Heists – The Louvre and Beyond

L’art pour l’art, or rather, art for art’s sake. Victor Cousin’s phrase was one of the key springboards of the Aesthetic movement in France, a period of art history wherein there was a focus on the simple beauty of art, rather than the moral purpose or meaning behind the piece. But when this art goes missing, what is left in the aftermath reveals more about the way we view art as a part of our cultural history and national identity.

Boasting nearly nine million visitors a year, it leads one to wonder how anyone could even dream of stealing any one of the priceless works housed there

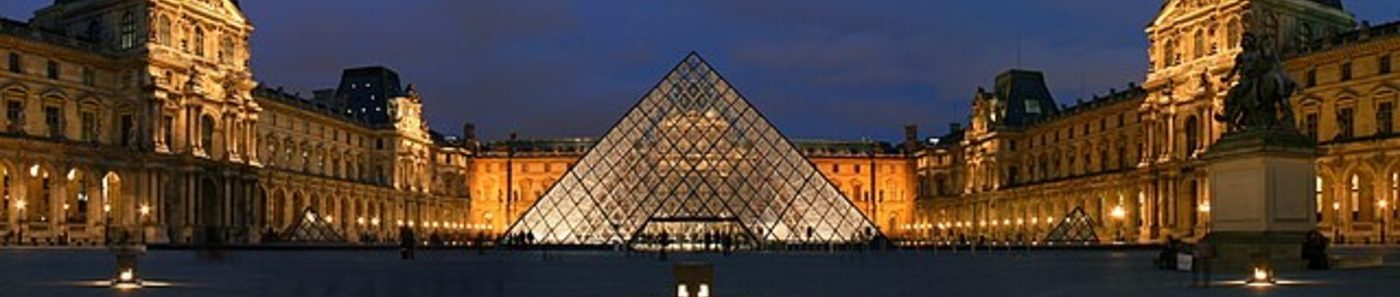

The Louvre Museum is one of the most famous museums in the world. In the three centuries since it first opened, the museum has ingrained itself as an essential part of France, containing much of its history from the early modern until today. Boasting nearly nine million visitors a year, it leads one to wonder how anyone could even dream of stealing any one of the priceless works housed there. But people did.

On the morning of the 19th October 2025, the suspects arrived at the Louvre around 09:30am local time, gaining access to the Galerie d’Apollon (Gallery of Apollo) via a mechanical lift. From there, the gang were able to make their way inside the museum, cut into the glass displays holding the jewels, including a diadem set with 212 pearls, nearly 2000 diamonds that belonged to the wife of Napoleon III, Eugénie, and an emerald and diamond necklace that Napoleon I gave to Marie Louise, his second wife. At the time of writing at least one suspect remains at large, while four have been taken into custody. As expected, the heist garnered an outcry of outrage from the French public and government alike, with French president Emmanuel Macron calling it “an attack on a heritage that we cherish because it is our history.” The crown jewels are one of the symbols of the French monarchy, an establishment the French themselves abolished not once, but twice, the former of which has gone down in history as one of the most famous revolutions of the early modern period. For a nation so well-known for their dislike of the monarchy, why are symbols of that regime so important to their memory?

Therefore, it can be argued that the jewels were significant insofar that they were representative of the French pride of their history, in their revolutions and coming to the modern day the way they have

Rather than the jewels themselves, it could be seen that the heist and what they represent were what caused such an outcry. Benedict Anderson proposed the idea of a nation as an ‘imagined community’ because while its people will never know all of their fellows, they have a sense of comradeship formed through the perception of shared experience, a factor in the spread of nationalism. France has a long history of nationalism and patriotic attitudes, much of which stem from the French Revolution of 1789 and onwards – the shared experience of suffering and liberation. Therefore, it can be argued that the jewels were significant insofar that they were representative of the French pride of their history, in their revolutions and coming to the modern day the way they have. A way of longing for the past that seems unreachable. David Lowenthal argued that we have such a fascination with history, our own and otherwise, because “every facet of life fled the failed future for some consoling past”. For the French, this past is reconstructed through the Louvre and it’s displays, shining light on why art is often tied deeply into the history of a country, and a core part of national identity for many.

Surprisingly, the year’s heist is not the only time the Louvre has been robbed. In 1911, former employee Vincenzo Peruggia, stole da Vinci’s ‘Mona Lisa’. Da Vinci was, and still is, one of the most important figures of the Renaissance in Italy, with his work spanning across multiple disciplines, from art to science. Today, his most famous work remains the ‘Mona Lisa’, despite its association with France due to being held in the Louvre. The theft is a point of comparison today with the most recent heist of the museum because of Peruggia’s motive for the robbery – patriotism. Peruggia was deemed a hero by the Italian public and given great leniency – only seven months in prison. Arguably, this opens up discussion about how deeply art is intertwined with national pride. The majority of da Vinci’s works are held in Italy, but the ‘Mona Lisa’ ended up in France after being sold by his apprentice. To Peruggia, returning the portrait to Italy may have only been fitting, as it is a part of da Vinci’s legacy, something that is tied to the cultural history and identity of the country, just as the Crown Jewels were to France. However, it can also be argued how the ‘Mona Lisa’ only gained the fame it has today through the heist, as many visitors flocked to the Louvre to see it following its return to the museum. Despite this, it remains to be seen that art is integral to the national identity of a country, formative of the experience that cannot be expressed in any other manner.

The 2025 Louvre Heist reveals how art is tied much more deeply into a nation’s subconscious – through its cultural history and identity – than may have initially been thought

Glamourised as it is on social media, the 2025 Louvre Heist reveals how art is tied much more deeply into a nation’s subconscious – through its cultural history and identity – than may have initially been thought. The human inclination to create and interpret art has played a major part in shaping our perception of our histories today.

Comments