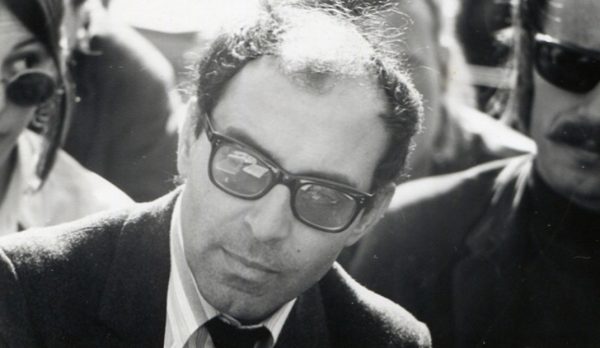

Director Spotlight: Jean-Luc Godard

One of the most common truisms about Jean-Luc Godard’s career is that it ‘changed cinema’. Despite the undeniable truth to this, his body of work is so expansive and radical that there is ideological challenge to all mainstream assumptions about the medium: why and how films should be made, the binary between art and criticism, the morality and future of the medium itself. It is this challenge that makes him as important a filmmaker as has ever lived, and which, even today, leads his work to be marginalised and dismissed by the global entertainment-industrial complex, which determines our cultural horizons.

Godard made his first short films in Geneva in 1954-5, and finished making his final short film the day he checked himself into a Swiss assisted suicide clinic in 2022. However, his most widely recognised films were directed in France in the 1960s, beginning with Breathless (1959) and concluding in 1967 with Two or Three Things I Know About Her, La Chinoise, and Week End.

Godard championed the unique artistic vision in low-brow thrillers, westerns, and comedies

His 1960s films reflect the obsessive cinephilia and eclectic tastes that he developed as a critic at the Parisian film magazine Cahiers du Cinéma in the 1950s. Challenging the binary of ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture, Godard championed the unique artistic vision in low-brow thrillers, westerns, and comedies by Hollywood ‘auteurs’ like Sam Fuller, Howard Hawks, and Jerry Lewis, over France’s more ostensibly serious ‘tradition of quality’. His writing has much film criticism. Such pronouncements as ‘There was theatre (Griffith), poetry (Murnau), painting (Rossellini), dance (Eisenstein), music (Renoir). Henceforward there is cinema. And the cinema is Nicholas Ray’ read more like poetry than the consumer guides to which film commerce reduces the practice of criticism.

Godard’s films are pervaded with a young man’s dynamism and energy – with a sense that films can do anything, to any ends. Breathless is a Hollywood-style thriller pervaded with unmotivated jump-cuts and digressions which range from farce to existentialism; Une Femme est une Femme (1961) was conceived as a musical with no songs; Vivre sa Vie (1962) tells a story in twelve distinct ‘tableaux’, each shot and edited completely differently; Alphaville is a science-fiction film shot cheaply around Parisian modernist buildings, painting a vast panorama of the future on the most economical of canvases.

These films are exuberant declarations of limitless possibility, the triumphant breakthrough of modernism in cinema. The presences of such stars as Anna Karina (Godard’s wife and muse for much of this period), Jean-Paul Belmondo, and Jean-Pierre Léaud, are among the cinema’s most iconic. They move with a rapid pace through many tones and styles, and with a vast cultural and artistic frame of reference, that reflects Godard’s stated desire to encompass everything in his art – a tendency which the great American critic Jonathan Rosenbaum compares to other beloved artists of the time, such as Thomas Pynchon and the Beatles. They are funny, erotic, bitter, devastating, and thrilling – as immediately pleasurable to watch as any films in existence.

However, Godard’s career extends far beyond these masterpieces, and his career extends far beyond them. Although they frequently reference politics, they aren’t ideologically doctrinaire, and they are entertaining enough that they can be enjoyed without thinking too extensively about the cultural and political problems they raise. By 1968, however, Godard was fully radicalised, vocally embracing Marxism and participating in France’s May 1968 protests. He abandoned commercial cinema, and founded the ‘Dziga-Vertov Group’, a leftist filmmaking collective.

