Never judge a book by it’s cover, right?

The Post-Birthday World

By Karishma Jobanputra

The well known saying that we should never judge a book by its cover is often repeated. If you judge a book by it’s cover you are shallow, superficial and above all, wrong. Yet, whether or not we want to admit it, we do judge books by their covers. Why? Because it’s human nature. When you meet someone for the first time, it’s said that we form an impression of them in just seven seconds. In the time it takes to pick up a book in the bookshop you can certainly scrutinise the front cover, and will either put the book down or read the blurb and first page. You make the initial decision based on the cover. With this being the brutal reality, it is more important than ever for authors to make sure they get it right. Unfortunately, it seems Lionel Shriver, winner of the Orange Prize for We Need to Talk About Kevin, has got it wrong with her eighth novel, published in 2007, The Post-Birthday World.

Whilst there are several covers, the one which I have come across most features a cupcake case and wedding ring. The cover seems to be an attempt at minimalism, remaining alluring without giving too much away. Unfortunately, whilst it does hint that the book is about relationships, it has been given the “chick lit” treatment. The cake and the ring point to a book about another broken heart, in which the female character finds solace in a cupcake and eventually marries the prince (not that there’s anything wrong with these books). It’s simply that this book is so much more and it’s a shame that, in this case, less is not more.

Whilst there are several covers, the one which I have come across most features a cupcake case and wedding ring. The cover seems to be an attempt at minimalism, remaining alluring without giving too much away. Unfortunately, whilst it does hint that the book is about relationships, it has been given the “chick lit” treatment. The cake and the ring point to a book about another broken heart, in which the female character finds solace in a cupcake and eventually marries the prince (not that there’s anything wrong with these books). It’s simply that this book is so much more and it’s a shame that, in this case, less is not more.

There are also many different views on how the author’s gender affects the book cover and which readers it will appeal to. Here, Lionel Shriver is a more masculine name and yet the book has not escaped a “chick lit” makeover, confusing everyone; is this a romance novel written by a male (unconventional), or a book about relationships with an abominable cover? There’s no way to know in those seven seconds in the bookshop and so it’s easier to put the novel down and pick up another.

The cover fails to convey the real nature of the story and brilliance of the dual narrative. Shriver has once again created an addictive story, compelling characters and a twist with the parallel-universe structure of the novel. But the cover does not do justice to the story. However, I invite you to ignore the cover and delve into the novel…you won’t be disappointed with the content, that much is certain.

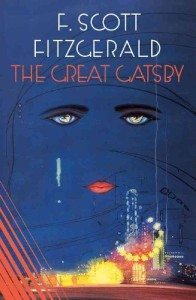

The Great Gatsby

by Helena Skinner

The universally recognizable cover art for The Great Gatsby is enduring and iconic in its ambiguous design. The staple wall art of any student hungering for an effortlessly affected air, this is the “Great Book cover” for the “Great American Novel”, yet discussion can be asked about Fitzgerald’s later disenchantment as a novelist.

The “Celestial Eyes”, as entitled by artist Francis Cugat, was designed before the manuscript was completed. Famously Fitzgerald wrote to his Editor requesting the art be reserved for his work, he pleaded he had already ‘written it into the book’. Although it is uncertain who the striking imagery of ethereal and mystical eyes was first conceived by, Cugat and Fitzgerald are as inextricably tangled in its inception as the art and the novel themselves.

The “Celestial Eyes”, as entitled by artist Francis Cugat, was designed before the manuscript was completed. Famously Fitzgerald wrote to his Editor requesting the art be reserved for his work, he pleaded he had already ‘written it into the book’. Although it is uncertain who the striking imagery of ethereal and mystical eyes was first conceived by, Cugat and Fitzgerald are as inextricably tangled in its inception as the art and the novel themselves.

Often employed by teachers to consolidate the themes of the text, the cover ambiguously connotes sorrow and excess. It’s immediate and most common association is with the eyes of T J Eckleburg, the moral arbiter who observes the corruptions and decadence of a disillusioned generation from the peeling billboard in the Valley of Ashes. Or indeed the dislocated eyes and mouth perhaps belong to Daisy Fay, described by Nick Carraway as a ‘girl whose disembodied face floated along the dark cornices and blinding signs’.

