The academic rebrand of 2026: Constructive self-improvement or an unhealthy cycle of productivity?

As we counted down in anticipation, the dark sky of December 31 seemed to glow with the promises of the next year: 2026. It sounds futuristic, a year belonging to a faraway, high-tech multiverse. Having braved January, we are now living in its formidable modernity. People wait anxiously for the arrival of the new year, planning their resolutions with dedicated optimism. Yet the new year is less of a natural event and more of an invention of our own making. The concept of a year, defined by its glorious months, weeks, and days, is a mere social construct. Yes, the Earth orbits the Sun once every 365.24 days, but this is an astronomical fact – not a reason to buy another overpriced calendar. Though aliens might find our concept of a year fascinatingly meaningless, as humans, it has become a key marker for our personal and societal growth.

Our construction of time is nothing new. The Romans had their own annual calendar, the Julian calendar: every year, on January 1, they would honour the god of transitions and new beginnings, Janus. Today, the Western world’s calendar is much the same, the only difference being the Gregorian calendar’s omission of a leap day. While some people use this time to search for the best hangover cure, many students are focused on improving their academic productivity in 2026.

Many students see the new year as the perfect opportunity to ‘rebrand’ themselves academically; in other words, to boost their productivity and achieve the highest grades possible

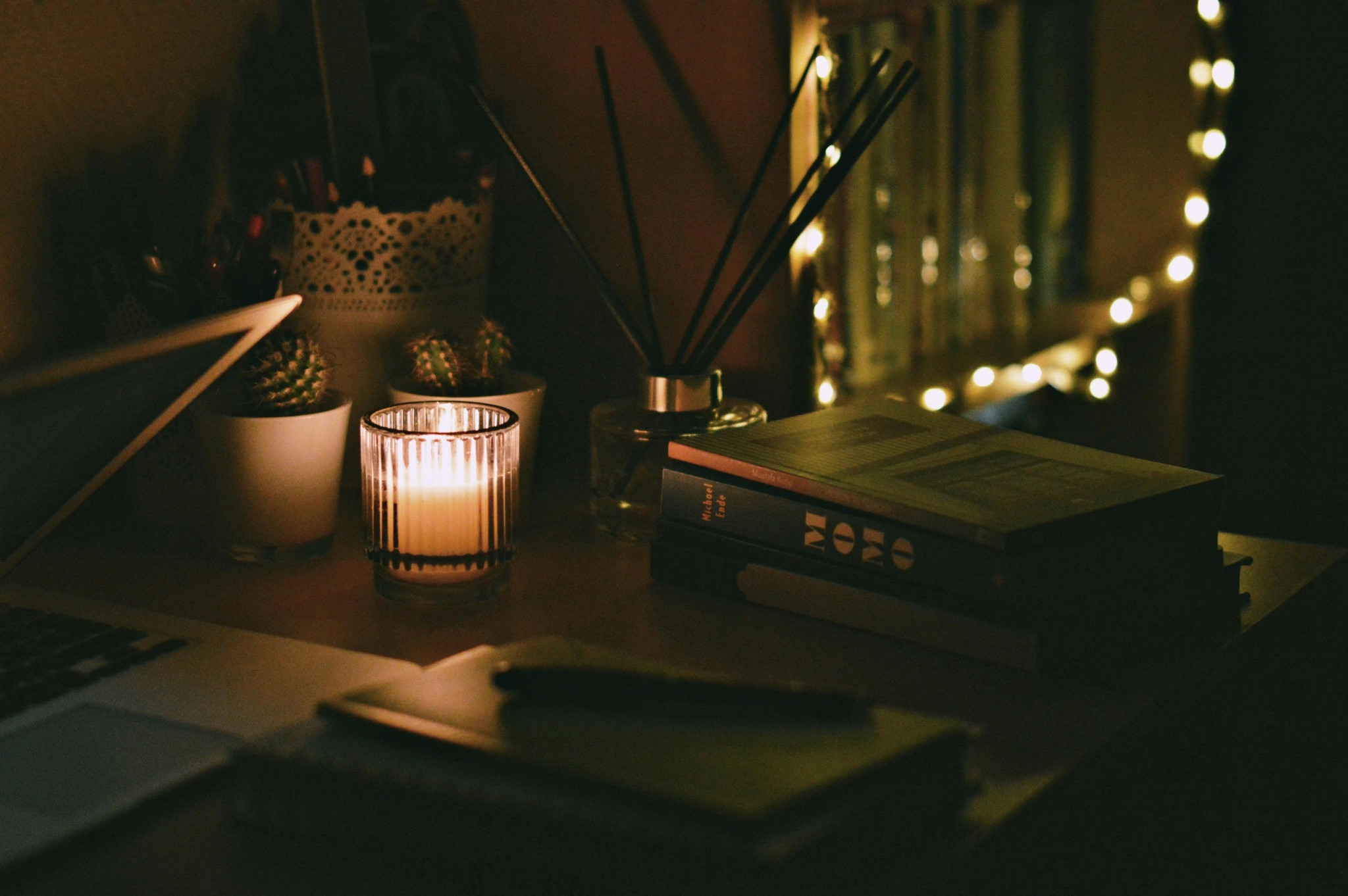

With the rise of ‘Study-Tok’ (TikTok videos that follow study routines or give academic advice), students are often made to feel that their academic effort is never enough. Videos promoting habits such as ‘studying until the candle burns out’ encourage excessively long study periods, upholding unrealistic standards of productivity. Many students see the new year as the perfect opportunity to ‘rebrand’ themselves academically; in other words, to boost their productivity and achieve the highest grades possible.

Issues arise when habits become all-consuming..

While this vision sounds appealing, its idealism fails to reflect the realities of student life. Refining your academic practices, such as studying more and improving your time management, are aspirational goals that may well lead to higher grades. Issues arise when habits become all-consuming. The new year often invites an unhealthy mindset surrounding productivity; specifically, the more you work, the better you work. Research suggests that while hard work is important, unhealthy hours of studying often lead to burnout and extreme stress. It has been reported that around 40% of students receive worse grades as a result of burnout, demonstrating its negative academic and personal consequences. Why does a fresh start introduced by the new year demand a growth in productivity?

The answer is… capitalism (is this the doomed answer to every question we have about our society now?). In the 1700s, as labour increasingly centred on manufactured goods and exports, the UK experienced the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. The historical epoch is characterised by poor pay for labourers tasked with working long hours in dangerous conditions. The longer you worked, the more you produced, and thus, the more you earned. Of course, labour conditions in the UK are almost unrecognisable today, with fairer wages and safer working