‘They just took it, and then they will just say it’s theirs’: Anna Andruseiko on reclaiming Ukrainian cultural heritage

Anna Andruseiko is 23 years old, from Stryi – a small tower in western Ukraine – and has a degree in cultural studies from the Ukrainian Catholic University (UCU). I had the privilege of interviewing her on life in Ukraine both before and after the full-scale invasion and her hopes for the future which can be read here.

A lot of Brits only know about Ukraine in the context of the war, something I am also guilty of, so I also wanted to learn more about the arts in Ukraine. Anna is deeply passionate about Ukrainian culture having written her thesis on Ukrainian identity and food culture and was excited to delve into this topic with me.

She first explained that Ukraine is currently undergoing a complex decolonisation process with many key cultural figures misrepresented as Russian. Anna recommended a book titled Decolonising Art. Beyond the Obvious. Written in both English and Ukrainian, it explores Ukrainian artists’ roots and how Ukrainians try or actually manage to decolonize them.

Even in the UK, a lot of museums label pieces as Russian when they are in fact Ukrainian

“Russia stole so many things from Ukrainian culture, and that’s what they do,” said Anna. “In one part of Kherson, they went to this library which had unique artefacts from a Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko. They just took it, and then they will just say it’s theirs.” Even in the UK, a lot of museums label pieces as Russian when they are in fact Ukrainian.

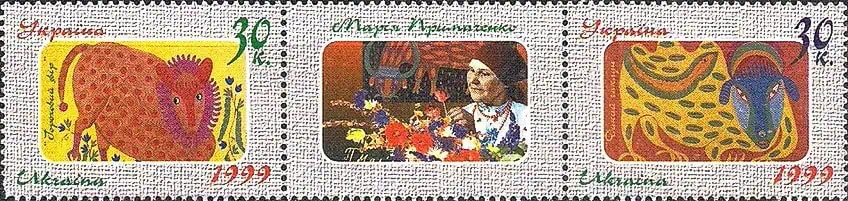

Anna spoke passionately about one of her favourite artists Maria Prymachenko whose works inspired Picasso. “Her works are part of the naïve art movement,” Anna informed me, “and in Ukrainian, they have really childish names as a child can create the name for things that never existed which sometimes adults cannot grasp it or cannot create it because our fantasy is not the same as when we were children.” Some people in Ukraine don’t even know about her and her museum. Eager to learn more about her works, Anna sadly told me that the museum showcasing her works was bombed. “It was bombed by Russia and the art that we managed to save was portrayed in several exhibitions around Ukraine. However, it’s a common problem now that lots of Ukrainian museums just hide their collections and you can’t see them because they can be bombed any day.”

“Russia has also changed people’s names declaring you cannot belong to something else, except the Soviet Union”

“Russia has also changed people’s names declaring you cannot belong to something else, except the Soviet Union,” Anna told me. There is the Ukrainian Armenian filmmaker, Serhii Parajanov, but his Armenian name is Sarkis Hovsepi Parajanyan. So, they changed his name and surname so that he fits into the Russian language.” Anna strongly encouraged me to check out a film he made in 1965 called Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, declaring “it’s an amazing masterpiece”. The effects for the time were groundbreaking and showcased various aspects of Ukrainian culture, including a mountainous area near Anna’s region.

“He is extremely famous around the world, but in most of the museums, all of his works in abstract art, Suprematism, and other movements were considered Russian […]”

Another example of a Ukrainian artist presented as Russian is Kazimir Malevich. “He is extremely famous around the world, but in most of the museums, all of his works in abstract art, Suprematism, and other movements were considered Russian. However, he was born in Kyiv with some Polish roots, but Russia claimed him as Russian.”

Turning to music, Eurovision was a hot topic of discussion which serves as a platform for Ukrainian music to get noticed. “Ukrainians admire Eurovision,” Anna enthusiastically shared. Anna wanted to highlight the work of 2016 winner Jamala. “Her works are like a piece of art. She’s a Crimean Tatar and she speaks a lot about Crimean Tatars and their culture. She has an album called Qirim which is dedicated to Crimean national sounds, and she won several awards for it.” I then learned about electro-folk group Onuka, who performed in the interval at Eurovision in 2017. “They blend the electric sounds with traditional Ukrainian instruments, and that sounds magnificent.”

I was curious if Anna had any suggestions for how we can gain a better understanding of Ukraine’s past and present. If you’re looking for something academic, Anna recommended The Gates of Europe: A History of Ukraine by Serhii Plokhy. She did warn me, though, that it was a very large book and quite heavy going, but it provides a lot of answers about Ukrainian culture.

She also mentioned a project called Ukraїner, who were one of the first to translate their content from Ukrainian to English. Initially set up to show Ukraine to Ukrainians, their mission became broader and sought to show Ukraine to the world. “They have amazing books and articles. There’s one book in English, Ukrainian Insider, which discusses the traditions of specific regions, supported by pictures of people and their stories. It is a very light and easy-to-read book and still provides a lot of information,” explained Anna. “They have also a new book, De-occupied: Stories of Ukrainian Resistance. It is a reportage collection based on Ukraïner‘s expeditions to the territories of Ukraine liberated from Russian occupation in April-November 2022.”

It’s important to appreciate and recognise the vast contribution by Ukraine to the arts

For those of you wanting to learn more about Ukrainian history and culture, Anna shared this link from her university with a valuable list of resources. Ukrainian culture and traditions are incredibly rich and diverse – now more than ever, it’s important to appreciate and recognise the vast contribution by Ukraine to the arts.

Comments