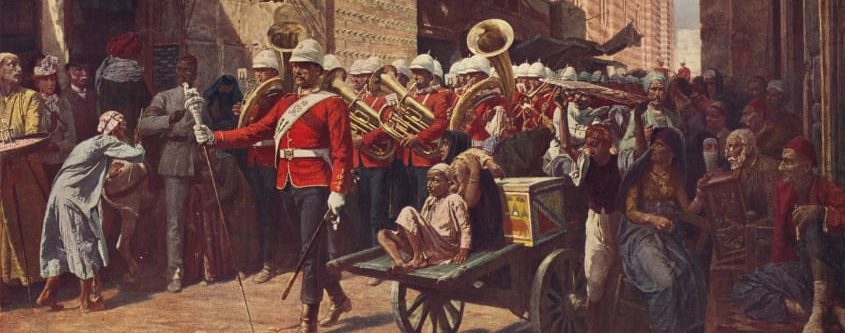

The contestation of British identity: tracing back the thread of Empire and the British-Asian experience

Immigration in Britain has always been a fiercely debated topic. From 1965 to 2025, the current political climate is dangerously starting to mirror not just the racism and hostility towards Commonwealth migrants during the 1960s and 1970s, but also a much more complex issue. Media outlets from the likes of The Sun and The Daily Mail perpetuate anti-immigrant rhetoric that fabricates a parochial narrative scapegoating immigrants, particularly non-white immigrants, as the enemy. They perpetuate a nationalist, white, ethnic purity for Britain to ‘return to’. This populist rhetoric points a finger at this minority for problems that the government has failed to address, especially among working-class audiences that right-wing newspapers cater to.

However, this is nothing new in Britain. If anything, the issue of immigration under Starmer’s Labour government shares parallels with that of their predecessors almost six decades ago, under Harold Wilson and Edward Heath’s administrations. The fact that the Prime Minister exclaimed that Britain ‘risks becoming an island of strangers’, fuels anti-immigration agendas, especially as it directly references Conservative politician Enoch Powell’s ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech and echoes populist right-wing sentiments.

My British identity went deeper than just being born and having familial ties in the country. Rather, these familial ties did not just extend to my grandparents coming to the UK in the 1960s, but actually several generations back to the British Empire and its colonial rule over India and East Africa

These very parallels confronted me with the question of what it actually means to be British amidst such nationalism, especially as someone who is non-white. For some, their British identity can be affirmed through hanging the Union Jack outside their house or parading it in public places, like the protesters at the ‘Unite the Kingdom’ march. However, for me, it was not something you could just represent with a flag.

I always considered myself British because my family have lived in and contributed to this country for three generations. However, throughout the process of the Undergraduate Research Support Scheme (or URSS, a self-directed, academic research project funded by the university), I chose to focus on Asian experiences in Britain during the 1960s and 1970s, and I came to a realisation. My British identity went deeper than just being born and having familial ties in the country. Rather, these familial ties did not just extend to my grandparents coming to the UK in the 1960s, but actually several generations back to the British Empire and its colonial rule over India and East Africa. This project raised a serious question about my British identity that was more than just a flag. For me, it meant connecting with the genesis of what I considered to be even making me British: my grandparents.

Not only were my ancestors British subjects, but they held British passports too, a tangible representation of their ‘British-ness.’

Bloomberg journalist and broadcaster, Mishal Husain, explores a similar realisation in her book, Broken Threads, which expands on the reconfiguration of her identity from being a daughter of an immigrant to the granddaughter of a British subject. This rang true for me. It challenged my neat identity box from being a third-generation immigrant, to just like Husain, a granddaughter of British subjects.

Not only were my ancestors British subjects, but they held British passports too, a tangible representation of their ‘British-ness.’ But even this was not enough. In the case of my grandparents, who were British Commonwealth citizens holding British passports, they were subject to the immigration resistance that became a defining feature of the Wilson and Heath Labour governments. In 1968, Wilson’s government oversaw the Commonwealth Immigrants Act, which targeted Asian populations migrating from Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania. The legislation aimed to reduce the number of Commonwealth citizens entering the UK, as it removed British passport holders unless they had a relationship or connection already in Britain.

