Dancing around Duchamp: The Bride and the Bachelors

Neither dead nor dull, this exhibition is alive. Layers of light, sound, dance, and visual arts intermingle and collide to create the mesmerising, multi-sensory Barbican exhibit The Bride and the Bachelors. Hanging glass installations allow you to peak through to dance sequences, or listen to the ghostly-mechanised piano performances and installation soundscapes. The constant jarring of sounds keep you ever transfixed: greedy to understand more. This exhibition wishes to not only present art; it hopes that each observer can begin to challenge the very definition of art itself.

Dancers perform Merce Cunningham choreography at The Bride and the Bachelors © Felix Clay 2013. Courtesy of Barbican Art Gallery.

Not content with a traditional gallery layout, French artist Phillipe Parreno orchestrated the mise en scène to mirror the absurdity, contradiction and tactility of all the pieces. Incorporating modes of temporal and spatial sequencing, Parreno brings a contemporary touch to the curation of these revolutionary avant-garde painters, artists, musicians and choreographers: Marcel Duchamp, John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns.

The French-born Duchamp was not embraced in America until the 1950s (when Cage, Cunningham, Rauschenberg and Johns were practicing) even though he had lived there for some time. The controversy about his early-twentieth century ready-mades seemed to clout the nation’s enthusiasm for claiming the New York residing artist for their own. His now infamous bicycle wheel on a kitchen stool caused mass hysteria in 1913 when it was deemed bizarre and without merit.

The concept of the ‘ready-made’ saturates the exhibition, which Duchamp’s most significant artistic invention, through which he elevated seemingly mundane, everyday objects to ‘art.’ Duchamp challenged the viewer to respond individually to the experience of the ordinary, to see art in the everyday and never be desensitised to the permanent aesthetic. This innovative demonstration of new art flowed between the collaborations of Duchamp and Cage, lingered with Rauschenberg, and was then reinvigorated with Cunningham and Johns. The artists exhibited conversed with each other both metaphorically and literally; Rauschenberg and Johns were in fact lovers for seven years after their fateful meeting in New York and the experimental musician John Cage and choreographer Merce Cunningham were lifelong partners.

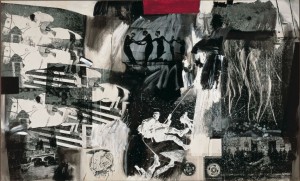

Robert Rauschenberg,

Express, 1963

Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, Spain © The Robert Rauschenberg Foundation. DACS, London/VAGA, New York 2013

On loan from the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the exhibition is named after the scandalous Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 (1912) and The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors (1923), which inspired Rauschenberg’s Express (1963), perhaps one of my favourite pieces. The then-new technique of oil on silk-screen canvas incorporates an almost frottage-esque layering of enlarged photographic images and serigraphy to create an explosively violent, cold and dynamic piece of startling complexity.

For me, Rauschenberg struck a chord between palpable honesty and nothingness, for it becomes clear as you mill round the gallery that these artists wish you to interact with the pieces, whether that be negatively or positively. They simply seek a response that reflects their position, which was outside of the American aesthetic. These works seek to be appreciated for their meaning rather than their beauty. Rauschenberg epitomises this belief: his work is not pretty but informative and enlightening.

Left haunted by Rauschenberg and Duchamp’s multimedia display, the bustling audience is free to wander the downstairs gallery where they can join Cunningham’s shadowy live performances. The sound of the soft patter of bouncing feet continues to echo across the main stage, enhancing the over-arching theme of motion.

These live performances are what I believe makes the exhibit quite magical. Arrive on a weekend and you’re guaranteed a live show to juxtapose your aesthetic experience, but arrive on a weekday and your mind is hoodwinked by Parreno’s layering of recorded soundscapes creating an effect of dancers pattering the floor. But the stage is empty, and so the perplexed viewer asks: how can we know the dancer from the dance? You sense that Cunningham in his original vision for this piece, and Parreno in reproducing it, both wished to amuse and shock, and this duality prevents the audience from being the cool surveyor – you are fully enveloped into their vision.

Rauschenberg declared he worked in ‘the gap between art and life’; Cage said that he wished to eradicate the difference between the two and Duchamp wished to turn his life into the very art that the Barbican unveils. Some view these artists, particularly Duchamp, as repugnant and pernicious – their impact on modern art being immeasurably damaging, but I believe this archaic view must be struck off. This group of men sought to encourage people to think again, independently and without judgement, to realise that art does not solely exist within beauty, but within the aesthetic – art exists within the everyday. I’m going to end with a cliché: ‘Beauty is in the eye of the beholder,’ but what if Duchamp is that beholder?

Comments