The paradox of loving to hate celebrities

In a society so heavily saturated with a culture of ‘celebrity worship’ and relentless over commodification, it’s unsurprising that every choice a star makes, especially financially, invites harsh criticism. Media outlets, driven by profit, flood us with access to celebrities’ private lives, thus exacerbating our urge to scrutinise their decisions and feeding into our impulse to judge. From the so-called ‘feminist’ Blue Origin trip, an 11-minute, Bezos-funded joyride into space with Katy Perry, to Nicolas Cage’s $276,000 ‘super-casual’ purchase of a dinosaur skull, later declared stolen and returned to the Mongolian government, it’s painstakingly clear that these bafflingly extravagant financial decisions feel so morally detached from reality – and who could blame us for scolding them in an actual living crisis. And yet, when celebrities like Elton John or Bill Gates – credited as ‘top certified philanthropists’ – donate millions to charity, public outcry still questions whether this is enough, raising the paradoxical question: do we enjoy judging celebrities?

The psychology behind our judgment: familiarity breeds criticism

Part of the answer lies in a surprisingly simple psychological concept called familiarity. The ‘mere exposure effect’ demonstrates how the more we see a face, a name, or even an idea, the more important or personally relevant we believe it to be. Celebrities who are plastered across social media and streaming platforms like Netflix or are in sponsored ads have become as psychologically familiar as our own family and friends.

And unfortunately, with familiarity comes judgment.

Familiarity tricks the brain into thinking, ‘I see them often; therefore, they matter to me.’ And people can’t help but judge those who matter to them

We critique celebrities the way we critique ourselves – instinctively, automatically, and often, even unfairly. Worse still, this ‘familiarity’ effect has integrated itself into what I’d like to call a ‘false fame phenomenon’, where frequent exposure has constructed people into appearing more famous, influential, or morally responsible than they actually are. Suddenly, a Love Island contestant, or a TikTok influencer with too much time and podcast equipment, is expected to share their political stances on war, climate policy, and economic inequality. Familiarity tricks the brain into thinking, ‘I see them often; therefore, they matter to me.’ And people can’t help but judge those who matter to them.

