Venturing back into Twin Peaks: A retrospective

“It is happening again,” utters the Giant in his eerie omen to Dale Cooper. However, the Giant’s now-iconic dialogue not only reflects the narrative events of Twin Peaks repeating themselves, but speaks to the way in which the events of Twin Peaks continue to impress themselves upon the cultural consciousness. This article is proof of that. While the programme may have firmly cemented itself in the cultural mainstream of 1990, Twin Peaks has transcended time and continues to resonate now just as much as it did 35 years ago.

I first ventured into Twin Peaks not six months ago – eager to further explore the works of the late great David Lynch, I decided to delve into arguably his most famous cultural offering: the brainchild of his work with Mark Frost. Lynch’s work is characterised by its surreal style and thereby a rather equivocal nature, yet it is always tonally defined by blending beauty and deprivation. The archetypal “dead girl” that Lynch cites as the primary inspiration for Twin Peaks – ultimately becoming Laura Palmer – typifies the theme of duality; the first shot viewers receive of Palmer is one that conventionally encompasses beauty, yet Lynch gradually teases out the horrifying circumstances that led to Laura’s murder. Angelo Badalamenti’s soundtrack is similarly reflective of Lynch’s vision; his tranquil opening theme is ultimately subverted by the haunting, mournful tones of the theme of Laura Palmer. Beauty and horror. Good and evil. The White Lodge and Black Lodge. Lynch, despite the incomprehensibility that many viewers attribute to his work, is an ironically honest filmmaker in exploring both the good and bad in the world. And so, following this opening five minutes of Twin Peaks, I knew that I was watching something special; within just five minutes, Twin Peaks bedazzles and haunts its audience.

It has a unique ability to produce a profound milieu of emotion

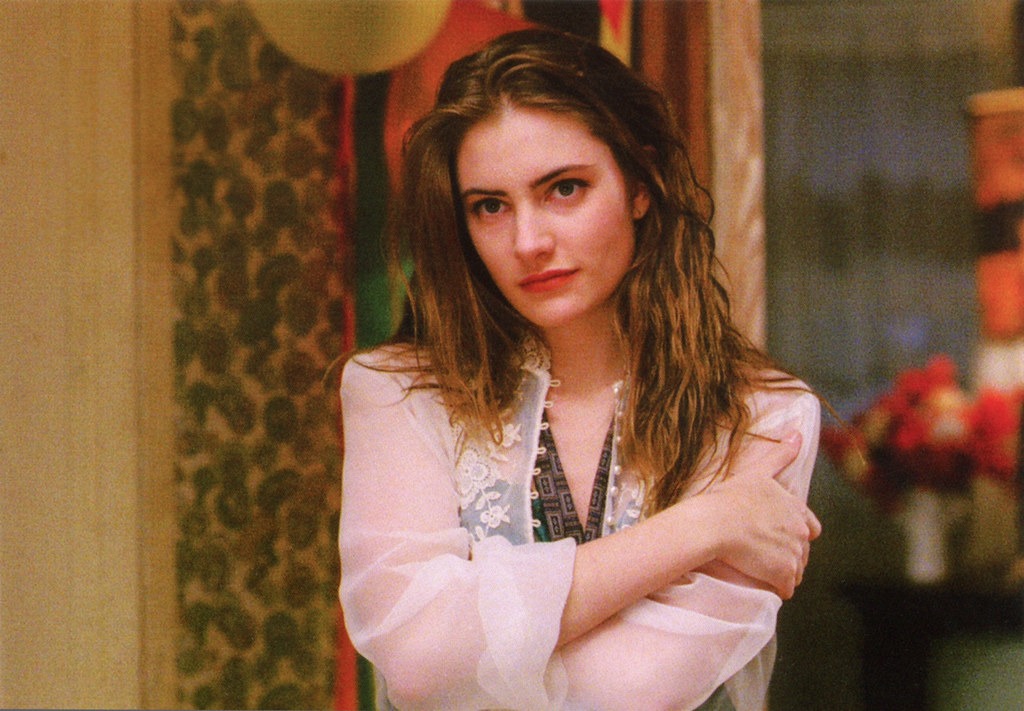

Beyond its unique tonal vision, Twin Peaks is fondly remembered for its roster of characters. First and foremost is Special Agent Dale Cooper of the FBI (Kyle MacLachlan); charming yet firm, Cooper provides the programme’s anchor of reassurance. At a screening I attended recently for Fire Walk With Me, the 1992 prequel film to Twin Peaks, gentle applause was granted to MacLachlan’s credit – his enduring popularity is undeniable. So much of Twin Peaks’s strength is also produced by the quality of its performances; in particular, two that always stand out to me are those of Ray Wise and Richard Beymer, as Leland Palmer and Benjamin Horne respectively. They’re two of the programme’s most despicable characters, yet both actors are mesmerically attuned to their behaviours. Indeed, marrying with the programme’s tone, the finale to season two provides horrifying cliffhanger endings for many of the more moralistic characters; fan favourite Audrey seemingly dead, Cooper’s love interest, Annie, in a coma, and Cooper himself trapped inside the hellish Black Lodge. As the programme’s tone highlights, there is both good and evil in its world, and the characters – much like us – must experience both in equal measure.

However, what really makes Twin Peaks blossom – for me, at least – is its surrealism. Beyond roughly introducing the serialised narrative to modern television, Twin Peaks is foundational in pushing a more artistically imaginative vision upon a mainstream international audience. Lynch had directed several surrealist feature films before his work on Twin Peaks, yet none of them quite achieved the level of recognition of Twin Peaks – it is a surrealist phenomenon that captured the imaginations of ordinary people with conventional tastes. One sequence in particular that is frequently praised with regards to the programme’s surrealism is Cooper’s dream sequence in the memorable Red Room. With the black-and-white chevroned flooring underpinning the programme’s theme of duality, Cooper encounters the Man From Another Place and the apparently deceased Laura Palmer. Does any of this make sense? No. Does it really by the end of the series? No. And yet, it works. Twin Peaks – like many of Lynch’s films – doesn’t necessarily make sense, yet it has a unique ability to produce a profound milieu of emotion.

Twin Peaks remains the bastion of television that it was 35 years ago

While Twin Peaks was cancelled after two seasons in 1991, its persisting impact cannot be understated. Not only is the finale to its second season one of the most dread-inducing televisual experiences out there – with Cooper’s odyssey back to the Red Room ending in one of the most memorable cliffhangers in all fiction – but this finale was swiftly followed by the aforementioned 1992 feature film Fire Walk With Me. The implicit praise I levelled at it earlier really doesn’t do FWWM justice; it is a one-of-a-kind cinematic experience that truly reshapes the impression of Twin Peaks and its inhabitants that the original series presents. And, 26 years after Cooper first drove into the town that is now lodged in television’s hall of fame, Twin Peaks: The Return aired. To call The Return a continuation of the original programme would be an objective fact, yet it feels false. While Twin Peaks once had an explicit narrative to thread its episodes together, The Return is pervaded by an anarchic tone of fragility; nothing feels connected anymore, and the world that we once knew is awfully lonely.

In short, Twin Peaks remains the bastion of television that it was 35 years ago. While those watching might not have realised it, television as they knew it was being reshaped before their eyes. That being said, no one element of Twin Peaks is what makes it such an innovative piece of television; a combination of clashing tones, stellar performances, and some frankly extraordinary ideas creates one of television’s most iconic worlds.

Comments