It is these ‘signs’ and symbols that are succinctly suggested by the cover. The meaning instilled in objects and places by the characters throughout The Great Gatsby resonated with the American propensity for creating meaningful symbols. Nick realizes this symbolism constitutes a central component of the American dream; the promise of the ‘orgiastic future’ is encapsulated for Gatsby in the green light – the investment of hope in this ‘sign’, being identical to how the first settlers impregnated their new nation with values and ambition. The cover, with its abstracted facial features and ethereal light serve as a reminder of how signs are devoid of any meaning save that which we give them. TJ Eckleburg’s faded eyes symbolise the demise of the American dream.

Parallels between Gatsby and his author are often drawn. In one of Fitzgerald’s final interviews he ruminates on writing; ‘a writer like me must have an utter confidence, an utter faith in his star’, yet he goes on to say ‘Ernest Hemingway has it. I once had it…something happened to that sense of immunity. I lost my grip’. It is hard to resist comparing his eventual self-disillusionment with the demise of the American dream and its meaning mourned in The Great Gatsby. Interestingly Hemingway writes of an encounter with Fitzgerald in A Moveable Feast. Hemingway despised The Great Gatsby’s ‘garish’ cover noting he ‘took it off to read’, yet he records how Fitzgerald ‘said he had liked the jacket and now he didn’t like it’. Possibly this explains the cover’s popularity amongst egotistical adolescents, indulgently sanguine, void of Fitzgerald’s eventual world weariness.

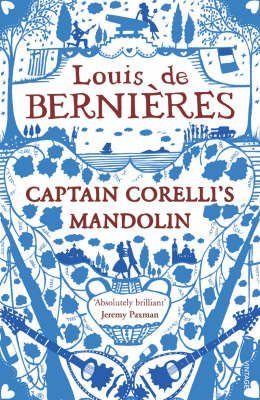

Captain Corelli’s Mandolin

by Sandeep Purewal

Captain Corelli’s Mandolin is, admittedly, one of my favourite novels. True love overcoming obstacles in the face of war is the perfect formula for any romance, and Louis de Bernières’s novel hits the nail on the head. The novel tells the story of Pelagia, a young girl who lives on the Greek island of Cephallonia and falls in love with Corelli, a soldier in the Italian occupying forces.

But I am not writing a piece on how much I love the novel. Rather, I am writing this to tell you why I think that the cover of the novel is one of the best that I’ve seen.

The cover accurately displays the juxtaposition between love and war which is so delicately portrayed in the novel. For instance, at the top of the cover is an illustration of a girl, presumably Pelagia, holding a flower and sitting on a canon. Next to her, Corelli plays his Mandolin, dressed in his military uniform. This represents the conflict of emotions that Pelagia is forced to struggle with; she loves Corelli deeply, however must acknowledge the fact that he is ‘the enemy’. This dark contrast is echoed by the fact that towards the bottom of the cover, we see blue rifles covered by purple mandolins, the mandolins being what Corelli uses to express his eternal love for Pelagia.

The cover accurately displays the juxtaposition between love and war which is so delicately portrayed in the novel. For instance, at the top of the cover is an illustration of a girl, presumably Pelagia, holding a flower and sitting on a canon. Next to her, Corelli plays his Mandolin, dressed in his military uniform. This represents the conflict of emotions that Pelagia is forced to struggle with; she loves Corelli deeply, however must acknowledge the fact that he is ‘the enemy’. This dark contrast is echoed by the fact that towards the bottom of the cover, we see blue rifles covered by purple mandolins, the mandolins being what Corelli uses to express his eternal love for Pelagia.

In the middle of the cover is a boat on a river. To the left of this boat is a man playing a mandolin and to the right is a group of soldiers standing next to a tank. The boat seems to be symbolic of Corelli and how he struggles with getting to grips with the two sides of him. He loves Pelagia and he loves music, however he cannot forget that he is an Italian soldier.

One of the reasons that I loved the novel when I first read it was how it consisted of many small stories interwoven together. The beautiful cover of the novel certainly encompasses this. Among the delicate floral patterns are images which remind us of various scenes in the novel; the churches, the bottles of wine, the flags and the characters.

