The Umbrellas of Cherbourg at 50

The prestigious Cannes Film Festival has once again come to a close, leaving behind a sea of hype for films we’re unlikely to see until the final months of the year. I could deliberate on whether I think Jean-Luc Godard has finally realised some of the vast untapped potential of 3D technology, venture a guess as to whether Bennett Miller’s Foxcatcher deserves the Best Picture nomination it will so obviously receive or deliver a second-hand account of the alleged greatness of Mike Leigh’s Mr. Turner. Then again, I could mark this occasion with a friendly reminder that it was fifty years ago to the month that Jacques Demy’s landmark drama-with-a-melody, The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (or Les Parapluies de Cherbourg, if you prefer), took home the Grand Prix du Festival (1964’s equivalent of the Palme d’Or) on the festival’s 17th year. Call it a musical, call it an opera, hell, call it a postmodern horror film where time and circumstance stick a spiked brolly through youthful idealism if that’s really how you want to see it. In any case, it remains an enchanting, overwhelming work that deserves its place in the canon of French cinema.

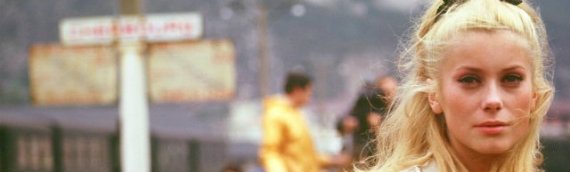

Had Jacques Demy quit directing after one film, he would still be remembered today solely on the merits of his brilliant feature-length debut, 1961’s Lola – a film he described as a ‘musical without music’, but his crowning achievement came three years later in the form of a movie where the music never stops. From a passing stranger asking for directions to a down-on-his-luck mechanic exclaiming profanity, no dialogue is too banal not to be sung. Arriving a year before a nuns-versus-Nazis musical became the highest-grossing film of all time, The Umbrellas of Cherbourg was abnormally focused on the ordinary. The film stars Catherine Deneuve as the sweet but naïve 17-year-old Geneviève Emery. Working for her nagging but well-intentioned mother at a struggling umbrella shop, she starts the film enamoured of the aforementioned mechanic, Guy Foucher (Nino Castelnuovo). Their bubble of self-contained bliss is suddenly popped when Guy receives a draft notice requesting his service in the Algerian War for two years. Geneviève vows to wait for Guy’s return but pressing financial problems and an unplanned pregnancy put her commitment to the test.

We all have ideas of how this is supposed to play out. Hopefully Geneviève remains loyal to her one true love through all her hardships and the two tearfully reunite when Guy returns, or perhaps Guy is tragically killed in action and Geneviève is left grief-stricken and unable to love again. After all, this is movie love, the kind of love which is supposed to either break the stratosphere or shake the Earth as it hits the ground, a love which can be immune to the muddying effects of time because it is confined to 90 minutes of screen life. When Geneviève looks directly into the camera through tearful eyes to say “Never will I forget him”, it feels like a promise to honour our preconceptions of great screen romances. But Demy recognises that, as much as it may upset our inner adolescent, even the most intense of feelings can be just fleeting emotions which degrade with the passing of time. Devotion gives way to compromise and the passion which once felt all-encompassing is confined to a painful but fading memory. When Marc Michel’s successful jeweller Roland Cassard (a character Demy first introduced in Lola) announces his desire to marry Geneviève, he comes across less as an obligatory competitor to Guy and more as Geneviève’s saviour by default. It’s an acknowledgement of the nuances in life which most films of any genre actively try to avoid. “People only die of love in movies”, Madame Emery reassures her daughter. The sentiment is both comforting and heartbreaking. It’s fittingly harsh that by the third and final part, ‘the return’, the film’s quaint titular umbrella shop has ceased to be, never to return again.

That being said, for all the film’s self-awareness and biting honesty, this can hardly be considered a work of cynicism. Demy was too much of a romantic to borrow components from the Hollywood musical purely to deconstruct them (we already had Godard’s Une femme est une femme for that). The film’s down-to-earth story is knowingly at odds with genre convention and there are certainly instances of self-aware humour (a co-worker of Guy who prefers film to opera tunefully remarks, “All that singing gives me a pain”) but Michel Legrand’s captivating, bittersweet arrangements are also sincerely, reverently in step with the romance and sorrow of the two leads. Despite the absence of any obvious musical ‘numbers’ for first time viewers to latch onto, these are melodies which elevate everyday drama to something fantastical. The dazzling candy-coloured visuals further evoke this impression of real life filtered through fairy tale in a way which can be both gut-wrenching and euphoric, with a sense of irony which enhances rather than undermines these feelings. The eccentric décor and lively apparel is a treat on the most basic of aesthetic levels (Wes Anderson was certainly paying attention) but it’s also a clever work of character-based colour coding (blue is strongly associated with Guy, Roland has black…) and sly foreshadowing (the parade of bright umbrellas in the opening credits ends with a funereal row of blacks).

“People only die of love in movies”, Madame Emery reassures her daughter. The sentiment is both comforting and heartbreaking. It’s fittingly harsh that by the third and final part, ‘the return’, the film’s quaint titular umbrella shop has ceased to be, never to return again.

And of course, riding the wave of this fantasy is the irreplaceable Catherine Deneuve, in the role which would prove to be her breakthrough. Only 19 years old at the time, her animated performance is the physical embodiment of Legrand’s score. Even at Geneviève’s most self-centred, she never fails to win our affections because Deneuve’s considerable charm is implicitly linked with her sheltered character’s initial fragility. We see the commotion in her as she tries to come to terms with the revelation that life and love are not as straightforward as she once thought and we see the inner strength she finds to pragmatically adjust. With her effortless radiance and a beyond-her-years grasp of a range of both stifled and exposed emotional extremes, it’s easy to see how she’s found work since in some of the best films of many a celebrated director, from Roman Polanski and Luis Bunuel to Arnaud Desplechin and Lars Von Trier.

Like Demy’s film, Von Trier’s Dancer in the Dark is a devastating deviation from the norms set by the American musical but a key difference between these two works is that Von Trier’s subversive, horrifying drama is more concerned with tearing down old traditions than giving the form new life. To put it another way, Von Trier is primarily destructive where Demy prioritises creation. It’s the difference between a cinematic terrorist and a cinematic freedom fighter. Demy expanded the role of music in cinema beyond the boundaries set by Hollywood to create a work of unprecedented maturity and emotional complexity without dispelling the otherworldly exuberance which draws people to musical films in the first place. Fifty years on and The Umbrellas of Cherbourg still feels like a universal truth told with all the sweetness of the biggest lies.

(Header Image Source, Image 1, Image 2, Image 3)

Comments