conditions. There are strict rules governing workers’ rights surrounding hours, reflected by the ‘clock-in’ culture of the 9-5. Despite this, the enduring capitalist mentality that the more productive you are, the more successful you are, remains commonplace in and outside of the workplace. Employers reward those who stay beyond closing to finish tasks, and similarly, students are told that the more they study, the richer they will be later in life. Values that solely reward hard work and dismiss moderation and relaxation validate this capitalist mentality that sustains endless productivity.

Of the students polled, 75% claimed they often feel pressure to be more productive academically based on how much their peers studied. Indeed, as more people attend higher education, the stakes get higher.

As we enter 2026, many have established their own New Year’s resolutions. Many of these resolutions are inspiring, such as cutting down on alcohol or spending more time with family. Similarly, working harder and achieving more academically are also constructive goals. I like to use the new year as a chance to improve academic behaviours, such as reducing procrastination. To represent data on New Year’s resolutions, Crown Counselling conducted a poll to gather data on how students approach the new year, revealing that students are now more academically ambitious than ever before. Of the students polled, 75% claimed they often feel pressure to be more productive academically based on how much their peers studied. Indeed, as more people attend higher education, the stakes get higher. The competition is tighter, and students are working harder than ever. On one hand, this is a positive, boosting students’ motivation. On the other hand, it can be a toxic cycle that makes an individual feel that they are never doing enough.

The numbers don’t lie. In a survey conducted by The Boar, 63% of participants said they had a New Year’s resolution relating to increasing their academic productivity, such as improving time efficiency. During this time of year, people often engage with the mental marker, ‘new year, new me’. Many focus on how they can improve their lives with determination and consistency.

There is something desirable about committing to New Year’s resolutions. It is the rebrand manifested into action; optimism made a potential reality. There is nothing inherently wrong with New Year’s resolutions, and there is certainly nothing wrong with wanting to build better academic habits. I can’t help but wonder: how many of these academic resolutions are simply unhealthy productivity practices disguised as self-improvement?

Picture a hamster on a wheel. The hamster starts to run, its little legs jumping up and down, one and two, one and two, one and two… until it spins completely out of control in a dizzy exhaustion. This is academic burnout (minus the hamster’s cute fluffiness). Endless productivity, measuring your academic success by how often you work until the sun goes down, is far from fruitful. Despite the positivity that the new year can bring, it also ushers in unhealthy and unattainable resolutions. Much like a hamster wheel, the year is only a cycle. Have you really had time off over the term break, or have you just kept working as the hamster kept running? As the new year comes into full swing, let this act as a reminder to practise balance and moderation as well as dedication. Resolutions and rebrands are good opportunities to start afresh, but sometimes, the best thing to do is to simply do nothing.

Comments