They say that you shouldn’t judge a book by its cover, but in this instance I recommend that you do. I implore you to pick up a copy of Captain Corelli’s Mandolin and escape to the mystical island of Cephallonia.

Which Picture of Dorian Gray?

by Carmella Lowkis

When a protagonist is so good-looking that he trades his soul for eternal beauty, you would think that the book’s cover might be equally concerned with appearances. The first time that I read Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, it was the 2003 Penguin Classics edition, fronted (somewhat predictably) with a picture of Dorian Gray. However, this pompous-looking youth, with his bad haircut and ruddy face, seemed impossible to reconcile with the man “of ivory and rose-leaves” described by Wilde. The portrait simply wasn’t attractive enough!

The error committed here is hardly isolated – numerous editions sport an illustration of a man who, while not being ugly, is entirely mediocre. Why is this the case? Do the publishing industry operate on a different aesthetic plane to the rest of us?

Penguin’s 2009 edition, released to accompany a film adaptation of the novel, proves more successful with its image of Gray-as-portrayed-by-Ben-Barnes. Barnes is certainly more an “Adonis” than those men besmirching previous versions, but the cover still leaves much to be desired: a composition featuring Gray in the foreground, with Lord Wotton and Emily huddled behind him, is more suited to a Mills & Boon paperback than a work of classic literature.

Of course, beauty is a subjective concept, and so any attempt to illustrate Dorian Gray is going to prove challenging. Perhaps the solution is therefore to eschew an actual picture of Dorian Gray when publishing The Picture of Dorian Gray. I’ve noticed that some editions favour a photograph of Wilde himself, but the intention here is unclear. Are we supposed to picture Gray as looking like Wilde? It is true that critics are fond of drawing parallels between the shady character and his author, but I feel that this rather confuses matters.

Another popular solution has been a reversion to simple shapes or patterns, in lieu of illustration. I’m personally drawn to Random House’s 2008 edition, which boasts a purple cover with grey spirals; initially these seem abstract, but on closer inspection one can make out images: a scythe, a skull, a picture frame. It cleverly and tastefully represents the novel’s contents.

However, my favourite cover has to be that of the first edition book – minimalistic, beige, and with a charmingly simple gilt vignette and title. As the saying goes, ‘if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it’.

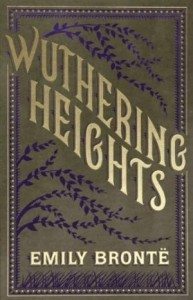

Wuthering Heights

By Anna Laycock

Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights has to be my favourite book of all time. I own three different copies of the novel, all with different covers. The first copy I came across was a 1995 Penguin Classics edition that was sitting unread on my mum’s bookshelf; the cover features a simple yet mysterious blue and grey watercolour painting of the Yorkshire moors. The second copy I received was a Bloomsbury Classics edition as a Christmas present when I was 14. This cover is bright orange and purple and features the image of a blue lightning strike. My last copy was a 21st birthday present and is a hard back Barnes and Noble Leather-bound edition; it is easily my favourite as with its golden lettering and satin ribbon bookmark, it is a beautiful addition to my bookshelf.

My three copies of Wuthering Heights all have distinctly different covers, and those are just a fraction of the many covers that have graced Wuthering Heights over the 165 years since it was published. As Wuthering Heights does not fit neatly into any genre of literature, the various different covers indicate what the publisher is trying to market the novel as. Some covers suggest it is a romance, others a gothic horror story, some highlight it to be a novel of manners and others do away with images, allowing only the title and the author’s name on the cover, emphasising the novel’s place as a classic of English Literature.

It is fascinating to look at how the covers of Wuthering Heights have altered as culture, fashion and literary criticism have changed across the decades. A 1944 copy gives the protagonists, Cathy and Heathcliff, a Hollywood makeover on the front cover. A blond haired Cathy with red lips and dark curly eyelashes cuddles into a tall, dark haired and handsome Heathcliff – an image very reminiscent of the 1943 Casablanca movie poster. In 2009, Wuthering Heights got caught up in the Twilight frenzy when a new edition was released with a Twilight-esque cover. The awful black cover featuring a white flower, the clichéd phrase “Love Never Dies” and a sticker labelling it “Edward and Bella’s favourite book” is clearly an attempt by the publisher (Harper Collins) to cash in on Twlight’s success by aiming Wuthering Heights at Bella Swan wannabes.

