This is America, still: The value of protest music

Music, in all its forms, has long been a vessel for joy, escape, and imagination. But while songs can lift us out of our everyday lives, they can also root us firmly within them, grounding us in a reality which is not always comfortable. As the American singer, Nina Simone, once said: “An artist’s duty, as far as I’m concerned, is to reflect the times.” Some forms of music not only hold up a mirror to injustice, but do so in a way which provokes, protests, and makes real noise. Protest music spans generations; from the Vietnam war to the more recent Black Lives Matter movement, the soundtrack of resistance has evolved, but its purpose remains the same.

One of the most iconic voices of this tradition is Marvin Gaye, whose 1971 album What’s Going On captured the turbulence of his time. The album was released at the height of the Vietnam War and is told from the point of view of an American soldier returning to witness even more suffering and injustice on home soil. The title track, though it questions the necessity of war and brutality, emphasises the importance of compassion in order to conquer hate. The song opens with the melody of a saxophone, lending a jazzy texture that recalls the use of jazz music as a vehicle for black expression during the Civil Rights movement. Beneath the layered harmonies and groove you can hear the urgency in a man’s voice who is simply pleading for a better world.

Kendrick Lamar’s chorus became an anthem of hope and reassurance

Three years later, Stevie Wonder released the 1974 album Fulfillingness’ First Finale, including the track You Haven’t Done Nothin’. Released amid the fallout of the Watergate scandal, the song voices frustration with Richard Nixon’s unfulfilled promises and evasive leadership. It jerks between scathing, accusatory lyrics such as ‘we are sick and tired of hearing your song’ and the playful, bordering on mocking, backing vocals of the Jackson 5, chanting ‘doo-da-wop’. The track showed Wonder as a figure who used his platform to challenge white-led authority and demand accountability, something which celebrities in the modern day shy from.

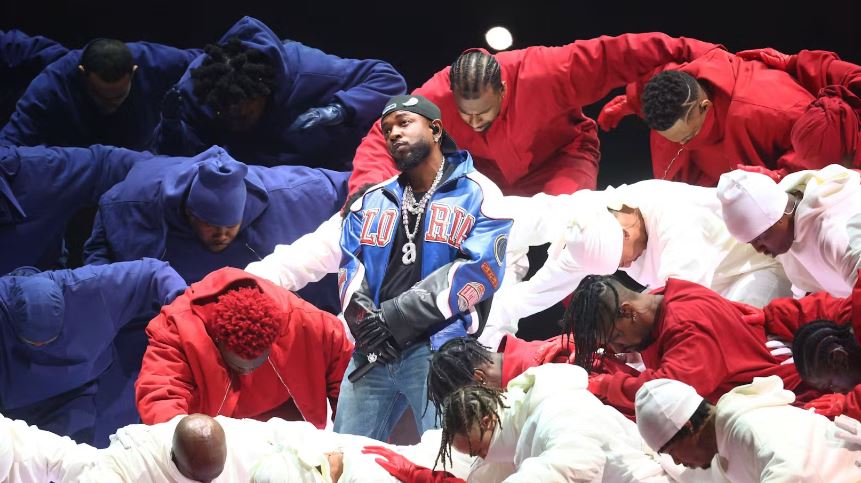

Decades later, the use of music to confront injustice continues. In 2015, Kendrick Lamar released Alright on his third studio album, To Pimp a Butterfly. Where Marvin Gaye imbued his music with jazz to protest war, and Stevie Wonder used funk to criticise the misuse of political power, Kendrick turned to hip-hop. His message was clear, that black suffering had not disappeared. Police brutality, institutionalised racism, and unequal opportunities continue to shape black lives into ones premeditated by injustice within America. Though Lamar’s message is driven by pain, the motif ‘we gon’ be alright’ is one of optimism. During the Black Lives Matter campaigns, Kendrick Lamar’s chorus became an anthem of hope and reassurance which promised a better future, one without inequality. At the 2015 BET awards, Kendrick performed the track on top of a police car, a powerful image that confronted police brutality head-on.

If it’s art and media that are so consistently consumed, then they can be used to confront and expose the injustices which linger

In 2018, Childish Gambino released the widely acclaimed single, This is America. The track pairs uneasy melodies while discussing harsh topics such as gun violence and cultural distraction. The accompanying music video, directed by Hiro Murai, shows Glover dancing erratically, seemingly oblivious to the chaos erupting behind him. His movements overtly resemble the minstrel show character, Jim Crow, who was one among a cast of stereotypical depictions of Africans through demeaning caricatures. These movements distract the viewer from the background reality on purpose, making the claim that, in the same way, the media distract the public from the everyday realities of America. The music video references the Charleston church shooting, police brutality, and riots. The video’s closing scene, where Glover frantically runs from a pursuing mob, serves as a metaphor that ignoring or denying systemic injustice and national issues can lead to further destruction.

From the ’70s to the modern day, violence and injustice continue to fracture society. Such violence may appear on the news and achieve only a mere thought by its viewers, with no action taken. But if it’s art and media that are so consistently consumed, then they can be used to confront and expose the injustices which linger. Where these issues go unheard, music can raise its voice and allow it to echo through the streets.

Comments