US trade policy: assessing Trump’s tariff strategy

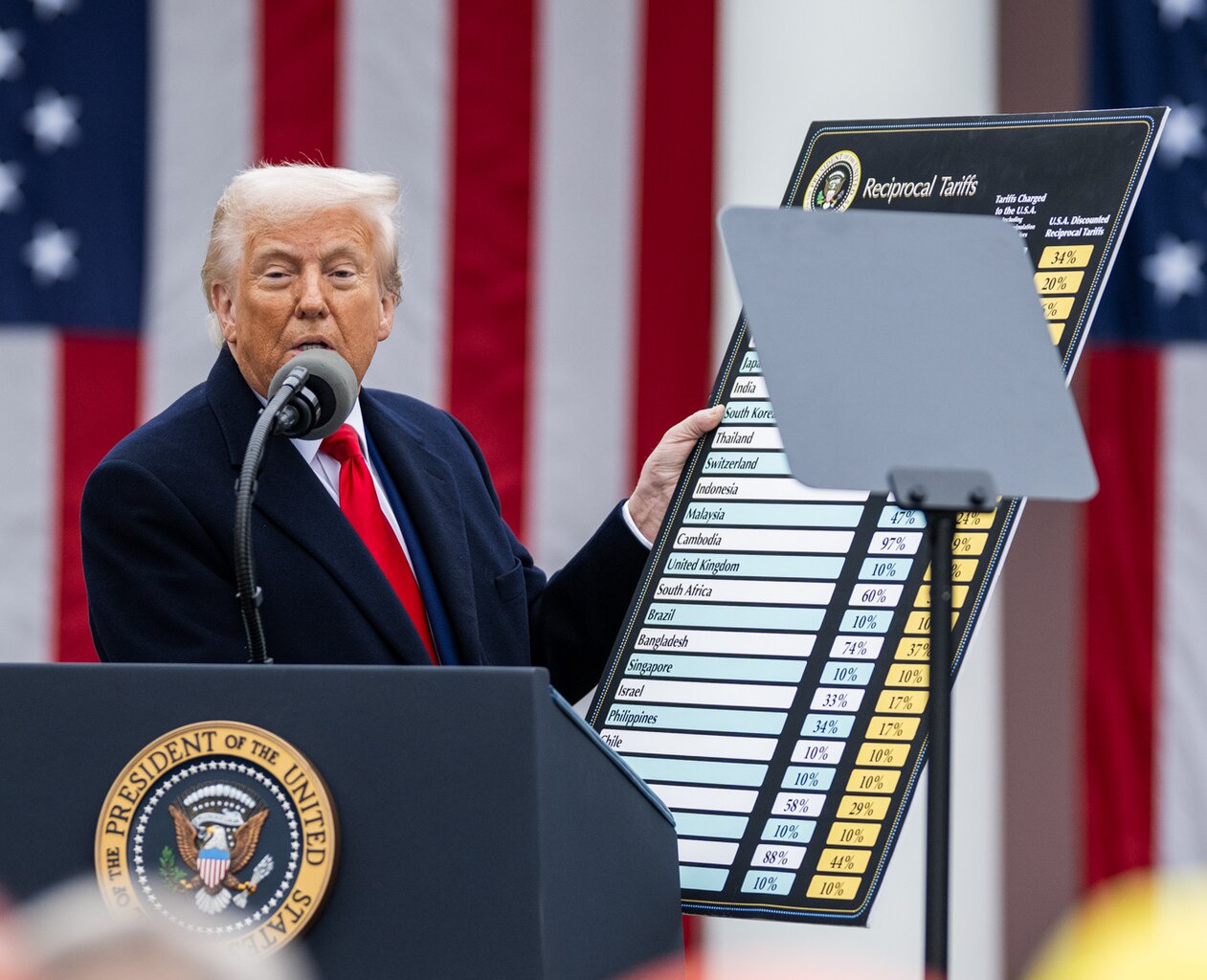

President Donald Trump has unveiled a sweeping new tariff regime: a 10% base tariff on all imports, with higher “reciprocal tariffs” for countries with large trade deficits. He has framed the move as a way to address the large US trade deficit, which he claims has gutted US manufacturing and undermined the nation’s economic and national security. The policy marks the most significant shift to protectionism in the US since the 1930s and will have sweeping impacts, especially in the modern world of globalisation.

Is the shift sound policy, or a recipe for self-inflicted harm?

As of April 2025, Trump has implemented a complex set of tariffs on imports. A universal 10% tariff applies to all goods entering the US but layered on top are several country-specific duties. China faces the harshest penalties, with tariffs reaching 145% following a trade war in which China has retaliated with a 125% tariff on US goods. Canada and Mexico face a 25% tariff on most exports to the US, with Canadian energy products subject to a reduced 10% rate. The European Union has been threatened with a blanket 25% tariff, but specific duties, such as a 200% tariff on alcohol, have already been implemented. Additionally, a global flat rate of 25% now applies to all steel and aluminium imports. The impacts of these tariffs will have extensive implications for both the US economy and international markets.

In 2018, Trump claims to have created 1,000 jobs following his steel tariffs, but in reality, it cost 75,000 jobs in steel-related industries

Following the announcement, the economic outlook plummeted. US equities experienced notable declines, with the S&P 500 dropping approximately 8% and the Nasdaq 100 falling over 10% since the tariffs’ implementation. The likelihood of economic decline also rose: a Reuters poll indicates that the probability of a US recession within the next year has increased to 45%, up from 25% in March. Furthermore, the Penn Wharton Budget Model has projected long-term harm to the US economy. They predicted a 6% loss in GDP and a 5% wage reduction, with the typical middle-income household potentially facing a $22,000 loss. If these projections are correct, low and middle-income households are likely to bear the brunt of the impact, facing a combination of job losses, rising prices, and potentially higher interest rates.

The president describes the immediate market losses as a “transition cost” and assures that, despite “some pain”, the economic benefits will far outweigh the negatives. He says the new tariffs will force trading partners to negotiate favourable terms, revive domestic manufacturing, and generate millions in revenues for the federal government.

It is unlikely that trade protectionism will revive domestic manufacturing, especially if there is a shortage or price rise in raw materials. In 2018, Trump claims to have created 1,000 jobs following his steel tariffs, but in reality, it cost 75,000 jobs in steel-related industries. Furthermore, retaliation from major partners like China only compounds the economic damage, by threatening US exports and supply chains. Far from restoring economic strength, Trump’s tariff policy risks undermining it.

While tariffs may shrink the trade deficit, they do so by making Americans poorer, raising prices, and eroding US competitiveness in critical industries

Trump justifies his hostile trade action as merely “reciprocal”. He argues that foreign nations have aggressed the USA through unfair practices, such as currency manipulation, high import taxes, and other barriers. Whilst he claims the aggression is complex, his formula for “reciprocal tariffs” is simplistic: based largely on the size of the US trade deficit, regardless of underlying economic realities. Ironically, many countries now facing the base 10% tariff import more from the US than they export to it, which raises the question as to whether the policy is targeting the alleged “culprits”.

Trump’s trade policy represents the most dramatic shift towards protectionism since the 1930s and risks major implications for the US and global economies. While tariffs may shrink the trade deficit, they do so by making Americans poorer, raising prices, and eroding US competitiveness in critical industries. The policy is likely to make the US more reliant on its domestic industry but at great costs.

Comments