It is fascinating to look at how the covers of Wuthering Heights have altered as culture, fashion and literary criticism have changed across the decades. A 1944 copy gives the protagonists, Cathy and Heathcliff, a Hollywood makeover on the front cover. A blond haired Cathy with red lips and dark curly eyelashes cuddles into a tall, dark haired and handsome Heathcliff – an image very reminiscent of the 1943 Casablanca movie poster. In 2009, Wuthering Heights got caught up in the Twilight frenzy when a new edition was released with a Twilight-esque cover. The awful black cover featuring a white flower, the clichéd phrase “Love Never Dies” and a sticker labelling it “Edward and Bella’s favourite book” is clearly an attempt by the publisher (Harper Collins) to cash in on Twlight’s success by aiming Wuthering Heights at Bella Swan wannabes.

With all these various covers, we have to ask ourselves whether the cover of the book affects the way we read it. If it is marketed as a love story then are we more inclined to believe the relationship between Catherine and Heathcliff is based on love? Also, we could question whether the cover we choose says something about us. Perhaps our choice of cover highlights what we want the book to be about, be it a love story, gothic horror or a Victorian Twilight. Moreover as material objects, books have ornamental qualities. I for one want my copy of Wuthering Heights to be a gorgeous decoration on my bookshelf as well as an accessory whilst I read it sipping a cappuccino in Starbucks!

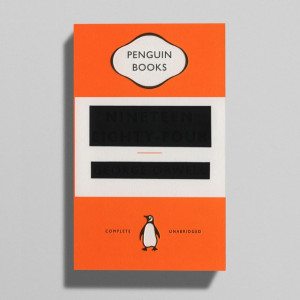

Best Book Covers: 2013 Penguin Classics print of George Orwell’s ‘1984’

by William Tucker

Such is the impact of Orwell’s seminal work, Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) that the adjective ‘Orwellian’ has come to mean any repressive tactic used by governments, an ironic twist given the novel’s bleak portrayal of an authoritarian dystopia.

There is not a design classic in the world of publishing to match the simplicity and accessibility of the Penguin Classic. Radical in its time for making books affordable and portable, in an era where huge, dusty tomes ruled the day, the debut of the classic orange three bands design in the 1930s brought high-quality literature to the masses.

Given the iconic status of these two institutions, it should not be surprising that the combination of the two is a triumph. But it says something about both Penguin and Orwell’s masterpiece that this cover still has the power to shock.

The title and author’s name are both blacked out in rigid censorship boxes, reminiscent of lead character Winston’s tenure at the euphemistically titled ‘Ministry of Truth’. To see this crude, unceremonious interruption of what is a design so familiar to us is deeply disturbing.

The title and author’s name are both blacked out in rigid censorship boxes, reminiscent of lead character Winston’s tenure at the euphemistically titled ‘Ministry of Truth’. To see this crude, unceremonious interruption of what is a design so familiar to us is deeply disturbing.

That Nineteen Eighty-Four has been re-published in this way could not be more important today. For a brief liberal moment at the end of the last century, with fascism and communism both vanquished, we could say that we had learnt the lessons of Orwell’s magnum opus. But the alarming slide towards authoritarianism seen in the west since 9/11, and the increasing preponderance of totalitarian China, makes Nineteen Eighty-Four more vital than ever.

Even given the return to detention without charge, extrajudicial execution, and warrantless surveillance, for some years the power of the internet gave hope that we might still be able to live in states that served us, and not the other way around. But the recent revelations that American and British security services have the capability to monitor everything about a citizen’s online lives should send us straight back to Orwell’s lucid, urgent prose.

‘Winston kept his back turned to the telescreen. It was safer, though, as he well knew, even a back can be revealing… The thing that he was about to do was to open a diary. In small clumsy letters he wrote: April 4th, 1984.’

Like Winston we cannot turn the telescreen off completely. With that in mind, this fantastic cover should help spread Orwell’s grim prophecy.

Comments