Re-evaluating the British Empire: Cotton, colonies and controversy

Research from the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA) in 2024 suggested that the British Empire was not as large a historical source of wealth as one might think.

Colonialism and the slave trade have been declared as “at best, minor factors” and perhaps even “net loss makers” in the era of British imperialism. This effectively undermines the impact of British colonies and slave labour on the mass production of raw materials, the Industrial Revolution, and the historical economic growth leading up to modern-day Britain.

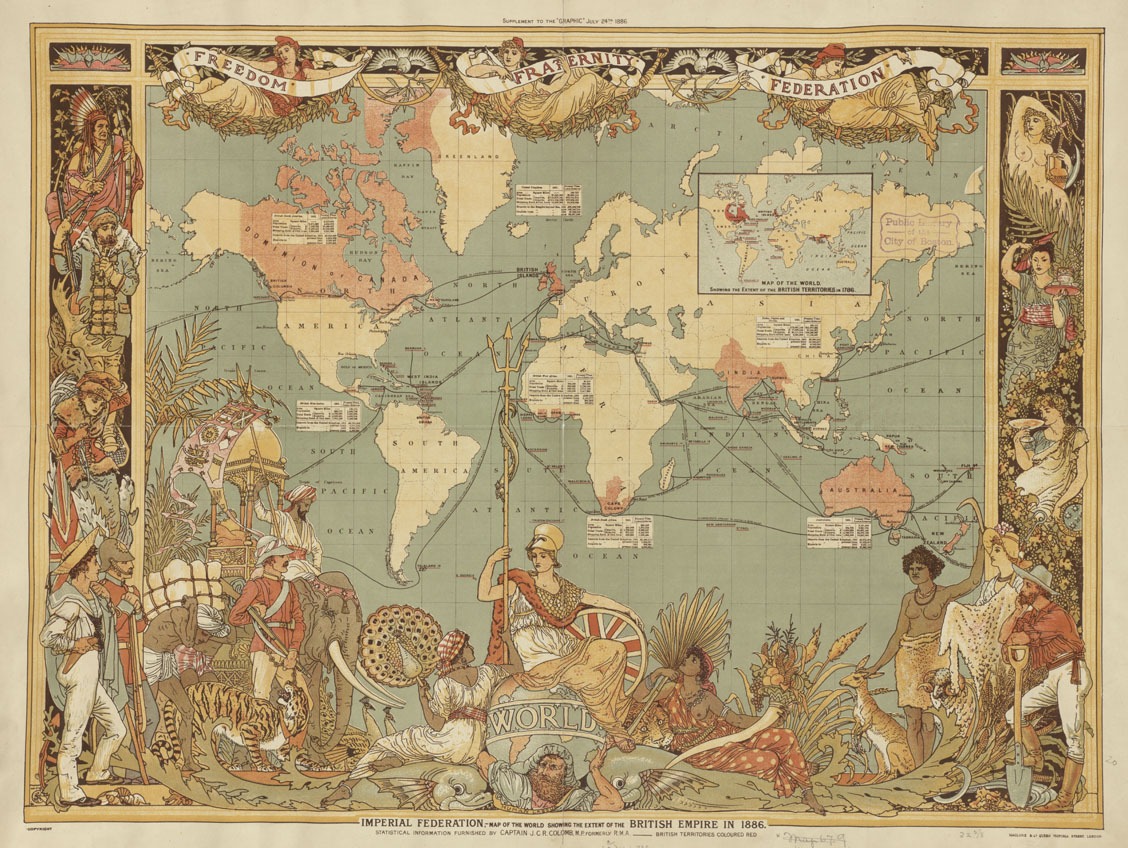

The British Empire, begun in the late 1500s, was the largest in world history. The IEA released “Imperial Measurement: A Cost-Benefit Analysis of Western Colonialism” last year, a report that attempts to falsify the empire’s history of imperialism and the slave trade as “capitalism’s original sin.”

