It’s funny and it’s horrifying: Humour and darkness in art

I wonder if I’m the only person who finds Andy Warhol’s 1976 series ‘Skulls’ to be mildly amusing.

Warhol apparently became obsessed with the idea of death after being shot and critically wounded in 1968, leading eventually to the creation of the ‘Skulls’ series, containing six versions of the same skull, with different colours overlapping each one. Warhol was contributing to the long line of artworks within the ‘memento mori’ tradition. The translation of the phrases from Latin is “remember you must die,” and it encapsulates the purpose of the artistic trope: the simplicity of objects in a still image is used to evoke both the inevitability of death and the fragility of life.

What is dark about the painting may not be the evoking of death, but the commodification of it by the artwork itself. There may be death, there may even be taxes, but don’t worry: there’s always something you can buy

However, while ‘Skulls’ does indeed have this function, the use of the vibrant colours, in juxtaposition to what we would expect and have seen a thousand times before, adds a layer of thematic depth, and playfulness, to the piece. Could Warhol be pushing us to subvert our view of death, and come to terms with it in a more accepting way? I’m skeptical, because in the context of the rest of Warhol’s pop art, where ubiquitous, everyday objects become the centre of attention, the utilisation of the skull as just another one of these items degrades its seriousness and significance. Indeed, when placed into this border context, one could even make the argument that it speaks to a certain commercial characteristic of society, where death is just another product. What is dark about the painting may not be the evoking of death, but the commodification of it by the artwork itself. There may be death, there may even be taxes, but don’t worry: there’s always something you can buy.

Warhol’s ‘Skulls’ then, is both dark and funny. Throughout the history of art, there have been many artworks that have been funny; albeit, with the meme-ification of culture, our brains may have thoroughly rotted to the point that we can find anything funny. I urge anyone with enough bravery or foolishness to go down the Internet rabbit hole of weird and esoteric Medieval art. There lies the weird and wacky, from stupid facial expressions to people getting swallowed by whales to trees sprouting male genitalia.

