Denis Avey: To believe, or not to believe?

Few historical accounts evoke emotion like the Holocaust, and few expeditions epitomise the true meaning of the word ‘bravery’ like swapping uniforms with a Jewish inmate to break into Auschwitz.

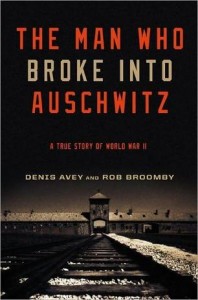

Denis Avey, a veteran of World War II, claimed to do this in his moving memoir, The Man Who Broke Into Auschwitz (2011), which I have immersed myself in over the Easter holiday. When discovering that the integrity and accuracy of the account has been questioned by a number of publications, I felt robbed and cheated. Surely this masterpiece is not a cynical act of exaggeration?

Co-written by Rob Broomby, a journalist at the BBC, Avey writes of his experiences in the war; the hunger, pain, omnipresent fear of death and the thriftiness required to survive. It is thrillingly written, and done so with the clarity and poignancy of a man who waited 62 years to reveal the full account of his experience, after first being approached by American prosecutors in 1947. But the book, as suggested by its title, revolves around Avey’s astonishing break-in to Auschwitz III.

An obvious question is to ask why Avey only told his story in 2009. The man himself claims that authorities simply were not interested in hearing about his ordeal; instead, he became acclimatised to bottling up his emotions, channelling them through pernicious means. Avey describes screaming in the middle of the night alongside his first wife Irene, even throttling her in unmitigated terror at one point, as memories haunted him. Reticence is entirely understandable if he did indeed experience the horrors of a Nazi concentration camp.

The word ‘if’, though, is hugely problematic. Avey first spoke to the Imperial War Museum on July 16, 2001, where he talked for five hours about his nightmares and the psychological and physical turmoil suffered in war: yet he did not mention the swap. In September 2004 and January 2005, Avey was interviewed by the journalist and documentary writer Diarmuid Jeffreys for his publication Hell’s Cartel; he mentioned losing an eye after being whipped with a pistol by an officer, but once again neglected to discuss Auschwitz. Broomby himself has sought to shield Avey from censure, reminding critics of his Post Traumatic Stress Disorder in the aftermath of the war. So why, then, was he able to talk about so many aspects of the war before meeting Broomby?

Avey was unquestionably a good and brave man, but accounts of historical atrocities such as Auschwitz must be accurate like any non-fiction. Unfortunately, since the publication of the book, a wide variety of esteemed figures have questioned the accuracy of it. In The Man Who Broke Into Auschwitz, Avey states that he swapped uniforms with a Dutch prisoner called Hans and smuggled himself into Auschwitz III. However, in a talk to Oxford students before the book was published, Avey claimed that he in fact swapped places with Ernst Lobethal in Auschwitz II, a man with whom he had a close friendship and spent years trying to track down through his sister, Suzanne. Unfortunately, try as we might to defend Avey, solving this historical contradiction is pivotal in recognising the book as authoritative.

Survivors from camp E715, the camp next door to where Avey was held as a prisoner of war (PoW), also dispute Avey’s account. Brian Bishop, 91, insists that there is no chance Avey simply swapped places with Hans (or Ernst?): “To do something like that you need to have several people helping on both sides – our side and the Jewish side”. Even the daughter of Ernst Lobethal, Ingrid Lobet, dismisses claims that Avey swapped. Suddenly Avey’s vivid account of seeing a corpse hanging from a gibbet and feasting on potato peelings for breakfast could be interpreted as an insult to those who truly experienced Auschwitz and, indeed, died there.

Quite simply, it is easier not to believe Avey. Auschwitz historians and survivors have been queuing up to question his account, and even co-writer Broomby himself admitted that “he could not verify the account; I just know what Denis is like by looking into his eyes”. Unfortunately, doubts will plague this best-selling, beautifully-written account of a World War II survivor – published in ten countries – because of the lack of evidence. Avey himself was stunned by the reception, stating that “I can’t really believe that people would believe what I did”, and it now seems that people don’t.

I really want to believe the 92-year-old Denis Avey, a braver man than I ever will be. In reality, I wish that I had never read sceptical reviews and that I remained in unassailable awe. But we will never know for sure that it is a truthful account, and for this reason, it cannot be read as a historical publication.

Comments (5)

I remarked to my wife while reading Avey’s book, “This is awfully hard to believe.” Now I see many others are skeptical too. None of us have any way of confirming his story or refuting it. I too developed a negative opinion of Avey, believing him to be a braggart and bully in his younger days, and even later in his life. But I just don’t know.

Definately not. I quit reading the book even before I got to Auschwitz. All he did was brag about how smart he was,how he won every fight, before and during war. I thought it was the ravings of an elderly man. Just my opinion.

I’m not sure it matters if he made the swap, or not. The account of his war, imprisonment, I G Faben, and surviving the final death march is all pretty much verified, or verifiable. I must admit that the return of the lucky recipient of his generous swap. twice, did stretch my credulity, but the account as a whole and the very moving testimony of the survivors is, I think, significantly more than enough justification for the writing of this excellent and amazing book. I am saddened by just how quickly the critics moved and sincerely hope that their words did not significantly upset this brave and talented author in the final years of his life. Shame on them.

I was working at Associated Dairies when Denis Ave joined us. (The company became Asda). It was in the late 1970s. I used to lunch with him in the staff dining room. He didn’t push his war stories, but reading the book I recognise some of them. Some perhaps aren’t in the book. I thought then it should be a book. There was another company employee, Ron Briar. Ron had been a POW in Nagasaki when the atom bomb came down by parachute. Ron and Denis didn’t know each other, as far as I know. Both their stories were incredible. Both said they didn’t think anybody believed them.

Please see Broomby’s acknowledgement of James Long who he says helped him ‘edit and structure the manuscript’. Long is an experienced novelist

http://www.amazon.co.uk/James-Long/e/B001HCU63Q and a staunch defender of Avey. It’s also worth studying the report of his 2005 interview with jane Kerr of the Daily Mirror

http://www.thefreelibrary.com/Brit+who+broke+IN+to+Auschwitz.-a0127524827 which states

“Posing as his friend Ernst, he watched women and children being marched into the gas chambers. I always wondered if they knew,” he says. “I hope not. You’d see them getting off the cattle trucks. They were told to strip and hand over all their clothes and go into the showers to wash. They were told they were getting ready to go to better camps. Except they weren’t those kind of showers. They were the gas chambers.”