Prohibition and its legacy: What policymakers can learn

Several popular debates, including those on immigration, free speech, and the balance between policing and protest, spark controversy in various sectors of contemporary British society. Yet at a time in which debate is becoming increasingly tribal and vulgar, a subject that subverts this trend is that of a smoking ban, which grows ever more popular as traditional smoking declines yearly.

According to the campaign group ASH (Action on Smoking and Health), smoking costs England far more than it contributes through tax revenue. Banning smoking would have fiscal benefits, as the outlays on public services and the resulting productivity losses exceed the taxation brought in by the tobacco industry, costing the public purse a net loss of £9.7bn in England in 2024. Hence, the banning of smoking, a social policy by nature, would have positive economic impacts while contributing to the fight against other societal blights, such as poverty. In this context, a socially oriented financial policy appears not only widely popular, but also broadly beneficial.

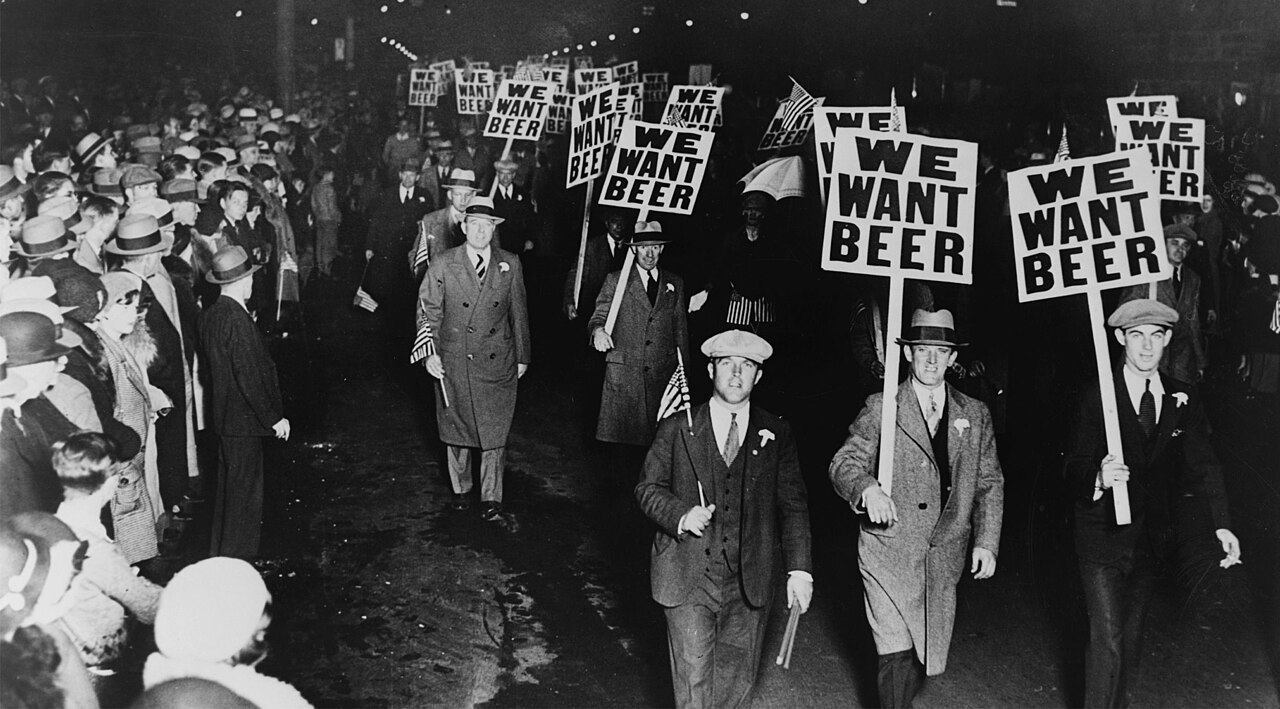

The USA’s alcohol ban was anything but. Instead, it offers a cautionary tale. The Eighteenth Amendment to the US Constitution imposed a complete ban on the sale of alcohol, forcing all Americans to cease their consumption of beer, wine, and spirits. However, Prohibition failed to remove alcohol as a staple of American society: it merely drove it underground.

