Cyn review: An ode to community in the face of an uncaring government

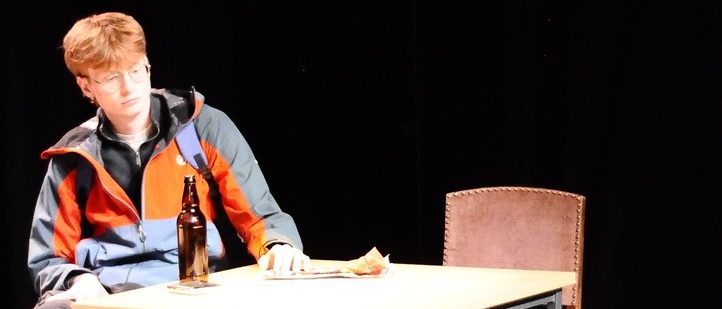

A wealthy English man walks into a pub in rural Wales. You’d be forgiven for thinking this is the start to a joke but rather, this is the set-up to Sam Rees’ Cyn – a moving portrait of Welsh working-class identity in the mid-90s. A chamber piece, Cyn’s story unfurls within the walls of a small, run-down pub somewhere in Wales where an Englishman, Simon (Charlie Muskett), seeks refuge after he runs out of petrol. Inside, he meets Emyr (Sam Rees), a curt and unfriendly Welsh man who frequents the bar. At first, Cyn appears like a fish-out-of-water comedy with a frazzled Brit subjected to various jokes at his expense due to his complete inability to blend in. However, Cyn has even more going for it, soon developing into a discussion of prejudice, protest, Thatcherism, family and community as Simon discovers the ramifications of the mid-80s miners’ strike on this small town.

The relationship Cyn has to the real-life events that inspired it is perhaps its secret weapon, able to supply great emotional weight through the knowledge that those behind the play possess a personal connection

From this description, Cyn may sound tonally jarring, but Sam Rees’ play is far from it, balancing the two, at times oppositional, tones wonderfully. Paired with Seren Davies’ direction, Cyn unites political commentary and humour through a raw, honest, and authentic portrayal of its subject matter. The relationship Cyn has to the real-life events that inspired it is perhaps its secret weapon, able to supply great emotional weight through the knowledge that those behind the play possess a personal connection. This is established before the play even begins with home video footage of some of the crew’s relatives speaking about the miners’ strike as the audience settles in. This immediate establishment of a personal relationship to the material helps lay the foundations upon which the play builds.

First and foremost, Cyn is a play about community, seeking to create a sense of temporary community among the audience with each performance. This is cultivated most effectively through the creation of a lively atmosphere through the play’s many musical sequences. With performances directed by Jed Kain (who also plays guitar and sings in them), Cyn’s moments of music are deliberate and effective, designed to draw the audience into the world of the story. This is aided by the play’s interactive elements where the audience, armed with lyrics in the programme, are encouraged to sing along to the Welsh folk songs being performed. These moments are where things feel most communal as a room of relatively shy participants gradually grows in volume, urged on by the cast as well as one another. Backed by a trio of talented musicians (Kain on guitar, Ethan Delcroix on trumpet, and Caitlyn Bailey on cello) and led by Rees or Kain, practically everyone in the room was singing by the songs’ last choruses. Far from feeling like a church service, these moments of song are positioned as emotional outbursts. They express a whole spectrum of feeling whether this be joy, anger, or sadness, involving the audience in each moment of catharsis. Whilst these moments of song seemed daunting to me at first (I’m not one for audience interaction), they became some of the most memorable parts of experiencing Cyn, creating a rousing and lively atmosphere akin to a bustling pub rather than a drama studio.

Anger feels particularly potent as there is a thrumming rage beneath Cyn’s surface. Rage at a government that can so easily disregard and damage small communities before walking away unscathed

This lively atmosphere also stems from the committed performers on stage and their proficiency in comedy. Rees and Muskett play off one another wonderfully, particularly in the early, deeply awkward interactions between Simon and Emyr. Muskett has the bumbling Brit archetype down whilst Rees’ deadpan delivery never failed to produce a laugh from the audience. The inclusion of the oftentimes off-screen owner of the pub, Mary (played by director Davies), shouting down to the pair and the sleepy, grumbling regular Alun (Jed Kain) also went a long way in producing humour in the early scenes. These performers are not just one-trick ponies though, displaying an ability to tackle more serious, emotional scenes. Rees is given the most moving moments, and he delivers them admirably, playing multiple emotional states excellently. The performances in Cyn make investment with the characters easy, making the emotional moments hit even harder for the audience. When Emyr reveals what happened to the village in the 10 years after the strike and closure of the mine, the whole room feels the impact – the sadness, the desperation, and the anger. Anger feels particularly potent as there is a thrumming rage beneath Cyn’s surface. Rage at a government that can so easily disregard and damage small communities before walking away unscathed.

When engaging in such important political discussions, there can be a tendency for characters to become allegorical figures rather than fleshed-out characters. Whilst Cyn almost falls into this trap, the writing is strong enough to keep these characters as defined individuals. For the most part, they are nuanced figures with complicated emotions, able to embody wider themes whilst remaining strong characters themselves. This makes for even better drama as Cyn can tackle important issues (a vital necessity for the arts) whilst retaining personal and emotional stakes within these more abstract ideas. Out of the two leads, Simon is perhaps slightly less complex than Emyr, but as the audience surrogate of the pair, this makes sense. Even Mary, who I was worried was going to simply be the ‘nagging woman’ archetype, is allowed moments of emotional complexity, displaying her role in this community outside of her comic moments.

With this being said, the closing moments almost entirely make up for these issues, delivering pure emotional power that is undeniably affecting

Practically the only time Cyn falters is in its pacing. By no means a poorly paced play, there are just moments when the drama can feel slightly repetitive as characters recite monologues to one another. As beautifully written and performed as these moments are, they don’t always feel like natural, free-flowing conversations between characters, hurting the rhythm of the play as well as, at times, breaking the immersion that has been so impeccably crafted. These can be felt the most as the play nears its final third. With this being said, the closing moments almost entirely make up for these issues, delivering pure emotional power that is undeniably affecting. Frankly, Cyn’s final few scenes are spellbinding.

As dynamic and fun as it is emotional, Cyn is a real highlight of theatre at Warwick University. Comprised of talent on and off the stage, Cyn deals with important issues with humour, sadness, and rage, allowing the audience to share in all of these. Whilst it runs into some pacing issues in its middle section, the confidence and ability of the performers, Rees’ writing, and Davies’ direction more than make up for this, producing a play that stays with the audience long after the curtain falls. With the team planning to take Cyn up to the Edinburgh Fringe at the end of August, I feel certain they will not have difficulty in drawing a crowd – this is not one to be missed.

Comments (1)

Why in the discussions regarding the mining strikes up and down the country is there no mention of the damage done by the Unions, encouring the strikes making the mines uneconomical to run and virtually holding the country to ransom. I lived through it and remember the electric going off trying to save fuel. Under Ted Heath. Thatcher inherited the problem and called Scargills bluff, hence mining closures sadly to effect lots of communities.