Poetry by the algorithm: is Instagram poetry any good?

Instagram poetry can also be known by its shortened form, ‘Instapoetry’, which is possibly a more accurate name for the phenomenon. Its poems are typically characterised by a lack of punctuation, short lines and stanzas, and simple language. Appealing due to its bite-sized format, Instapoetry is perhaps the most common and visible poetry format in the 21st century.

In the literary world, Instapoetry is hotly debated: is it good or is it bad? Because ‘good’ and ‘bad’ are largely subjective descriptors, perhaps the debate is less interesting than considering the environment surrounding Instapoetry that fostered its creation and popularity. Is Instapoetry just the genre’s evolution, necessary to ensure its survival in a hyperactive, online world, or is it just a symbol of lazy capitalism?

Poetry has long been an art form, though it has rarely made careers – at least not like it can now

“Don’t quit your day job”, “don’t put all your eggs in one basket”, “what’s Plan B?” are some phrases I imagine were thrown at some of the world’s most renowned poets. William Blake (Songs of Innocence and Experience) is today known as both a poet and a painter, but whilst he was alive, he earned his keep as an illustrator, drawing teacher and engraving for book publishers. William Carlos Williams (‘The Red Wheelbarrow’) was a practising doctor and Pablo Neruda was a diplomat. Robert Burns was a tax collector and a farmer. Sylvia Plath took on a job as a receptionist and T.S. Eliot worked in LLoyds Bank before moving to publishing.

Poetry has long been an art form, though it has rarely made careers – at least not like it can now. “No way poetry can pay your rent”, believed Rupi Kaur, perhaps the first name to your mind on hearing ‘Instagram poet’. That was until her career skyrocketed, sending her on a world tour with the release of her first poetry collection, milk and honey, appearing on Jimmy Fallon, selling 2.5 million copies of the collection and outselling Homer back in 2016, according to The Atlantic.

Does Instapoetry care about the art of literature, or is it just a vehicle to lazily turn the capitalist’s wheel?

The collection, and others like it, has provided poetry with what the Economist calls an “alarming” rise in sales. A popular strand of argument maintains that Instapoetry is branding and good marketing, not quite an art form – a “huckster’s paradise” was how the headline of Claire Fallon’s 2018 Huffington Post article described Instagram poetry.

This seems to be where the debate largely lies. Does Instapoetry care about the art of literature, or is it just a vehicle to lazily turn the capitalist’s wheel? Saying that, is there a way to publish writing without simply turning the wheel? Perhaps Instapoetry is poetry’s survivalist response to a world where the percentage of adults who read for pleasure is dropping, and 40% of Britons have not read a book in a year, says The Guardian.

In 2010, Chad Harbach, famously wrote that there were two distinct literary cultures in the USA. On the one hand, there is the institutional and university-based canon, and on the other, the world of New York-based publishing. We can extend these two cultures to the wider Western world, as well as Faith Hill and Karen Yuan’s outline of an emerging third culture: “the fast-paced, democratizing, hyper-connected culture of the internet”.

with the inevitable rise of the internet and its integration into everyday life, we can only hope that Instapoetry serves as a nurturing introduction into the world of poetry and wider literature, encouraging its readers to investigate further.

Indeed, there is an increasingly difficult-to-ignore literary culture forming online, popularised on TikTok, in what is often dubbed ‘BookTok’. The works associated with this genre tend to cater towards young adults, a lot featuring romance plots that are often quite explicit. On the literary totem pole, this third, social media-centric culture often falls to the bottom, raising sceptical eyebrows and largely deemed ‘low-brow’.

Kazim Ali, a practising poet, says he’s “mildly annoyed” that the years he’s spent studying and building on the longstanding poetic tradition when all it seems to take to become a famous poet are “some superficial musings, some pretty okay (honestly) drawings, and one (admitted awesome) photo”. It is perhaps a shame that the young world’s exposure to poetry will likely come from Instapoets who are not especially attached to the craft, or the study of poetry.

