Books I Hate That Everyone Loves

10 Things I Hate About Holden – Jess Devine

[dropcap]N[/dropcap] ow, hate is a strong word and while there are many books I dislike, such as the Harry Potter series (I know – I’m a monster) there are very few that irritate me so much that I would confine them to room 101. However, there The Catcher in the Rye by J.D Salinger is one.

Many people may read this and just decide that I don’t ‘get it’; that I’m missing the spark of brilliance that has made the novel one of the most treasured books within contemporary American Literature. But there is just something about this novel that makes my blood boil. I can appreciate the fact that it was a breakthrough, an innovative voice of its time and that it helped pave the way for Young Adult fiction to be viewed in a more respectable light. Nevertheless, I can’t help feeling that I am reading the thoughts of an utter moron. I don’t have any sympathy for a privileged white male who, in my opinion, is moaning about how hard it is to be a privileged white male. My heart truly bleeds.

Many people may read this and just decide that I don’t ‘get it’; that I’m missing the spark of brilliance that has made the novel one of the most treasured books within contemporary American Literature. But there is just something about this novel that makes my blood boil. I can appreciate the fact that it was a breakthrough, an innovative voice of its time and that it helped pave the way for Young Adult fiction to be viewed in a more respectable light. Nevertheless, I can’t help feeling that I am reading the thoughts of an utter moron. I don’t have any sympathy for a privileged white male who, in my opinion, is moaning about how hard it is to be a privileged white male. My heart truly bleeds.

Maybe I’m just fed up with reading about angst-filled teens having an existential crisis. A friend said to me the other day that Catcher reminded her of The Bell Jar; I was outraged by this comment as Plath’s novel happens to be one of my favourites. It got me thinking, perhaps the reason I hate Salinger’s novel so much is because it didn’t do what I wanted it to – reading it as a fifteen year old I wanted to relate, to empathise but I didn’t. But Ester Greenwood’s feelings of apathy, listlessness and lost sense of purpose I could completely identify with as an eighteen year old.

So possibly I hate the novel not so much for what it is but for what it isn’t, or maybe I just hate it. I cannot deny it’s popularity and it’s influence within literature, and for that I am grateful. However, it has led to the publication of another novel I would gladly throw on a fire, that being Stephen Chbosky’s The Perks of being a Wallflower. I severely dislike this novel for many reasons, namely its constant reference to other ‘cool’ American novels and writers and it’s downright worship of Catcher which Charlie, the protagonist, is recommended by his English teacher. Firstly, I refuse to believe any fifteen year old American student had never heard of Salinger’s novel, but also I didn’t believe in Charlie. Much like I didn’t believe in Holden Caulfield.

I am possibly being unfair to these two well respected novels and I can see why people would like them, I just don’t. However, I think it’s a good sign if a novel can divide opinion and provide debate; it is not negative to be hated. What an author should really fear is not being thought about at all and Salinger’s novel will be talked about and read for many years to come, just probably not by me.

But we could always just put it down to me being a phony.

[divider]

The not-so-great Gatsby – Richard Brown

[dropcap]B[/dropcap] efore my vitriolic rant begins, a quick disclaimer: Fitzgerald is a stunningly talented writer. His prose some of the best I have ever read, especially in the party scenes, but a good set piece does not make a good novel.

[dropcap]B[/dropcap] efore my vitriolic rant begins, a quick disclaimer: Fitzgerald is a stunningly talented writer. His prose some of the best I have ever read, especially in the party scenes, but a good set piece does not make a good novel.

As an English Literature student, I love a bit of symbolism as much as the next man, but Fitzgerald takes it to punishing levels. EVERYTHING is a symbol, most of the time relating to the breakdown of the American Dream. Whether the symbols mean something or actually nothing isn’t particularly relevant. What is relevant however, is the sacrifice that Fitzgerald made in this pursuit. Any sense of depth of character is lost, along with the possibility of a morality that we can challenge, discuss and interpret rather than just accept.

There is nothing in The Great Gatsby to make the reader properly think or perhaps more importantly, care. We, like our narrator Nick, become passive. The characters themselves become little more than symbols, vacuous objects that it is, I would suggest, actively difficult to care about. Even the one driving force in the novel – the relationship between Gatsby and Daisy – where we would expect to see some investment in emotion, is cold, lacking, empty.

The Great Gatsby is not a bad book, but in the context of the reverence with which it is treated, it is hugely underwhelming. The language is beautiful, but it is missing any excitement, any vibrancy. As Ruth Hale said in a contemporary review in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, “Find me one chemical trace of magic, life, irony, romance or mysticism in all of The Great Gatsby and I will bind myself to read one Scott Fitzgerald book a week for the rest of my life.” I would make a similar promise, but I have some symbolism to decipher.

[divider]

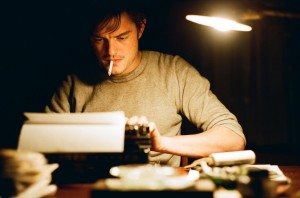

What Put Sam Steiner OFF the Road

[dropcap]T[/dropcap] ruman Capote said of Jack Kerouac’s most “seminal” work: “It’s not writing, it’s typing”. And, to Kerouac’s credit, he is a darn good typist. He typed out the whole of On The Road in less than three weeks on, if Wikipedia is to be believed, a single 120-foot roll of Teletype paper.

