The Heart of the Matter – vexing or profound?

Graham Greene’s 1948 The Heart of the Matter is a book that simultaneously frustrates and demands much of its readers. Set in an anonymous African Colony in West Africa, it centres around British colonial police officer Henry Scobie, and his downward turn from moral righteousness to suicide, and his catholic fixation with guilt and pity that goes along with it. Greene’s novel is emotionally complex, yet the recurring contradictions within it leave it as vexing as it is profound.

One of the book’s strengths is its ambition. Through Scobie, it becomes a discussion of good and evil, the limits of human knowledge, the limits of inward morality and outward religiosity that tears at Scobie’s soul. The almost anonymous Scobie is not just a man guilt-ridden by adultery or loving a woman who is not his wife, but an emblem of Greene’s obsession with the “damned good man” – the divided self. Scobie is a man torn between love and duty. The Heart of the Matter is, to me, a verification of Saul Bellow’s claim in his 1944 novel Dangling Man that “the world is both [good and malevolent], and therefore it is neither”. Scobie’s suicide emerges as an acknowledgement of this claim, and his decision is not an impulsive act but a deliberated one. A tragically flawed gesture to himself and to the torture inside.

It was an attempt to fully show his intent, to give the reader an image of himself and another image of the reader

This in itself is a central problem. Greene was unsatisfied with how his readers interpreted Henry Scobie. The tragedy was often lost on them, seeing him as noble rather than tragic, as pointed out by critics like David Higdon. Greene was so moved by this that he revised his book in 1971, making over 300 amendments due to “a technical fault rather than a psychological one”. It was an attempt to fully show his intent, an attempt – as Wayne Booth argued, was the role of any writer – to give the reader an image of himself and another image of the reader. However, despite these efforts, we arrive at the same sentimental view of Scobie that Greene made pains to eradicate: a lowly martyred figure, a vessel of grace rather than a warning against ego and pride. It was the effort to re-jig the reader’s emotional and ethical response to Scobie’s downfall through Scobie’s revised internal monologue that creates an inconsistency in tone throughout the novel.

A further limitation of the novel is the problem of motivation. Henry Scobie’s decision to take the Eucharist whilst in a state of mortal sin, and his affair with Helen, a young widow, appear to be driven by the hidden demands of a religious allegory. A gap between decision and character is created, and the moral immediacy of the story is diluted. Greene, who once asserted in an interview that he was “a Christian agnostic”, crafts a central figure whose logic is both firmly rooted in Catholicism and infuriatingly opaque. The result: a man who, despite being the focus of a novel devoted to spiritual analysis, remains unseen.

Greene’s Catholicism casts a long shadow over the novel. Religiosity becomes an essence, a driver of pain and action, not mere performance

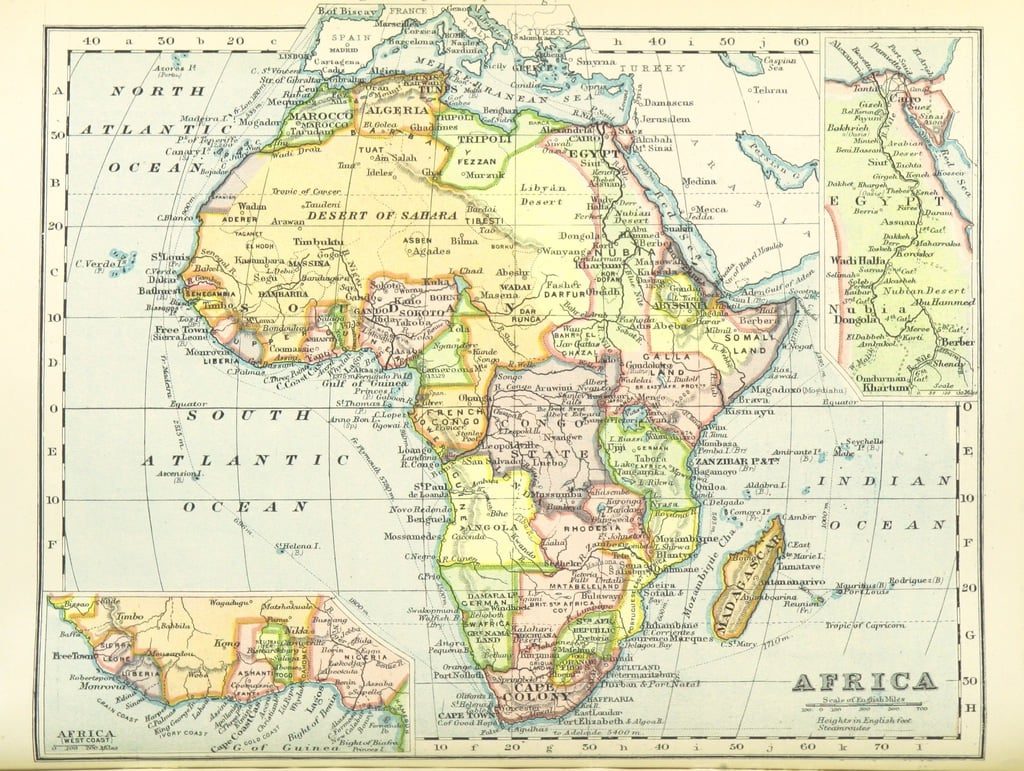

Despite these shortcomings, the atmospheric depth redeems the novel slightly, along with the space it occupies as a post-war, post-colonial read. Its setting is harsh, a moral landscape of corruption and crime reminiscent of Armah’s The Beautiful Ones Are Not Yet Born, yet fired from the other end of the spectrum: oppressor, not oppressed. The heat, the damp, the cloying loneliness all feature in both novels; they are just tools for different things. Armah wanted to show the colonial drain and make a political statement; Greene took a deeper, more spiritual route towards disintegration. We can possibly see the unnamed colony – confirmed as Freetown, British Sierra Leone by Greene in his 1980 memoir – as a purgatory for Scobie. Yet the blind spots are evident, the native characters are either voiceless or evil – reflecting the inherent neurosis and racism of their colonisers – the colonial setting feels more like a colour or shape than a real place. Greene’s vision of his unmarked territory where rules seem to go out the window is not so much malicious as indifferent. Scobie is free to do as he pleases, make a deal with any criminal, and choose to ignore evidence of malpractice as he wishes. Despite the deep sense of place, Scobie’s surroundings feel thin.

Greene’s Catholicism casts a long shadow over the novel. Religiosity becomes an essence, a driver of pain and action, not mere performance. As Scobie crumbles and damns himself, we are asked: Can moral failure produce spiritual insight? A bold question that is undermined by the contradictions of the novel. How can Scobie be damned to hell but still be owed empathy by his narration?

The novel’s weaknesses, its drawn-out character motivation, its structural second-guessing, and overdetermined symbolism are all things that still make it an interesting read. For all of Greene’s efforts, The Heart of the Matter emerges with more questions of what this heart might be than answers.

Comments