else, it showed Lost’s continued influence even today, a ‘lightning in a bottle’ phenomenon that many have tried to emulate since.

Comments