Got neuroscience on the mind?

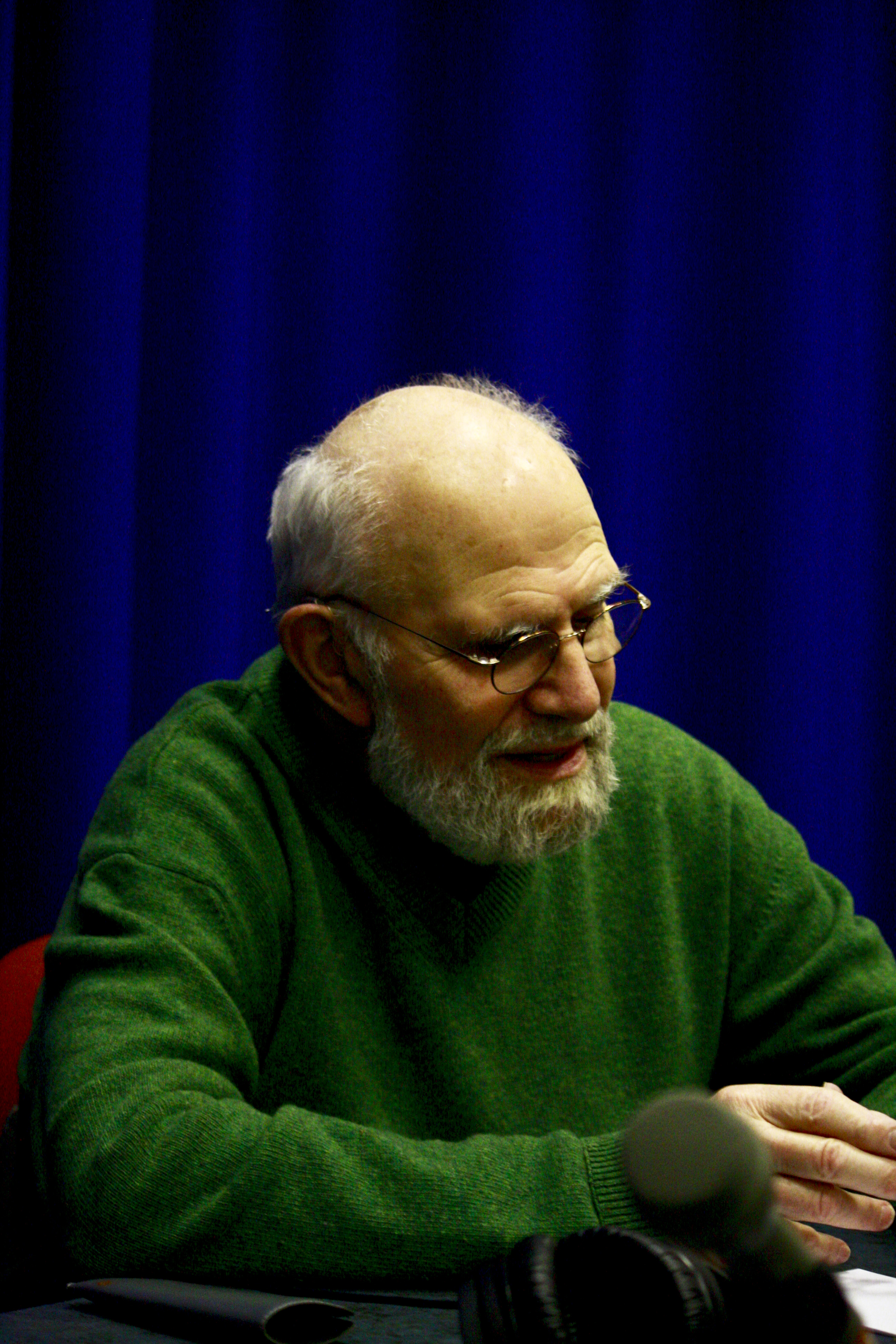

He’s written 12 best-selling books, inspired a play by Pinter, had his story adapted into an Oscar nominated film, has been awarded a CBE, and holds more honorary degrees and fellowships than I can count on the fingers of both of my hands – which is why I was surprised at how humane, gentle and warm Oliver Sacks was when I met him.

The world-renowned neurologist visited Warwick to give a lecture on the importance of case studies in medicine, which was the most attended lecture the university has held during its Distinguished Lecture Series, with around 1, 200 people in the audience. I was lucky enough to catch him for half an hour to talk about hallucinations, neurological advances and his love of swimming.