Often, Asian experiences in Britain are usually told against the background of Britain’s socio-political situation. However, the premise of my URSS project was to use oral history, an interview-based methodology, to magnify these experiences and bring the Asian migrants’ history to the forefront. Understanding this community’s lived experience confronted me with not just the reality of the dangerous impact anti-immigrant rhetoric perpetuates, but also the importance of history in living memory and its preservation.

In the surveys, which were anonymous, over half of them described their first impressions as positive, with some using adjectives such as “disciplined”, “welcoming”, and “exciting

Throughout the project, I attempted to find ways to hold on to these threads of history. I interviewed and carried out surveys with people of East African Asian backgrounds about their migration experiences to Britain, and ensured I did this in places where participants were familiar and comfortable. This included the local Mandir (temple) or their homes, in different parts of London. Each participant approached the surveys differently, with some even serving as informal interviews that went beyond the simple five questions I had ready. I took the time to sit down and properly discuss the participants’ experiences that went into far more detail than the surveys required, but what the interviewees wanted me to know. They wanted me to listen to their hardship, sacrifice, and struggles. From their wage per week to the price of bread.

In the surveys, which were anonymous, over half of them described their first impressions as positive, with some using adjectives such as “disciplined”, “welcoming”, and “exciting”. However, the people who described their impressions more positively in the surveys coincided with the fact that they came to Britain from Kenya between 1960 and 1965. This was before the Commonwealth Immigrants Act in 1968 and mainstream anti-migrant rhetoric in the political sphere. Surveys from participants who arrived after 1968, on the other hand, had more negative descriptions of their impressions, such as “miserable” and “shocked” and “very different”.

One participant, who is 90, articulated how after 1970, racism increased especially towards Asians from Uganda, and “discipline changed”, as opposed to her own less negative experiences when she came in 1965. She observed that the experience for immigrants then was “quite good, disciplined, and welcoming”. Though it is important to note these were the conclusions I drew from the surveys I conducted of a small sample out of the millions of Asian experiences, and this is not to say all experiences before 1968 were positive, and not all after were negative.

As a history student, I was fascinated by each and every story that the survey participants told me

The surveys also asked why the participants came to Britain, and the answers painted an almost perfect picture of global politics during this period. For instance, many answers referenced the impact of Africanisation policies in Kenya and Uganda on Asian people. Some were subtle, “my job was given to [a] Kenyan citizen” and “we were evicted from the country”, and others were more direct, “my husband’s job was being Africanised”. Other answers stated that there were “problems in Kenya” and that they had “British passports”, implying that they were almost returning to the motherland of the Empire. As a history student, I was fascinated by each and every story that the survey participants told me.

The very last question I asked each of them was if they would like me to formally record their experiences for an archive, the Modern Record Centre (MRC). That was another part of my URSS project I was determined to do. I wanted their experiences during the colonial and post-independent periods in East Africa and Britain to serve as a form of oral history, deserving of being publicly remembered. More importantly, I wanted it to be celebrated, especially given the long-held right-wing media’s narrative of immigration. However, only three, out of the dozens I spoke to, agreed to have their interviews formally recorded and archived in the MRC: my grandparents and aunt.

The formally recorded interviews were much longer than the informal interviews I carried out alongside the survey distribution. It gave me more time to properly investigate and explore my family’s experiences. These interviews, now available in the MRC, explore a range of topics that range from factory work in the 1970s, first-hand experiences of the Polio epidemic, and the British education system.

They also offer a richer insight into the participants who had lives before migrating to this country. They were not just immigrants. They were people with ambitions, searching for opportunities that Britain offered them. They endured hardship, racism, and discrimination.

Understanding my family and community’s experiences was necessary for me to comprehend my own British-ness as a thread, part of a wider tapestry of not just the British Empire, but Britain today.

Comments