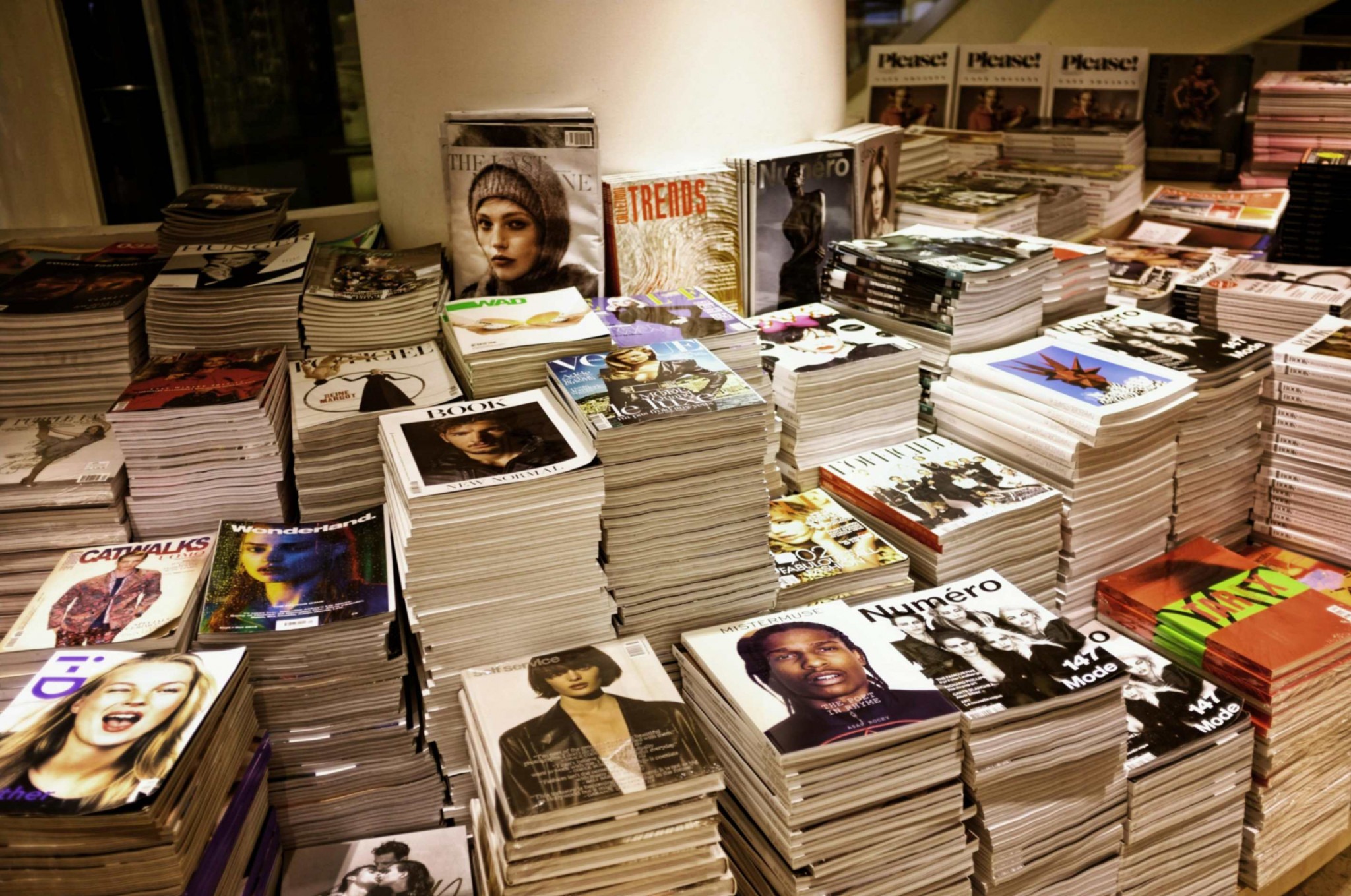

Consumerism and monetisation of the celebrities

Familiarity was accelerated by the pandemic. With the world stuck at home, we turned to our screens for comfort, a doomscroll, and a nice sense of distraction. Influencers and celebrities became many people’s daily companions, and when TikTok exploded, parasocial relationships intensified.

Out of this digital clutter emerged an army of micro-celebrities – creators with millions of followers whose entire lives are monetised.

What used to be innocent and relatable content, such as “get ready with me” or “day in my life” videos, became thinly veiled advertising. Alarm clocks, skincare, make-up, coffee pods: everything soon developed a discount code, an affiliate link, and a sponsor. Celebrities now market their lifestyles as though they’re doing their viewers a personal favour – “guys, you NEED this top, it changed my life.”

But, for the most part, audiences aren’t stupid. Most of us know that we’re being sold to, and that this relationship isn’t mutual. And so, frustration builds, which is channelled into judgment.

Celebrities are no longer relatable

It doesn’t help that celebrities are increasingly removed from the realities of a progressively harsh reality. As the living crisis tightens, celebrities post £5,000 skincare routines, £10,000 holidays and £30,000 birthday hauls. And the result? A widening gulf between the public and celebrities. So, when a star does something spectacularly out of touch, like Katy Perry’s ‘feminist’ space expedition, the backlash is volcanic. People call it wasteful, elitist, and environmentally catastrophic – and they aren’t wrong. But the intensity of the emotion reveals how we feel betrayed by people we’ve grown ‘familiar’ with, and that emotional closeness has created this ‘expectation’ for some moral accountability – sometimes absurdly so. We expect celebrities to donate enormous sums to global crises, to use their platforms flawlessly, to never misstep. And when they don’t? We judge. Harshly.

And when “people we know” make choices we don’t agree with, it feels personal – as though they owe us explanations and ethics

But even when celebrities give back, the criticism doesn’t stop. We scrutinise philanthropists for not giving more. Their generosity still feels insufficient, as though no donation could ever satisfy public expectation. The paradox is striking; we condemn their ostentatious spending, and yet, when they direct their wealth towards charity, we question their sincerity and commitment.

So, do we enjoy judging celebrities?

In a way, I suppose we do, but I don’t think that it’s with malicious intent. More often, we’ve confused familiarity with intimacy, and intimacy with entitlement. Because we see celebrities so often, on screen and in the media, they feel like people we know. And when “people we know” make choices we don’t agree with, it feels personal – as though they owe us explanations and ethics. We judge them in the same way that we judge ourselves.

If familiarity creates that illusion of closeness, then our relentless judgment may be less about their mistakes and more about our own expectations.

Comments