Then again, it’s also a shame when British schoolchildren around the country get introduced to poetry through their GCSE anthology, dislike it and from there on, and never go anywhere near poetry again. English Literature students may sing the praises of Keats and Shelley, but Rupi Kaur, Donna Ashworth, and others like them are ultimately far more accessible and arguably better introductions to the world of poetry, at least for the GCSE students of the world.

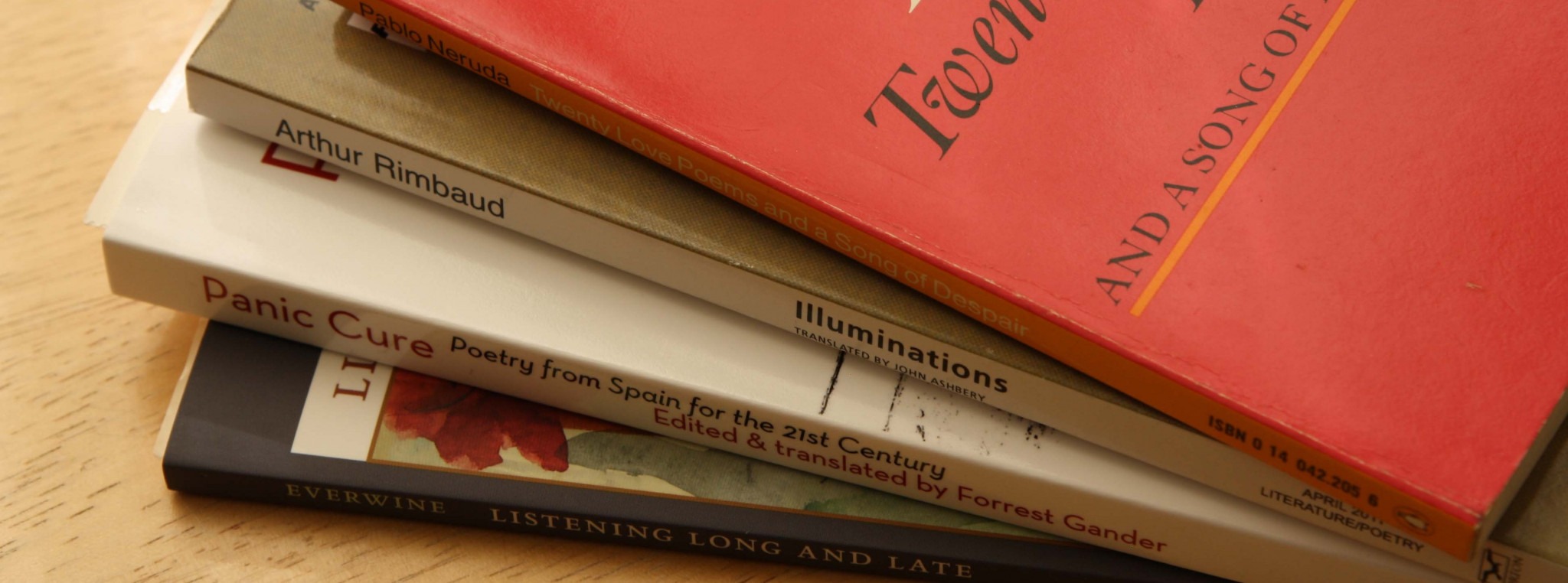

If literature is supposed to be a high-brow, inaccessible world, then we should shun Instagram poetry. But with the inevitable rise of the internet and its integration into everyday life, we can only hope that Instapoetry serves as a nurturing introduction into the world of poetry and wider literature, encouraging its readers to investigate further. There’s a rich, rich world of poetry beyond Instagram, and if we treat Instapoetry as a stepping stone without entirely shunning it, the rest of the world can explore literature and poetry without intimidation.

Comments