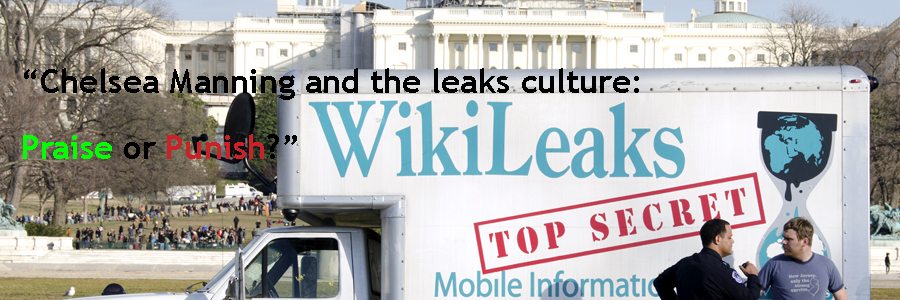

Tête à Tête: “Chelsea Manning and the leaks culture: Praise or Punish?”

Punish

This summer saw the conviction, on all but two counts, of former US private Chelsea Manning, for her decision to release thousands of classified American military documents to Julian Assange’s Wikileaks. Civil liberties’ groups and Manning’s assembled supporters have sought to portray her as a heroic individual, who stuck by her principles no matter the grave personal consequences.

This perception is profoundly wrong-headed. Although her defenders deny that there is concrete evidence of anyone having lost their lives due to the leaks, it is clear that they provided the Taliban with sensitive intelligence for them to use against the brave men and women who she had fought alongside.

Given that it was shown on 9/11 just how much devastation this cruel organisation can wreak when left unchecked, support for actions that make the War on Terror all the harder to prosecute seem incomprehensible.

Supporters of Manning – who are generally so quick to emphasise the sanctity of life when it comes to casualties of US foreign policy – would do well to remember the innate value of the lives that she, at the very minimum, imperilled. Indeed, rather than seeing the leaks as a courageous stand against a faceless military machine, it is important to consider the extreme risks to individual humans that they created, regardless of whether one agrees with the action in which they are engaged. Therefore, Manning’s behaviour must be considered deeply irresponsible on this level.

Attempts made to instead somehow romanticise Manning’s actions taps into the almost visceral resentment that some feel towards the American state. One can legitimately disapprove of some of the American tactics used throughout the War on Terror. However, the fact remains that the US is on the side of basic human rights in a continued global conflict against al-Qaeda, and America has the moral conviction and – as the sole superpower – the militaristic capability to contain and tackle.

Given that it was shown on 9/11 just how much devastation this cruel organisation can wreak when left unchecked, support for actions that make the War on Terror all the harder to prosecute seem incomprehensible.

If a culture of leaking sensitive intelligence ever took hold and drastically curtailed the War’s scope and effectiveness, then humans throughout the world, of all faiths and none, would see their most fundamental right – the right to live, rendered much less secure.

Those critics of the US who are lining up to support Chelsea Manning should thus consider whether they are acting in accordance with the notions of human rights and civil liberties which they appropriate. They are defending an individual whose actions endangered US service personnel and promoting behaviour wholly antithetical to stemming the inhuman terrorist menace.

[divider]

Praise

You may or may not have read in the news the revelations of mass surveillance undertaken by the American National Security Agency (NSA) and, completely unrelated to payments of £100m over three years, our very own GCHQ. Put simply, through the PRISM programme and others, these bodies have the power to find out pretty much anything you’you’ve been up to online – and these powers are not so much selective as a massive data-mining exercise.

Now, you can disagree with me about whether or not this is necessary. Many people think that, given the unpredictable, volatile world we live in the secret services need such powers to catch terrorists and criminals. Personally, I think the subversion of the concept of ‘innocent until proven guilty’ the revelations entail is a violation of our civil liberties.

By assuming everyone is a suspect until they are proven otherwise, and needing no warrant to see our online lives, the relationship between state and citizen is permanently damaged. But that’s not the point I’m making here.

One of the reasons defenders of PRISM and the like offer for why we shouldn’t worry about these programmes is that we live in a democracy. Therefore, goes the argument, governments won’t overstep the mark in the balance between security and liberty. This is a flawed premise, but does offer the best way to explain why this all matters.

As a citizen, we enter a contract with the state to a) keep us safe and b) protect our personal freedoms. We also give governments the right to do these things through popular votes. But if we don’t know what our governments are up to, how on earth can we pass judgement at the ballot box?

The self-defeating post-9/11 ‘nothing to fear, nothing to hide’ paranoia that has been used to stifle any debate about civil liberties […] is damaging our democracy.

The former NSA operative Edward Snowden blew the whistle on the massive and sweeping powers of the NSA and GCHQ – powers, like blanket logging of data that had previously been denied ever existed. Yet in order to make these revelations, Snowden had to flee to first Hong Kong and then Vladimir Putin’s Russia – hardly a place known for its democratic freedoms.

If it takes a 30-year-old computer technician to reveal the extent of the state’s power, then something has gone seriously wrong with democratic accountability. The self-defeating post-9/11 ‘nothing to fear, nothing to hide’ paranoia that has been used to stifle any debate about civil liberties, and brand Snowden a ‘traitor’ (as if al-Qaeda and their ilk didn’t suspect they were being spied on) is damaging our democracy.

I may be wrong. Governments may really need these powers. People may not care because they’re happy with the status quo. But please, let us have a debate.

[divider]

Header Image courtesy of Flickr.com/Chris Wieland

Comments