How an army veteran from the West Midlands ended up on the streets of Gibraltar

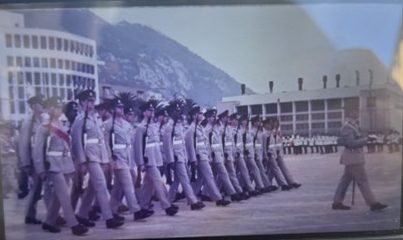

In the shadow of the Rock of Gibraltar, a British Overseas Territory better known for its monkeys and Mediterranean sun, a man from the West Midlands struggles financially, mentally, and physically. Peter Rogers, 63, originally from Rugeley, is a former British soldier who served the United Kingdom for a decade. Today, he lives on the streets of Gibraltar, an amputee punished by Gibraltar’s ID regulations that have left him abandoned by the system he once protected.

I met Peter in Gibraltar, sitting on the streets. Peter shared his tragic stories from the industrial decline of the 1970s Midlands to the streets of Gibraltar. I started by asking him why he originally joined the Army. He responded, “I come from a town in the West Midlands called Rugeley. Unfortunately, in the 1970s, when I was a teenager, the country was suffering from depression. The working week had been put down by the government to a three-day week … families were struggling, there was no work. It was suggested to me by my mum that I should think about joining the military. So I did at 16.”

To understand how Peter ended up in Gibraltar, one must look back to the economic climate of the 1970s. It was a period of industrial decline, and for many young men of that generation, the military offered a way out of economic stagnation in the West Midlands. This decline is rooted in the de-industrialisation that occurred as automotive companies began moving out of Coventry, leaving a huge gap in the labour market.

I was deployed to Northern Ireland in the 1980s, mostly dealing with riots, glass flying everywhere, petrol bombs.

– Peter Rogers

Peter went on to describe to me his experience of his service: “I served for 10 years. I was deployed to Northern Ireland in the 1980s, mostly dealing with riots, glass flying everywhere, petrol bombs. I did a year and a half, two tours of Northern Ireland, specifically Londonderry. My rank was a Private for those 10 years, serving in the Staffordshire Regiment.” These riots Peter was referring to were the 1997 Derry riots, which stemmed from Nationalist Catholics protesting against a march by the Protestant Apprentice Boys in Derry. Peter had to deal with hundreds of petrol bombs being thrown in his his direction, with the fire crew even called to de-escalate the situation.

After leaving the military, Peter eventually settled in Gibraltar, working in the security industry for 17 years. He contributed to society, paid his dues, and lived a normal life. That all changed three years ago in La Línea, just across the Spanish border. “I lost my leg after a motorcycle accident in La Línea almost three years ago. Subsequently, because I haven’t been able to get work and so haven’t been able to maintain the flat that I was renting, I lost the flat. I’ve had to sell everything I own to try and survive. Now I’m living on a bench.”

“You mentioned working in the security industry, what kind of work were you doing specifically” I asked. “I was a security supervisor at the airport for four and a half years. I was the guy standing next to an abandoned luggage in the middle of the airport while everyone else evacuated. After that, I was a security manager for 888 [a major gaming company] for six years, and then worked for OSG at the hospital. I’ve done my bit,” he replied.

The tragedy of Peter’s situation isn’t just his homelessness; it is the betrayal by his own nation after he has served it for a decade. Despite working in Gibraltar for nearly two decades, an expired ID card has locked him out of the welfare system. “With the care agency here, I’ve already spoken to government ministers, and nobody seems to want to help me. Even though I’ve worked here [Gibraltar] for 17 years, my ID card has expired, and they won’t renew it. They put a block on all ID cards because I’m not working and I don’t have a company paying my national insurance, so I’m not even allowed healthcare.”

I saw the health minister, and it’s been almost three months … They’re not doing anything in a hurry

– Peter Rogers

Even as a diabetic, Peter has still been unable to access medical care. “They keep saying you’re not registered, because my ID and medical card have expired. But they won’t renew it because I have no address. It’s a ‘Catch-22’. I saw the health minister, and it’s been almost three months. I’ve been waiting for them to make a decision on whether to send me back to the UK or help me here. They’re not doing anything in a hurry.”

Peter’s frustration is notable. He describes a sense of abandonment, particularly when he compares his treatment to that of others entering the territory. Gibraltar operates on a mandatory identification system for all residents aged 16 or over. The ID has multiple categories distinguished by the colour of the identification card. The Red Card is for Gibraltarian citizens; on the other hand, the Magenta Card is for residents from the mainland UK post Brexit.

They’re just leaving me, a 63-year-old man with a leg missing, out on the street.

– Peter Rogers

Individuals who established residency in Gibraltar before Brexit, like Peter, are issued the Blue Card. Blue Card carriers are required to provide proof of address when renewing the residency card in Gibraltar. As Peter was unable to continue paying his rent after losing his job following the loss of his leg in the motorcycle accident, he was unable to renew his residency card in Gibraltar, leaving him even more helpless. The breaking point for Peter was when he realised that he was prevented from accessing public healthcare in Gibraltar, as the Gibraltar Health Authority (GHA) requires identification for those seeking to access their services. This means Peter has no right to access public healthcare in Gibraltar. He has been left in the streets of Gibraltar, with no assistance from the Gibraltarian government.

“The way I’m feeling at the moment is [that] they don’t care if I die on the street. I served in Gibraltar for two years in the military. I’ve worked in the security industry. And they’re just leaving me, a 63-year-old man with a leg missing, out on the street. I’m getting weaker every day, trying to find somewhere to get out of the rain.” When asked about any friends or family back home in the UK that might be able to support him, he responded: “I was an only child. My mum and dad are both dead. I have a nephew and an uncle, but I haven’t seen them for so long they wouldn’t even recognise me. I’m all on my own.”

As the interview concluded, the reality of Peter’s daily life set in. While tourists walked by, he prepared for another night on a bench, hoping for a resolution from a government that seems to have forgotten him. I asked him: “Do you have hope that things will get better?” He replied, “I have to. Otherwise, what else is there? I have to try and stay strong and stay positive. But it embarrasses me. I never thought I’d be in a position where I’m begging on the street to survive.”

As winter sets in, this 63-year-old amputee waits on a park bench for a lifeline. His story is a stark reminder of how nothing can be taken for granted. Peter’s story stands as a unique case of abandonment in an overseas territory. If you would like to support veteran charities that help people in situations like Peter’s, please consider looking into the Royal British Legion or SSAFA. Other trusted charities include HHVUK.ORG and Shelter.

Comments