[dropcap]T[/dropcap] ruman Capote said of Jack Kerouac’s most “seminal” work: “It’s not writing, it’s typing”. And, to Kerouac’s credit, he is a darn good typist. He typed out the whole of On The Road in less than three weeks on, if Wikipedia is to be believed, a single 120-foot roll of Teletype paper.

But you already know this. Because it is this mythology of youthful spontaneity, rather than the text itself, that has given birth to the cult of On The Road. A cult founded on an infatuation with aching cigarette smoke, jazz music and quasi-bohemian New York pretentiousness that On The Road so handily impersonates. The truth is that the novel fulfills a fantasy. It’s a novel about a kid who really wants to be cool meeting a group of really cool kids who do nothing all day long except wax lyrically about how cool they are and how excited they are for the next stage in their cool lives. It’s an exercise in self-indulgence, yes, but the reason we still read it is because we’re fantastical about the setting. It’s the history and culture behind it that makes the book popular not its literary worth.

However, Catcher in The Rye and The Great Gatsby rank among my favourite novels, both of which share similar story aspects. And, to be less literary about it, The OC basically got me through my teenage years which, similarly, can be plotted as uncool people becoming cool and then rejoicing in their equally isolated coolness. This is not why I hated On The Road. I hated it because it was empty. The relationship between Sal and Dean could have been incredibly tender and interesting but instead it seems dull, unexamined and annoying. Similarly the treatment of women, other than being sexist, is devoid of any true meaning or emotional connection and thus elicits no emotional response. It’s typing not writing. Kerouac’s gone and had himself a great road trip and he’s decided to tell us about it in such a way that makes me wish so much that I was there if only to escape the mundanity of this recount.

[divider]

The Boy in the Striped Pajamas – Harley Ryley

[dropcap]T[/dropcap] he Boy in the Striped Pajamas was recently revealed as the most popular book for KS3 teachers to use in lessons on the Holocaust, both in Religious Studies and in History. It is a book that has been praised as the most honest and accessible book for young children to begin their education about the Holocaust. A book that has been lauded internationally for its excellent portrayal of the ignorance of many civilians as to what was going on. A book with one fatal flaw… it is built on a completely false concept.[pullquote style=”right” quote=”dark”]Historically, it sits in the ranks of the dubious historical fiction that seeks to shock or to entertain, not to offer truths[/pullquote]

The truth of the matter is that the whole premise upon which The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas is based is in itself a fallacy. There is no way that Bruno would have been able to ‘sneak’ into Auschwitz, as occurs in the book. For, if this 9-year-old boy could sneak in, why couldn’t other boys sneak out? The description of Auschwitz, as a wasteland and with its tin huts, is a description of Auschwitz-Birkenau. The commandant’s house, in which Bruno lives and which still stands today, is situated at Auschwitz I, a few miles away in the town of Oświęcim. Bruno would have had to walk a little further than to the bottom of his garden to reach Shmeul. Coupled with the sad truth that most children of a young age were sent to be exterminated upon arrival, the seemingly beautiful idea of “though lines divide us” would never, and could never happen. Historically, it sits in the ranks of the dubious historical fiction that seeks to shock or to entertain, not to offer truths.

I am not, however, criticising the way in which the book is written. On the contrary, I found the way in which John Boyne used Bruno’s misunderstanding of words, such as “Out-with” and “The Fury”, made this book one of the most uncomfortable reads I’ve ever experienced. So with this too to consider, what are we left with? A book that is beautiful, moving and almost entirely implausible. Undoubtedly, the innocence which is portrayed is heart-breaking, the fate of Bruno truly thought-provoking and the message poignant. Taken as a fictional representation of the horrors of the Holocaust, this book does its job impeccably. It is not, however, a history book. It should not be used to teach young people about the Holocaust, and it should not be praised as one of the most honest books about the Holocaust. There are so many memoirs, so many true stories of the Holocaust that are far more haunting than this one. And those stories are true. Why are we not teaching young people with these stories instead?

I am not, however, criticising the way in which the book is written. On the contrary, I found the way in which John Boyne used Bruno’s misunderstanding of words, such as “Out-with” and “The Fury”, made this book one of the most uncomfortable reads I’ve ever experienced. So with this too to consider, what are we left with? A book that is beautiful, moving and almost entirely implausible. Undoubtedly, the innocence which is portrayed is heart-breaking, the fate of Bruno truly thought-provoking and the message poignant. Taken as a fictional representation of the horrors of the Holocaust, this book does its job impeccably. It is not, however, a history book. It should not be used to teach young people about the Holocaust, and it should not be praised as one of the most honest books about the Holocaust. There are so many memoirs, so many true stories of the Holocaust that are far more haunting than this one. And those stories are true. Why are we not teaching young people with these stories instead?

[divider][message type=”custom” width=”100%” start_color=”#FFFCB5″ end_color=”#F4CBCB” border=”#BBBBBB” color=”#333333″]Tell us about books YOU love to hate @BoarBooks[/message]

Comments