As a 79-year-old physician specialising in neurological deficits (such as a man who mistook his wife for a hat) Sacks is no stranger to physical impairments himself. He has prosopagnosia, which means that his ability to recognise people by their faces is impaired; a factor which he says has contributed to his shyness. He is also blind in his right eye, due to ocular cancer, and has tinnitus, a type of auditory hallucination in which one hears a constant ringing or hissing sound which may be intolerably loud. Despite this, Sacks seemed extraordinarily bright and on-the-ball, and answered my questions insightfully and intelligently.

I began by asking him what he was currently working on, and he told me that he was writing a book about memory, imagination and consciousness. Unlike much of his other work, though, many of the case studies in this book will be on historical figures that have not been his own patients – the likes of Romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, dramatist Brian Freel and the first deaf blind person to earn a degree Helen Keller. This excited me: Coleridge is my five-times great Uncle and I was fascinated to find out what Sacks knew about him.

I could not have anticipated such an answer – Coleridge, apparently was an accidental plagiarist! He suffered from cryptoamnesia, which is when one falsely thinks that someone elses material is their own. In his case, he incorporated lengthy passages originally written by German philosophers into his own work, believing he had generated such ideas. Helen Keller suffered from the same phenomenon, when as an 11-year-old child she wrote a book of delightful short stories that she believed had been a product of her own imagination. Unfortunately the stories turned out to be extremely similar to ones that had been published three years earlier, and she faced a barrage of abuse for being a ‘plagiarist’ and a ‘liar’.

We moved onto hallucinations. Regarding the most surprising illusions he has come across, he told me, “One can have hallucinations of their self, and see a mirror image of themself dressed the same way, mirroring their posture – it’s very peculiar.” Realising his own experiences with hallucinations, I timidly asked him if he had ever experienced such a phenomenon: “No, it’s something I have always hoped to experience, but never have…” was his enthusiastic answer. “I also hope to experience the so called ‘out of body’ hallucinations, where one is floating somewhere ‘up’ there and looks down to see oneself. Normally we feel that we are so firmly ‘in’ our own bodies, but in such an experience one feels vividly disembodied.”

He went on to enlighten me on the existence of dramatic ‘out of body’ and ‘near death’ hallucinations that can stimulate non-religious people to believe in an afterlife and become spiritual, chuckling that he would be extremely interested to know how such an experience would affect a “hard boiled atheist” like himself.

We then moved on to discuss Sacks’ proudest achievement – to which I received a startling, but humbling response. “I don’t feel proud of anything” he said, “The most I feel is not ashamed. If I can write anything that I’m not ashamed of, then I’m happy.” I assured him that he should feel proud of his work, and he revealed, “Well, the book that came from the deepest experience is Awakenings, but the one which I like the most is my Island book (The Island of the Colorblind), because it’s about travel, and exotic experiences. It has a license which none of my medical books have.”

We then conversed about Sacks’ own time as a student of Biology and Physiology at Oxford sixty years ago. The best thing about it was making new friends and experiencing new opportunities – “the world opening up in all sorts of ways”. He chose to specialise in neurology because he passionately believed that the brain was the most interesting thing in the universe, because it is essentially what makes every person who they are. Whilst psychology or psychiatry were alternative options, the physical basis of neurology was what appealed to him.

Undoubtedly, Sacks has been a huge inspiration to many scientists, both young and old, but who inspired him? A Russian neurologist called Luria, he told me, whose book about a man with a remarkable memory ‘The Mind of a Mnemonist’ he read as a medical student. It was only twenty pages into the book that he realised that it was a case history, rather than a novel, as he had assumed due to the inherent detail, beauty and drama presented on the pages. He was profoundly inspired, and has taken on the approach of describing the individual at the centre of a clinical story in his own writing

When I asked him what advice he would give for students wanting to get involved with neurology, he said, “Go for it! Fifty years ago I might have warned that it will not give one anything in the way of therapeutic satisfaction, as most neurological damage is irreversible and most neurological diseases are incurable, but that is less the case now.”

What has changed to make this possible? According to Sacks, vital technical discoveries like fMRI scanning and single unit recording (when the response of a single neuron is measured) which have allowed us to record activities in different areas of the brain and understand neural connectivity.

And where does he see neurology progressing in the next fifty years? Hopefully we will get a better idea of consciousness, he said; though some feel that such a finding will always be infinitely far away.

With the interview drawing to a close, I couldn’t resist asking Sacks about his passion for swimming. “Do you swim every day?” I asked. He told me yes: “I am clumsy on land and very much like to be in the water. I find in a long swim I can often get into a sort of trance-like, meditative state, which is pleasant.”

But for Sacks, neurology is always on his brain: “Sometimes when I’m swimming I start writing case histories in my head, and then I have to land at intervals and write them down.” I laughed, and told him I was going swimming that day. “As am I” he said, “I wear a green swim cap and fins – see you there.”

Comments