Moreover, these are not the films of an incurious fanatic; rather, they are complex and unresolved meditations on what it means to make a political film

That one of the world’s most famous artists would do such a thing is a fundamental challenge to the logic of commercial cinema: that the purpose of filmmaking is to entertain people for money. Godard sacrificed his career to entertain nobody for no money, so it is perhaps inevitable that these films are often dismissed as dull propaganda, and his career subsequent to them is treated as an afterthought. However, time has been kind to the Dziga-Vertov Group films. Godard’s willingness to impoverish himself and destroy his mainstream reputation in order to celebrate (among others) striking French workers, British feminists, Czechoslovakian dissidents, and Palestinian freedom fighters, is admirable on its own terms, at least to me. Moreover, these are not the films of an incurious fanatic; rather, they are complex and unresolved meditations on what it means to make a political film, or rather to ‘make a film politically’, and what one can hope to achieve by doing so.

Over the 1970s, Godard lost hope in cinema’s ability to provoke political change. Meanwhile, he began a relationship with Anne-Marie Miéville, his partner and artistic collaborator for the rest of his life, and returned to his native Switzerland. That most accounts of his career omit its last five decades is a deep shame. His 1980s films reflect his disillusionment, often featuring weary, sometimes mentally ill, middle-aged directors (sometimes played by himself). They wrestle with a pessimistic view that trying to recapture the un-self-aware beauty of classical art – represented in Passion (1982) by a doomed film production shooting live-action recreations of paintings by the Dutch masters – is as futile as creating political art in a commercially compromised medium. Nonetheless, these films are among his most beautiful, pervaded with an appreciation of the natural world that is all the more moving for seeming so incidental.

Later that decade and through the 1990s, Godard made his magnum opus, Histoire(s) duCinéma. Over five hours and eight ‘episodes’, it largely consists of juxtaposed and distorted clips from across film history, photographs, and paintings, with a soundtrack that combines a voiceover by Godard with classical music and songs by Leonard Cohen. Godard’s narration, and the logic of the film’s visual and aural juxtapositions, are often as cryptic as his 1950s writing. Despite engaging earnestly with a range of concrete, troubling themes, the film is both essay and poem, criticism and art – a summation of his career which often plays as a stream of consciousness.

Godard believed that the passivity of the twentieth century’s defining art form in the face of its greatest crime was a permanent moral stain on the medium

If Godard’s meanings are thorny and ambiguous, it’s because he wanted them to be that way: he told Rosenbaum that he wanted people to see him as an aeroplane, a means by which to reach a destination of their own. Nevertheless, there are clear themes running through the film, and through Godard’s other works from the 1990s and this century. His political disillusionment led to a deeper pessimism about cinema’s role in history. His 1960s films are pervaded with an enthusiasm for the medium to capture everything, but in middle age he was haunted by the knowledge that cinema had failed to do so when it mattered: that it had not captured the horrors of the Holocaust. Godard believed that the passivity of the twentieth century’s defining art form in the face of its greatest crime was a permanent moral stain on the medium. His horror at ethnic cleansing in Bosnia and Palestine led him to believe that humanity was already falling short of the hope of ‘Never Again’: that the Holocaust and its lessons were being forgotten, and that cinema was to blame, due to its inability to remind us.

This stark pessimism about cinema, the suggestion that an entire art form is morally compromised, is an essentially unresolvable challenge to anyone who cares about it. However, Godard never truly sank into despair. His career from the 1990s on shows a desire to move forward and discover new audiovisual forms. He was early to embrace the possibilities of digital video, in stark contrast to the nostalgic fetishisation of celluloid in modern film culture. In the 2010s, he experimented with shooting on mobile phones and with 3D. As much as Godard raged against the moral failures of what cinema had been in the past, and against the moral and artistic inadequacy of most mainstream contemporary cinema, the fact he never gave up on the act of making films, and doing so in new ways, shows an unquenchable hope that cinema could become something new, could transform itself for the better.

Godard dismissed Steven Spielberg as ‘not very intelligent’ and denounced Schindler’s List for creating Hollywood entertainment out of the Holocaust: for treating ‘all the Jewish tragedy as if it were a big orchestra’. I’m sure that E.T. would make most people feel much more hopeful than Godard’s brooding late works, but Spielberg’s films have never strayed outside a cinematic language that was nostalgic even in the 1970s; they don’t speak to the present, let alone offer a vision of the future. Godard, by contrast, never stopped searching for new things for cinema to become, and his work is as pressing as ever. He spent the last day of his life making a film. That gives me hope.

Comments