An exhibition of history and progression: A Different View at Leamington Spa Art Gallery

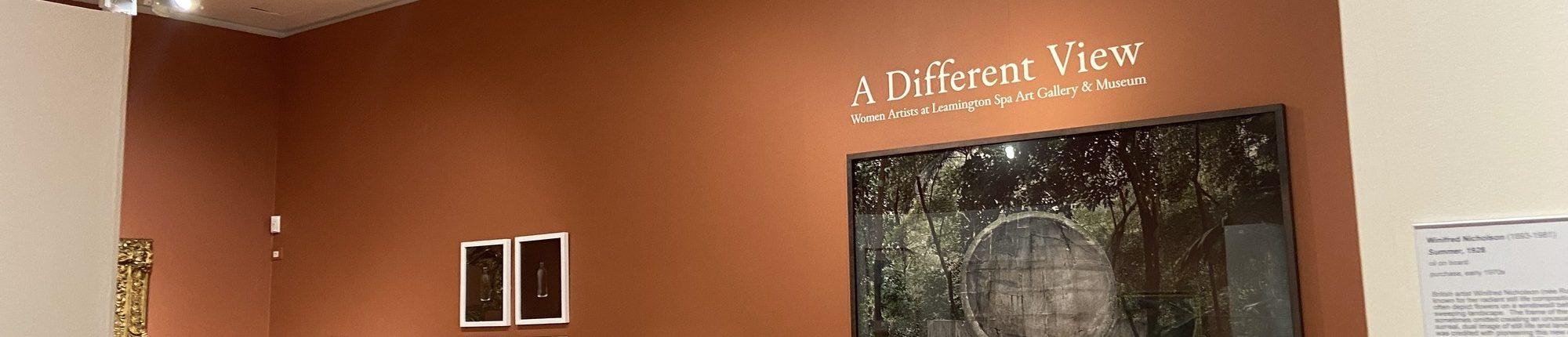

Entering Leamington Spa Art Gallery’s new exhibition, A Different View: Women Artists in the Collection, you’ll be met by the varied works of over 50 British women artists. Curated together with a desire to restructure women’s historical absence from the art world, the exhibition bridges together artists from the late Victorian period to the present, tracing women’s complex, quiet, and winding road to the gallery wall.

Although the exhibition is fairly modest in size, its context is necessarily expansive and acts as a kind of directive thread. The sculptures, paintings, and photographs on display are, despite their engagement with many diverse themes, located together under a singular idea of female artistic practice. At times, the exhibition’s mix of disparate artworks seems unfocused, draping the encompassing banner of woman artist over its sometimes incoherent curation choices. But the idea of the woman artist, her hidden history and struggle for artistic recognition, is – in the show’s firm handling of context – spelt out as entirely necessary. What draws us to the artworks in the room is perhaps the questionable allure of this mysteriously quiet and suppressed history. A history that itself designates having to use the term ‘women artists’ in the first place.

It is a show that truly wears its intentions on its sleeve, wanting to shift away from the past of male-dominated artistry, knowing that any evaluation of art history would be incomplete without the women adorning its edges

Looking to a central bench in the gallery, you’ll find supplementary reading that truly encapsulates the exhibition’s feminist tone: The Story of Art Without Men by Katy Hessel, Nineteenth-Century Women Artists by Caroline Chapman, and Linda Nochlin’s seminal work Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? It is a show that truly wears its intentions on its sleeve, wanting to shift away from the past of male-dominated artistry, knowing that any evaluation of art history would be incomplete without the women adorning its edges.

There is an easy demand made for viewers to engage with this context: turn one corner and remember educational barriers against women – how the Royal Academy School dismissed women until 1860. Turn another and remember how, presently, The National Gallery holds only 2% of works by female artists in its collection. Almost every piece in the exhibition uses its label to share a gentle reminder of the impact that social institutions had on these women’s lives and work.

Indeed, the majority of artists here clearly benefitted from the education they received, putting aside admission refusals like Lucy Kemp Welch’s from the Royal Academy. Many women featured (such as Nan Youngman, Tessa Beaver and Mary Duncan) attended the Slade School of Fine Art, which broke new ground in 1871 when it opened to male and female students with fairly equal requirements. Other late 19th and early 20th century artists on display were freshly unbarred from nude life drawing classes, joined up with the women’s suffrage movement, or were members of The Royal Society of Women Artists.

Among this sense of gendered progression in the exhibition, the great thematic variations in the works chosen lead to some undoubtedly compelling, thoughtful moments. Death and life are considered. Explorations in medicine sit nearby depictions of urbanity, the natural world, and space. One half of the room is dominated by the body – understood both biologically and as a thing primed, painted, and gazed upon. Here, all the archaic, artistic conservatism falls and, so obviously, the works show how women artists have been just as intelligent, just as clearly descendants of the old masters as their counterparts … when given the opportunity to prove it.

This dialogue between the old and the new, spanning changing art world circumstances, is a true highlight of the exhibition

Alongside works from the 19th and 20th centuries, the presence of contemporary artists within the exhibition shifts its angle toward the future. This dialogue between the old and the new, spanning changing art world circumstances, is a true highlight of the exhibition.

In one corner, Lou Blakeway’s 2023 piece, titled Rape Culture, depicts femininity and subtle violence in a mythological scene of women. Painted in loose strokes of oil, the painting makes reference to Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus and Primavera in its composition, as well as being suffused with imagery of Greco-Roman mythology, such as laurel wreaths, a swan, and a minotaur’s head. Nearby, the gorgeous hues and gentle brush marks of early 20th century impressionistic portraits, and the technical mastery of Early Renaissance reproductions, are reconsidered next to the context of Blakeway’s contemporary piece. Blakeway’s painting reminds us that – from Greco-Roman damsels, to Victorian women confined in their domestic interiors – one cannot look at figurative pieces with an innocent eye: portraits of women and their bodies are full of deeper social implications, having been afflicted with an objectifying gaze throughout art history.

The texture and mark-making in [Mary Riley’s] pieces Lake I and Lake II find the aquatic world to be a nurturing, impressive and feminine space

Vanessa Bell’s presence in the exhibition is also a highlight, bringing with it the coterie of the Bloomsbury Group and a taste of female, modernist practice. Used on the show’s promotional material, her 1928 painting, A Venetian Window, uses the window as a compositional device to split the painting between interior and exterior, daily, city life. However, the painting’s focal point is decidedly natural: beautiful, bulbous flowers sit atop spindly stems in a glass vase. Other pieces on display render nature in far more abstract ways, and, often, something distinctly feminine is found in contact with the earth. Mary Riley’s contemporary work chimes with this idea, as the texture and mark-making in her pieces, Lake I and Lake II, find the aquatic world to be a nurturing, impressive, and feminine space.

Many of the works on show for A Different View are affecting – not only for their range of subtle and grand visual language, but also for the layered history that made them. Free to visit and open until 5 October, if you find yourself in the Leamington area with an itch for art and an hour to spare, this exhibition is certainly worth seeing.

Comments (1)

We always talk about women in STEM but never enough about the women in the arts!!! Important and informative article 🙌