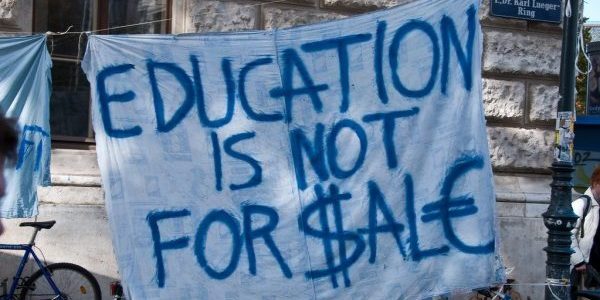

In line with inflation: Is Labour’s new tuition fee approach fair?

On Monday 20 October, Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson announced that Labour will “increase undergraduate tuition fee caps for all higher education providers in line with forecast inflation for the next two academic years.”

It is a headline that comes only a year after the government increased tuition fees by £285 last November, and during a period Labour remains unpopular nationally, particularly amongst young people.

So, it begs the question: Why pass the policy? And will it benefit UK universities that are under immense strain?

In its defence, the policy has been carefully crafted to be somewhat easy to digest. After the bitterness of having tuition fees reach over an expected £9,900 per year, Labour decided likewise to increase maintenance loans in line with inflation to ‘help the medicine go down’ more smoothly. Indeed, many students are likely to welcome the loan’s support.

Still, as Phillipson offers this ‘balanced’ policy and suggests that only universities offering high-quality education will be able to charge full fees, millions of students across the UK are brought to wonder about the fairness of it.

When institutions or previous policies fail, it is undoubtedly the students who take the fall

On the one hand, a higher tuition fee cap would provide a much-needed economic boost for universities struggling with slowed revenue. It would also encourage several universities to offer better-quality services and graduate prospects to their students.

Yet, when institutions or previous policies fail, it is undoubtedly the students who take the fall. Today’s students already face record levels of tuition debt, averaging around £53,000, soaring accommodation costs, and uncertain job prospects. Adding more to this financial burden (even in the form of a loan) risks young people feeling increasingly priced out of higher education.

The post-Brexit era has brought a sharp decline in the number of international students, ongoing economic mismanagement, and plans to cut the number of students able to attend university. Thus, it would be unjust to hold today’s students responsible for fixing the backlash stemming from poor government decisions.

Universities across the UK do require a much-needed capital boost, and this policy can bring about a resolution – I will not discredit that. Nevertheless, raising that capital by increasing tuition fees not only limits the expansion of accessible education but also falls short of the revenue needed to address the current situation. Many students would feel there are fairer, more sustainable, and more popular ways to keep universities afloat.

Universities are major hubs for local and national economic growth, providing thousands of jobs, customers, and tenants

The two biggest factors troubling universities are the significant internal mismanagement and decline in international students. Whilst Labour’s tuition fee adjustment may mitigate some of the impacts, the more attractive steps to get Britain’s higher education industry back on its feet would be to directly increase international student numbers to pre-existing levels and ensure university management failings do not occur.

Brexit, tighter visa restrictions imposed by past and present governments, and growing competition from countries like Canada and Australia have made the UK less attractive to overseas students. Combined with the after-effects of the pandemic, the situation has only worsened. Several universities, including Cardiff and Sheffield, have been accused of overspending and generating debt that led to a staggering number of redundancies across the nation. It is important to remember during such large systemic changes – like Brexit or the subsequent increase in tuition fees – that universities are major hubs for local and national economic growth, providing thousands of jobs, customers, and tenants.

More student-friendly visa policies, rethinking the cost of research grants as inflation rises, or diversifying revenue streams would all help tackle some of the system’s greatest problems

If the government really does want to stabilise higher education, a vital issue in the Education Secretary’s portfolio, there are more equitable routes that are seemingly being ignored for political ease. Solutions such as creating more student-friendly visa policies, rethinking the cost of research grants as inflation rises, or diversifying revenue streams would all help tackle some of the system’s greatest problems. Strengthening financial oversight would also help avoid the comedy of errors repeatedly seen in institutions.

Such policies would be more time-consuming to pass through the House of Commons and the Lords and to eventually implement. However, they would relieve the pressure on students to elevate these universities whilst also tackling deep structural issues.

UK universities are in a funding crisis. Naturally, the government has taken steps to avoid collapse before it is too late. But, from September 2026, we will feel the response. And this rise in tuition fees will make us consider what needs to be done to create a more sustainable and accessible education system.

We must take the time to broaden our view of higher education and tackle the structural failures plaguing Britain’s universities.

Comments