It is hard to deny that Prohibition’s 13-year experiment was an overwhelmingly negative one

Debating the economic impacts of Prohibition, and disregarding its moral or popular dimensions, portrays the era in a dire light. By banning a particular product, in this instance, alcohol, you attempt to sever the supply. Over time, this in turn quells the demand. However, alcohol production continued during Prohibition. Initially, alcohol consumption dropped to comply with the new legislation, but this was followed by a steady increase, which culminated in alcohol consumption peaking at up to 70% pre-Prohibition levels. This can only be partly explained by alcohol produced before Prohibition, which would have decreased over the 13 years it was in effect, yet alcohol consumption itself only increased over time. Hence, even though challenging to statistically track, production continued en masse, partially encouraged by Prohibition itself.

The financial incentive for black marketers was immense: higher selling prices, no taxes or marketing costs, and no need to follow health and safety regulations made the illegal selling of alcohol an obscenely lucrative venture. Moonshiners and bootleggers thrived, reaping in a suddenly enlarged bottom line. The sole cost was the risk of being caught – a minimal risk, given that enforcement from authorities was often patchy and discriminatory.

Alcohol, especially beer, went on to help tackle the Great Depression, providing employment opportunities and a new stream of federal tax income

As supply didn’t halt, the intended impact of killing demand for alcohol never surfaced. The USA is a nation built around the concept that the state and the individual should be separate entities, and America was, and to some extent still is, a cultural entity that could never have tolerated such a direct attempt to control private behaviour. The popularity required for the Eighteenth Amendment to pass through the amendment process was largely comprised of a small subset of the core temperance movement, and large swaths of performative support. These individuals were ready to present the desire for the end of alcohol consumption, but were unwilling to give it up themselves. Prohibition had surface-level popularity, but never truly resonated within the social fabric of American society.

Amid a ream of constructive policies aimed at rewiring the American economic system, Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) joyously oversaw the end of Prohibition, with the Twenty-First Amendment rescinding the Eighteenth in 1933. It is hard to deny that Prohibition’s 13-year experiment was an overwhelmingly negative one. It failed to tackle alcohol consumption, closed a major industry which employed around a quarter of a million, and was never aligned with the US’ cultural psyche of freedom-loving independence that is distinctly separate from federal power. Prohibition was a cyclical and structural economic detriment: a social experiment destined to fail, given the petri dish in which it was tested. The Twenty-First Amendment is the only example of a constitutional amendment rescinding another, providing another example to strengthen the idiom of acting in haste and repenting at leisure.

Alcohol, especially beer, went on to help tackle the Great Depression, providing employment opportunities and a new stream of federal tax income (to fund other New Deal projects). The legalisation of beer production became “the opening salvo” for FDR’s New Deal, with Massachusetts Representative Arthur Healey estimating it would induce $360 million to be spent in the economy for the means of alcohol production alone, alongside job opportunities and multiplier effects thereafter.

Blanket bans don’t work, but policy that aims to alter social standards can succeed

Drawing lessons from the US Prohibition period, it is clear that the outright outlawing of socially unpopular practices fails not only to rid society of such practices, but also can induce their own return through monetary incentives. Returning to the example with which I began, a smoking ban in Britain is, on social, economic, and cultural grounds, far more feasible. Firstly, the expenditure on smoking falls on our publicly funded health service, which means it is a net-negative in a manner incomparable to the US, which operates on a private health system. Secondly, the UK has a culture more accustomed to government intrusion to prevent objective harms, something far more absurd in American political culture. Hence, individuals are more willing to collectively accept social ‘nannying’ to prevent the health hazard of tobacco products perpetuating for decades to come.

However, it is still vital to consider the economic forces which allowed the presence of alcohol consumption to continue during Prohibition. The instantaneous blanket ban left the infrastructure for production and consumption, as well as a society ingrained with a strong drinking culture, still standing, preventing any substantial change to alcohol consumption. Therefore, a gradual process of illegalisation in the case of smoking, such as the (now defunct) New Zealand plan to raise the legal smoking age yearly to prevent future generations from ever accessing cigarettes, would be better adopted, as is the case in the UK. Although the legislation has yet to come into effect, it would create a “tobacco-free generation”, banning the sale of tobacco products to anyone born on or after January 1 2009. In doing so, the economic systems geared towards the manufacture and sale of such goods can be dismantled gradually under the close eye of state forces, preventing the creation of a sizable black market, such as that populated by moonshiners and bootleggers in early 20th-century America.

Prohibition was a policy destined to fail, producing little but criminal activity, an immense black market, and a significant cultural backlash. While we have moved long past the times of the Eighteenth Amendment, there are economic lessons to be learned about the nature of socially oriented fiscal policy, the implementation of product bans, and the economic forces that will attempt to incite their return. Blanket bans don’t work, but policy that aims to alter social standards can succeed, so long as it is gradual, economically aware, and genuinely supported by the public.

Comments