Dead man walking: The myth of a post-Neoliberal era

Since the shocks of the Brexit referendum, Donald Trump’s rise to power, and even the 2008 financial crisis, pundits have been quick to bury what they claim is the corpse of neoliberalism.

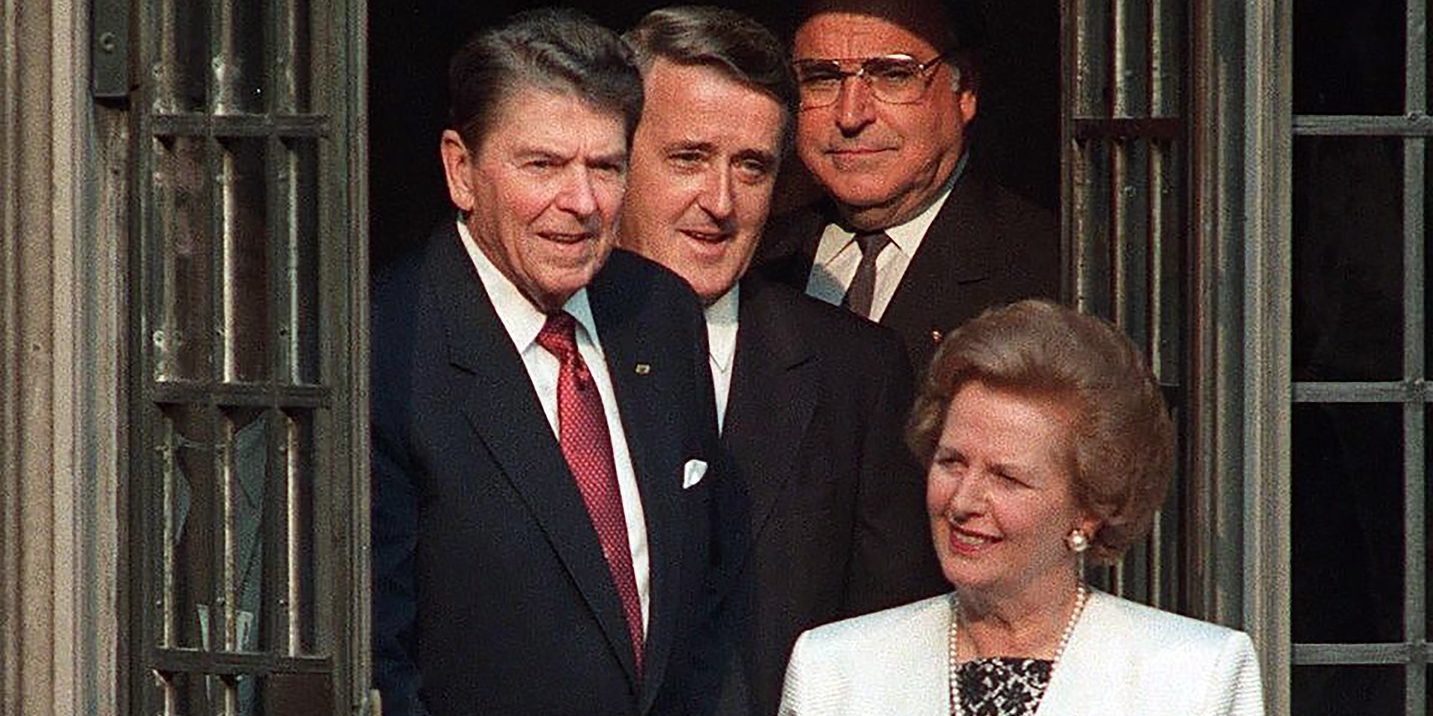

Once championed by Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan in the 1980s, the ideology has shaped the rules and language of modern politics as we know it. Although its figureheads have long passed and the term itself has fallen into disrepute, neoliberalism continues to pulse through Western politics, evident in the persistent prioritisation of economic growth and market-driven governance. In an era often defined as ‘post-neoliberal’, the lingering presence of its ideas raises a pressing question: if neoliberalism is truly dead, why does it still haunt the socio-political sphere?

Although its definition is contested, neoliberalism is broadly understood as an ideology that promotes economic liberalisation through deregulation, privatisation, free trade, and globalisation. At its core, it casts competition as the ‘defining characteristic of human relations’, redefining citizens as consumers, whose choices are best expressed through the market rather than a political vote.

Following decades of stagnant wages and recurring financial crises, public faith in neoliberalism began to erode. It became clear that its social Darwinist logic merely “recast inequality as a virtue”

Neoliberalism united those across the political spectrum around the belief that economic interdependence would foster global peace and prosperity. For the free market right, it meant minimising barriers that hindered market efficiency, while for the moderate left, it offered a framework for lifting the poor out of poverty through participation in global markets. This cross-party appeal enabled the initially popular policies of Thatcher and Reagan, who swiftly translated neoliberal ideas into practice through hefty tax cuts, weakening trade unions, and the introduction of market competition in public services. What began as a domestic experiment soon extended to the global sphere through the Washington Consensus, economic prescriptions promoted by institutions such as the IMF and World Bank to encourage liberalisation in developing countries. Often imposed without democratic consent, these policies accelerated the wave of hyper-globalisation that came to define the post-Cold War era.