Given the research findings, Business and Trade Secretary Kemi Badenoch stated that “colonialism played a minor role in Britain’s economy” and that “it was British ingenuity and industry… that powered the Industrial Revolution and our modern economy.”

The IEA states that slave-based sugar plantations, one of the most profitable plantation types in the colonial era, contributed just under 2.5% to the British economy at its peak.

However, especially considering past criticisms of the IEA as “promoting extremist views”, does such research present a biased and avoidant narrative of British colonial history?

Such a discussion requires deeper reflection on the role of plantations and colonies in the British economy and on how the nation weighs their costs today.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the English crown prioritised control over trade and shipping in its colonies by granting them monopolies on their products. Said products corresponded with the ever-increasing necessity for raw materials in the British market, such as sugar.

The IEA states that slave-based sugar plantations, one of the most profitable plantation types in the colonial era, contributed just under 2.5% to the British economy at its peak – notably less than the share of sheep farming, or brewing.

However, what is the impact of minimising the economic gain of colonialism, and instead attributing this to British greatness? British spokespeople overwrite the unpaid labour of enslaved communities, instead with the celebration of “free markets and liberal institutions” as driving Britain’s economic growth during and after the Industrial Revolution.

As The Guardian journalist Maya Goodfellow pointed out in 2019, Britain uplifts itself as “the saviour, never really an oppressor”, by perpetuating the success of the British economy as due to an “innate ability to progress”.

Sugar’s economic importance was eventually overtaken by cotton in the late 18th century, as the textile market expanded to meet demand for resources, such as clothing, especially amongst the middle class.

At this time, cotton accounted for around 16% of Britain’s exports, and this figure rose to around 42% just a few years later in the early 1800s.

Though the trading of enslaved people was abolished by the British Parliament in 1807, those already enslaved were not protected, causing free slave labour to continue for around 30 more years before slavery was abolished in most British colonies. By 1830, around 750,000 enslaved Africans in the British Caribbean continued producing commodities like cotton, sustaining Britain’s reputation in the global market.

In 2023, the Brattle Group’s Report on Reparations for Transatlantic Chattel Slavery concluded that the UK alone would owe $24tn (£18.8tn) in reparations across 14 countries.

Between 1800 and 1860, Britain’s cotton exports increased from £5.4 million to £46.8 million. As global competition rose, Britain established a monopoly over the cotton market, given its colonial rule over India and other economic threats.

Though the IEA does not explicitly highlight the significance of cotton trading, it does fairly explicate the high costs of the British Empire’s commercial domination.

The IEA suggested that “significant military and administrative costs [and] higher taxes” outweighed the long-term financial benefits of British imperialism.

The popularity of cotton, which catalysed the innovations of the Industrial Revolution, led Britain to invest heavily in new technologies and mass-production methods.

Despite cotton being durable, a cheaper alternative to silk, and easier to print than wool, the wider costs of colonialism and the slave trade may not be so much indicative of the British Empire’s accumulated wealth as of the high long-term price.

In 2023, the Brattle Group’s Report on Reparations for Transatlantic Chattel Slavery concluded that the UK alone would owe $24tn (£18.8tn) in reparations across 14 countries. Such a debt is evidently a massive, expensive, and, as the IEA suggests, perhaps inevitable drawback of Britain’s past dominance of the global market.

Yet the point still stands that to imply that these high costs and the long-term debt are enough almost entirely to cancel out the economic advantages is a strong claim. Could it be right for Badenoch to say that this is a “reminder that state overreach is always an expensive endeavour”, dismissing the profits of colonialism as negligible in comparison to its costs?

If so, the claim is both delicate and insensitive. It waters down the exploitation of millions across history, instead presenting Britain in a heroically self-subsisting light. Statistics aside, a moral debate arises from minimising any contribution to Britain’s economy rooted in colonial history.

Of course, the scope of the British Empire as a topic of criticism surpasses the limits of this article. To come to a rock-solid conclusion would be to consider every single cost, investment, and gain of British imperialism spanning centuries up to the present day – a task of formidable magnitude, given the broad mix of economic factors.

Comments