Bioterrorism: How real is the threat?

Despite the threat of terrorism always hanging over the nation’s head, it’s not often that we hear of bioterrorism. Is this simply due to bioweaponry being far less prevalent than the traditional bombs or firearms, or could it be that we are worryingly uninformed about the matter?

The biological agents required for a bioterrorist attack are found naturally in the environment, and can be relatively easier to acquire than the agents needed for chemical or nuclear weapons. The bioterrorism risks of human and agricultural destruction are potentially threatening. These risks could be exacerbated by global terrorism, and also the ease with which biological agents can be acquired, weaponised and eventually used. Given the unpredictability of terrorism, should we question the commitments and costs to defence measures in the face of current governmental cuts? The threats posed by the use of bio-weaponry are not clearly understood by the general public and could potentially lead to fears of a bioterrorism attack.

In the history of biological warfare, no two nations have carried out such attacks on each other. Akin to the potential nuclear fallout between the United States and the Soviet Union during the Cold War, it was the possession of nuclear weapons more than their actual usage that carried any real significance. This is likely to remain so in the foreseeable future due to the fears of mutually assured destruction. As states have defined geographical territories, in addition to military and political establishments that enemies can physically retaliate against, it is often argued that any present-day threat of biological warfare would almost certainly involve the role of terrorists. Some suggest that the pursuance of bioterrorism is now inevitable – Is this the case?

But just how easy is it?

Because terrorists traditionally lack the logistical and technical sophistication required for biological warfare, bio-weaponry could continue to remain far from their reach.

Assuming success in acquiring the biological agents, the complexities of science could hinder the subsequent weaponisation of these agents. The cultivation and production of weapons-grade toxins or spores, and the successful aerosolization – converting a physical substance in to a gas – of these particles, would involve highly-specific laboratory conditions, knowledge and skills. For example, the bacteria Francisella tularensis is a potential agent of bioterrorism, and is extremely difficult to cultivate in laboratories. In addition to this, the accumulation of large quantities necessary for a bioterrorism event would prove difficult for terrorists with presumably less resources and expertise.

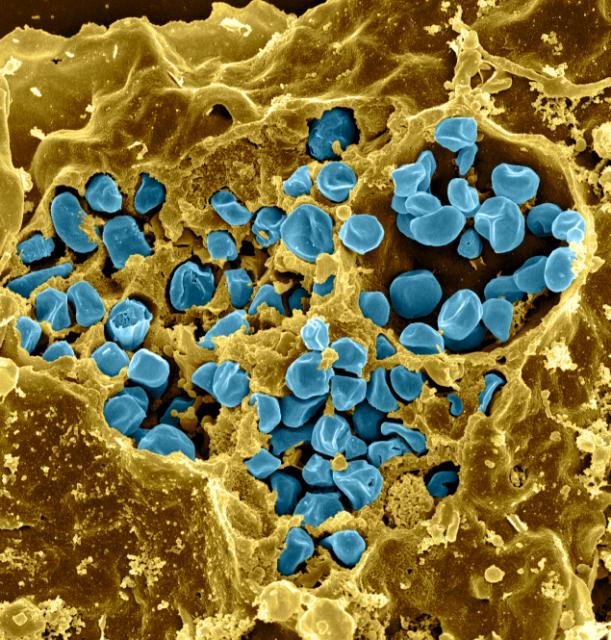

Biological agents are also living organisms. Unlike chemical or nuclear materials, the maintenance of viable stocks requires scientific expertise and years of experience. A series of attacks on several news media offices and U.S Senators occurred in 2001, where anthrax spores (the spores of a lethal disease) were contained in letters mailed to the victims, resulting in 5 deaths. The samples used in the 2001 Anthrax attacks were found to originate from state-sanctioned research conducted by Dr. Bruce E. Ivins; a leading figure in anthrax cultivation at the United States Army Medical Research Institute for Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID) with over 20 years of experience. The achievement of such high technical standards is likely to remain beyond an individual without sufficient expertise and laboratory resources.

Finally, the process of dissemination – the dispersion of the bio-weaponry – exposes biological agents to harsh environmental stresses, reducing its viability as infectious particles. Solar degradation, atmospheric dispersion and aerosolization stress can all affect the success of a bioterrorist attack.

Given the multitude of obstacles that stand in the way of bioterrorism, it is no secret that the use of firearms in the course of terrorism is considerably simpler, yet no less lethal.

While science may constitute the first layer of defence, many are concerned with the possibility of rogue scientists or the recruitment of scientifically qualified members by terror organizations. For example, at least three of the 9/11 hijackers were sent for flight training in preparation for their mission; an evidence of the commitment and determination some groups may possess.

Can we justify governmental spending to defend us against bioterrorism? Whilst non-state actors may lack in scientific sophistication, even the most rudimentary or crude methods of weaponry may be sufficient for a ‘successful’ terrorist attack. Much of the above evidence contests the idea of bioterrorism being a legitimate threat, and most would hope to never have to reap the payouts of such investments, but it could be essential for the preservation of national security.

Comments