However, following decades of stagnant wages and recurring financial crises, public faith in neoliberalism began to erode. It became clear that its social Darwinist logic merely “recast inequality as a virtue” – a sign that markets were rewarding talent and hard work whilst punishing inefficiency. Wealth, by this ideology, was a social benefit, expected to miraculously trickle down to everyone else. Efforts to correct this inequality were economically counterproductive, since inequality itself was essential to the system’s mechanism. Neoliberalism taught that success stemmed from merit, overlooking the structural advantages of class, inheritance, and education, while the poor were encouraged to internalise blame for their failures, regardless of circumstance.

The result was a widening gulf between neoliberalism’s promise of opportunity and its reality of only concentrated wealth. In the wake of mass disillusionment, neoliberalism began to falter. The post-2008 crisis response expanded central bank powers and relied on public spending to stabilise economies, rejecting strict free-market logic. This was more recently observed during the pandemic, where large-scale state funding and public health intervention challenged neoliberal ‘small-state’ ideals. Meanwhile, the younger generation, as observed through social movements and digital activism, has revived an interest in alternatives such as degrowth, universal basic income, wealth taxes, and climate justice, exhibiting a deviation from neoliberal politics.

Five years since the referendum, the British government has largely maintained its neoliberal policies – austerity has continued, and markets remain central to public services

Nonetheless, the political foundation created by neoliberalism has left a lasting imprint on our socio-economic structures. The evidence pointing to its supposed demise is often circumstantial, consisting of temporary departures from standard neoliberal ideals in response to crises that still leave market primacy, competition, and growth-oriented policies intact. Emerging anti-establishment rhetoric is failing to fundamentally displace neoliberal assumptions because the ideology remains deeply rooted within political institutions and policy frameworks, allowing dissent to be co-opted in ways that reinforce its underlying principles.

A primary example can be observed through Trump’s rise. Although he pitched himself on the basis of populism and anti-elitism, appealing to voters frustrated with inequality, his administration simultaneously enacted the very neoliberal policies that contributed to the frustration. In this sense, public rage against neoliberalism paradoxically reinforced its continuation. Trump’s victory was purely symbolic, projecting the facade of challenging a system that it only continued to perpetuate.

Brexit is another example of this. The campaign leveraged public resentment of austerity, immigration, and EU bureaucracy, promising to take back control. Yet, five years since the referendum, the British government has largely maintained its neoliberal policies – austerity has continued, and markets remain central to public services. Like Trump’s administration, Brexit offered redirection whilst keeping its existing economic logic intact. In both cases, the legacy of neoliberalism persists, albeit in a more covert manner. This entrenchment is particularly detrimental because it preys on disenfranchised voters, misleading them to support policies that limit their own opportunities.

Neoliberal thought has reoriented democracy away from the aim of a ‘greater good’, and instead around the pursuit of wealth and productivity

Concurrently, neoliberalism continues to breathe through political language. Even as explicit support for the ideology declines, its vocabulary, centred around efficiency, competition, and growth, remains pervasive in governance. Political discourse has adopted idioms of the free market. Citizens assume the role of customer, and public policy is judged by efficiency and return on investment, rather than by its capacity to promote welfare and equality. Even the promises of progressives often mirror corporate language, claiming to ‘invest in the people’, treating voters as an asset, much like their right-wing opposition.

Neoliberal thought has reoriented democracy away from the aim of a ‘greater good’, and instead around the pursuit of wealth and productivity. We are conditioned to believe that income and output directly correlate with social value, even though the elite profit above all else. In this way, market rationality has come to severely intrude on democratic life. Much like in neoliberalism’s prime, moral worth is equated with productivity. The repeated emphasis today on ‘hard-working families’ and ‘self-reliance’ reinforces the belief that success is earned through participation in the market, not collective wellbeing. As a result, neoliberalism not only continues to inform policy but also moulds the discourse itself. Its vocabulary is now embedded in modern political vernacular, helping sustain the very status quo it created.

Ultimately, despite widespread recognition of its deleterious impacts on social welfare and effective governance, neoliberalism remains ingrained – both in the political institution and within public discourse. Having shaped the post-Cold War era and the onset of economic globalisation, the ideology is now cemented into the very foundation of modern politics.

Moving beyond neoliberalism would require a fundamental shift in political priorities – leaders must place collective welfare above economic growth, and success must be decoupled from market performance. A genuine departure from neoliberal logic demands mass education and social rejuvenation, because so long as these values remain unchanged, power will continue to be concentrated within elite circles. Until then, the supposed death of neoliberalism is only an illusion. The ideology continues to influence us, shaping the world we claim it has left behind.

Comments