The forgotten victims of the Bangladesh factory collapse

In April, the world watched in horror as a factory in Bangladesh collapsed, killing an estimated 1,130 people, critically injuring thousands more and sending an entire nation into mourning. Outrage at the safety standards in place dominated the headlines and retailers rushed to sign new workplace standards pledges. For an entire month, people all over cheered every time a survivor was brought out of the rubble and donations to hospitals flooded in from the unlikeliest of places. Amidst the heartache, it really looked like steps were being taken so that this tragedy would be the last one in a country known for its cheap labour and its garments industry.

Six months later and life has moved on. Syria, US phone-tapping and Miley Cyrus are the big issues right now. Bangladesh is a thing of the past. But for Musamat Rebecca Khatun, that day at the Rana Plaza factory is still fresh. While her doctors and nurses were out celebrating Eid, she was lying in a hospital bed, one of her legs already amputated, the other getting infected. When her doctors returned after the festivities, they had to operate on her again. The shiny promises of a better future are lost on her. For Ms. Khatun, the only things that matter are her hospital bed, painkillers and an end to the cycle of eight operations she has already had to endure.

Srabon Ahmed Jehangir was a machine operator at Rana Plaza. He has fully recovered from his injuries and is fit to work again. Yet he is one of 1,400 survivors identified by the charity Action Aid who are unable to find a new job.

It might be tempting to classify Ms. Khatun as the anomaly, the survivor whose ongoing tragedy is terrible, but only because of her particularly depressing circumstances. Surely, the others better off, reaping benefits from the new and improved industry that has come about because their colleagues died without it? If only that were true. Srabon Ahmed Jehangir was a machine operator at Rana Plaza. He has fully recovered from his injuries and is fit to work again. Yet he is one of 1,400 survivors identified by the charity Action Aid who are unable to find a new job. This despite the fact that the garments industry remains the largest employer in Bangladesh and is currently in the middle of a period of growth.

Mr. Jehangir has said that some employers were unwilling to take him on because of his links with a national tragedy. These particular companies – who Mr. Jehangir refused to name as he is still trying to get a job with them – have not implemented any improved safety standards and are worried that international charities supporting the survivors will find out. Mr. Jehangir currently makes 3,000 Bangladeshi Taka a month (roughly £30), which is the same as his rent. He used to make 8,000 Taka; the difference of 5,000 has forced him to cut back on food and medication just so he can keep a roof over his head.

factories across the country continue unsafe practices, such as locking in workers during the day to prevent them from leaving early despite the risk of fires, using old fire extinguishers because they are cheaper, or penalising workers who approach journalists and charities with their stories.

Other survivors, like Ayesha Akhter, are suffering from a lack of proper post-surgical care. Ms. Akhter, all of nineteen years, has also fully recovered physically. But in a country where post-traumatic stress and depression are as alien as poor working conditions are here, she is unable to bring herself to go back to work. Worse still, she cannot explain why when her impoverished family asks. Instead of getting the emotional and psychological support that she needs, she is being pressured into earning money again. And for every day she is unable to do so, the stress at home becomes much worse.

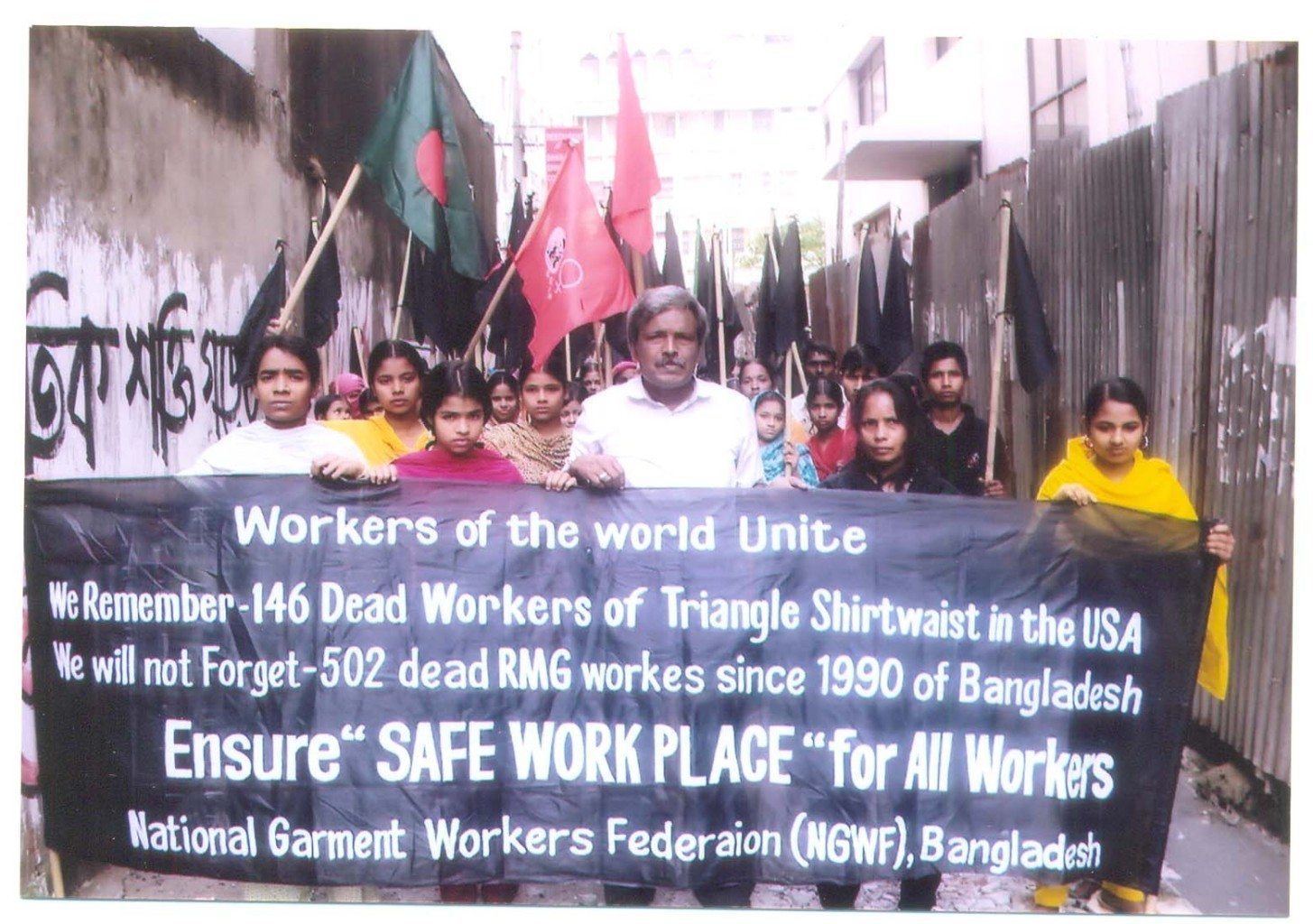

Ms. Khatun, Mr. Jehangir and Ms. Akhter are just three stories of heart-break that emerged from the rubble in April. Since then, workers have gone on strike several times to demand an end to the disasters that have plagued their industry for decades. H&M, Primark and Walmart have all lobbied for better standards, and have pledged compensation to the victims (largely unreceived). And all the while, factories across the country continue unsafe practices, such as locking in workers during the day to prevent them from leaving early despite the risk of fires, using old fire extinguishers because they are cheaper, or penalising workers who approach journalists and charities with their stories. Rana Plaza was the latest tragedy to hit Bangladesh’s garments sector. The way things are going, it is unlikely to be the last.

[divider]

Header image – flickr/dblackadder

Comments