Ecocide and neo-colonialism: Is environmental change a colonial weapon?

Colonialism has long been understood as a force of political and economic domination, but today, well into the first quarter of the 21st century, its ecological impacts are proving just as profound. The large-scale extraction of natural resources, land dispossession, and environmental destruction have been intrinsic to colonial expansion, shaping the landscapes and livelihoods of the colonised. Far from being a shadow of history, this dynamic persists today under different guises of neo-colonial resource exploitation, corporate land grabs, and the environmental devastation disproportionality inflicted upon the Global South.

Ecocide – the large-scale destruction of ecosystems – is emerging not just as an ecological crisis, but as a tool of modern imperialism, driven by the political and economic interests of powerful states and corporations. In a world where climate change accelerates with alarming speed, it is tempting to see environmental depredation as an unfortunate byproduct of modern life. But the reality is more troubling: environmental change is not only the consequence of colonialism – it is a tool of its continuation.

The colonial model of resource exploitation has not disappeared – it has merely evolved

European empires did not just conquer land. They re-engineered landscapes, extracted natural wealth, and forcibly removed indigenous communities under the guise of ‘civilisation’ and ‘progress’, justified through narratives casting indigenous lands as ’empty’ or ‘underutilised’. The rubber plantation of the Belgian Congo, the deforestation of areas of India under British rule, and the draining of Irish bogs by the English were not incidental outcomes of empire – they were violent acts of domination, reordering nature into an engine of imperial wealth.

Environmental devastation was not a side effect of empire – it was its method, and one that is inseparable from human suffering. Forced displacements to make ways for plantations, railways, and mines separated indigenous peoples from their ancestral lands and lives, collapsing ecosystems of knowledge and culture. Today this continues in regions such as the Amazon, where extractive industries displace communities with the backing of global capital. The colonial model of resource exploitation has not disappeared – it has merely evolved.

Nowhere is this more visible than in the global phenomenon of eco-apartheid – the unequal distribution of environmental harm and protection along racial and economic lines. While the wealthiest nations insulate themselves with green technology and clean infrastructure, poorer nations, often former colonies, bear the brunt of rising sea levels, droughts, deforestation, and pollution, despite contributing the least to the crisis.

European and North American companies remain heavily invested in fossil fuel projects in Africa, Latin America and Southeast Asia, ensuring a cycle of dependence and vulnerability. As environmental sociologist Daniel Aldana Cohen notes, cities like Sao Paulo reveal the violence of eco-apartheid: during water shortages, wealthier areas rarely go without, while poorer neighbourhoods are left dry. In Jackson Mississippi, a crumbling water system has created a man-made disaster described as a “dry run for eco-apartheid”. These are not isolated incidents or unfortunate cases of geography – these are systemic failures, rooted in histories of neglect and a legacy of exploitation.

National parks and wildlife reserves, often funded by Western governments and NGOs, are established on land that has been sustainably managed by indigenous peoples for generations