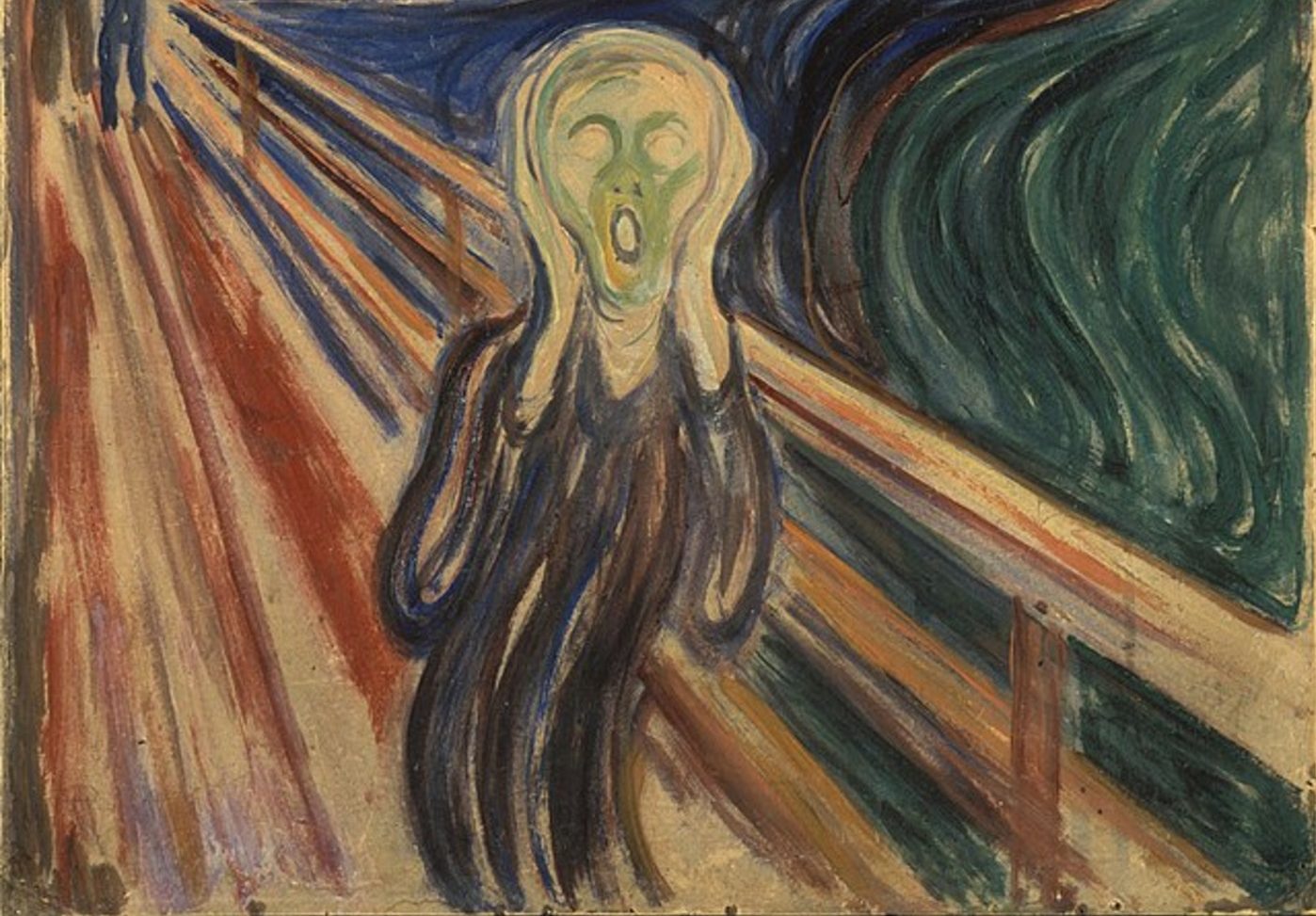

Personally, in the realm of things that weren’t meant to be funny in the way they’re funny now, I have to give my vote to Jan Matejko’s 1862 painting ‘Stańczyk’, featuring a depressed jester, sitting lonely and stressed. There’s something about the jester’s facial expression, of being completely just done with the world that is extremely relatable, and, consequently, ripe grounds for Internet-style humour. Edvard Munch’s ‘The Scream’, with its central agonised face, is similarly prone to being funny if you relate yourself towards it in the wrong way (me when an assignment is due tomorrow).

While there are people under the masks in Ensor’s works, not dolls, the masks still create a sense of stiltedness that evokes an underlying anxiety and uncomfortable absurdity

Now, while in the examples I’ve been giving the humour may or not be intentional, one artist that I think purposefully plays with both the dark and the purposefully is James Ensor. Ensor’s art doesn’t fit into a neat category, but he was influential in expressionism and surrealism. His use of masks, a continuous motif within his work, is especially interesting. In the iconic 1890 piece ‘The Intrigue’, featuring a strange and grotesque group of strangers, the masks the figures wear creates an uneasy atmosphere. It’s the same way a doll can be creepy due to their being just close enough to see that it’s meant to be human, but just off in a way that our brains recognise the thing as something alien and other. While there are people under the masks in Ensor’s works, not dolls, the masks still create a sense of stiltedness that evokes an underlying anxiety and uncomfortable absurdity. The oscillation between the humorous and the haunting would be taken up by the Surrealist movement during the 20th century.

That being said, I find it curious that ‘the absurd’ has recently wormed itself back into our art: however, unlike the 1910s, the weird is derived from artificial intelligence, and not humans

I think art that plays with both the dark and the funny can be incredibly thought-provoking and engaging. This intersection seems more relevant today than ever before, where the underlying seriousness of societal issues including climate change, oppression and inequality are mixed together with the unseriousness of internet culture. Of course, how art will deal with the dark and the humorous as we accelerate to a seemingly inevitable socio-political cataclysm is a question for another time.

That being said, I find it curious that ‘the absurd’ has recently wormed itself back into our art: however, unlike the 1910s, the weird is derived from artificial intelligence, and not humans. Like Ensor’s painted masks, AI art produces a visceral reaction in the viewer, of something being just off. It is not only the content within the artwork but the artwork itself that has now become absurd. AI art is commonly both funny and horrifying. Yet AI doesn’t know what’s funny, and it certainly doesn’t know what’s dark. What ‘Skulls’ conveys so brilliantly AI does automatically, for AI simply sees the skull as just another object. The art AI produces is nearly exactly the same as ours: it looks similar, and in the grand scheme of things, its method of producing a work isn’t too far off ours. The only problem is that it lacks a soul, and to that, I’m not sure whether I should laugh or cry.

Comments