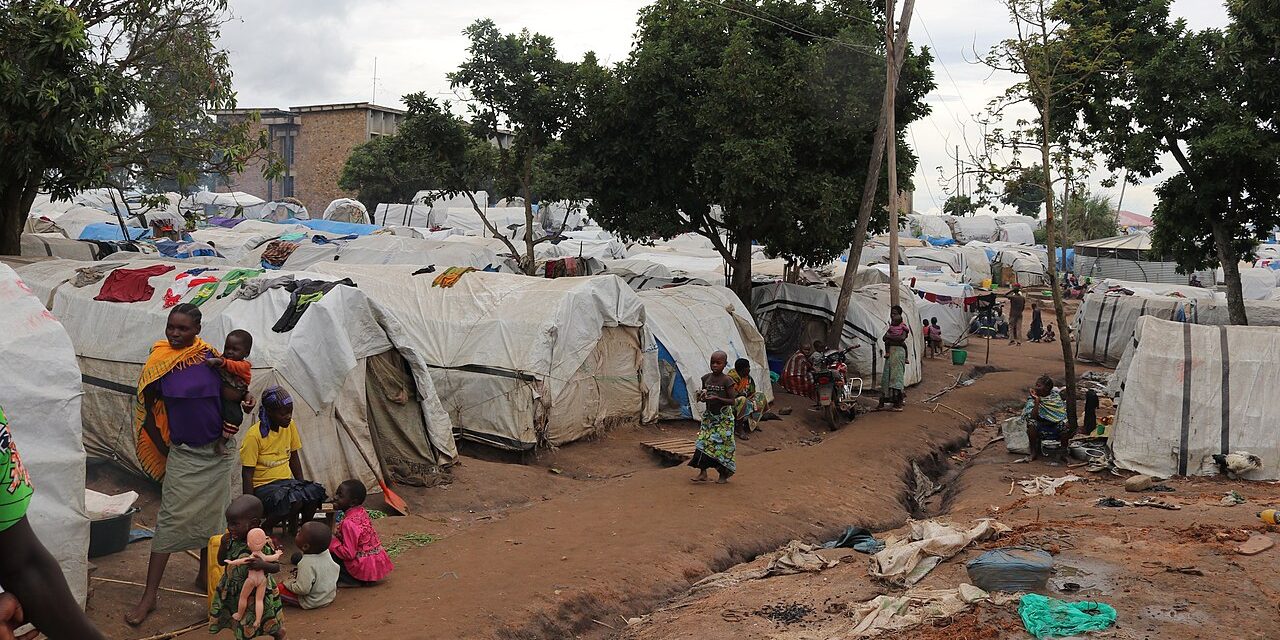

But environmental injustice doesn’t mean unequal exposure to harm – it often results in forced displacement. Since 2008, more than 376 million people have been displaced by climate-related disasters. Behind each number is a loss of home, culture, and belonging. As with all forced migrations, not all refugees are treated equally. While some are granted asylum, others are criminalised and abandoned. The language of “climate refugee” remains legally unrecognised in many international frameworks, rendering millions invisible in the eyes of the law.

Displacement, however, doesn’t always arrive with storms or droughts – it can also come wrapped in the language of protection. Across Africa and Asia, communities are being evicted from their ancestral lands in the name of conservation. National parks and wildlife reserves, often funded by Western governments and NGOs, are established on land that has been sustainably managed by indigenous peoples for generations. This model of ‘fortress conservation’ echoes the colonial past, where land was seized under the guise of ‘improvement’ or ‘management’, erasing traditional stewardship practices in favour of Western models of environmental control. A stark example of this is the displacement of the Maasai people in Tanzania and Kenya, where lands have been turned into safari parks catering to wealthy tourists. While these parks generate significant revenue, little of it benefits the displaced communities, who are left landless and marginalised. The Maasai, like so many other indigenous groups, find themselves in a cruel paradox: they are evicted for the sake of conservation while foreign companies profit from the exploitation of the same landscapes.

Environmental destruction has also long been wielded as weapon of domination. From the Romans salting Carthaginian fields to the US military dropping Agent Orange over Vietnam and Saddam Hussein’s torching of Kuwait’s oil fields, these acts of ecocide not only caused immediate destruction but were designed to create long-term devastation, ensuring that affected populations remain weakened and dependent. Today, similar tactics persist in conflict zones where the targeting of water sources, agricultural land, and forests serve as a stark and horrifying reminder that controlling the environment is a means of controlling the people. It creates waves of climate refugees, further destabilising regions already grappling with political and economic insecurity. The destruction of Palestine’s ecosystems in recent years has prompted renewed calls to classify such acts as ecocide. Nearly half of Gaza’s tree cover and large swathes of farmland have been destroyed, water systems bombed, and waste allowed to pollute entire regions. While the loss of human life rightly dominates headlines, the environmental devastation is no less deliberate, and no less deadly. Ecocide, here, is not a byproduct of war. It is part of its arsenal.

The consequences, though often indirect, consistently fall hardest on communities who are least able to respond

So what does it mean to call ecocide a crime? A growing international movement is pushing for ecocide to be recognised in the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. In 2024, Pacific Island nations – among the most threatened by rising seas – formally petitioned for ecocide to join genocide and war crimes as an international offence. Such recognition would not only enable prosecution, but also force global leaders to confront the environmental violence disproportionately inflicted on the least responsible. Critics might argue that environmental harm is too difficult to attribute to colonial legacy, but this overlooks a critical truth: the consequences, though often indirect, consistently fall hardest on communities who are least able to respond.

If colonialism and ecocide are deeply intertwined, then true climate justice demands more than emissions targets – it requires confronting the historic and ongoing depredation that fuels global inequality. Reparations, land restitution, and indigenous land rights must be central to a climate justice movement. Crucially, those who have long protected their environments – indigenous communities and grassroots movements – must lead the way. From Amazonian forest defenders to African agroecologists, their work offers not just resistance but a blueprint for a more just and sustainable future.

Labelling ecocide a colonial weapon is not a hyperbole – it acknowledges a structural reality in which certain lives and landscapes are systematically devalued for the benefit of others. As Judith Butler writes in Frames of War: When is Life Grievable?, we must interrogate the structures that determine whose suffering is to be acknowledged, and whose is ignored. If some lives are made ungrievable, then some lands, too, are rendered unworthy of protection – at least until they serve the powerful. To challenge ecocide is to confront those structures – to demand justice not as charity, but as historical reckoning. For unless we reckon with the colonial roots of environmental collapse, we risk reproducing the same injustices we claim to dismantle. In the fight for a liveable future, justice is not optional – it is a moral imperative.

Comments