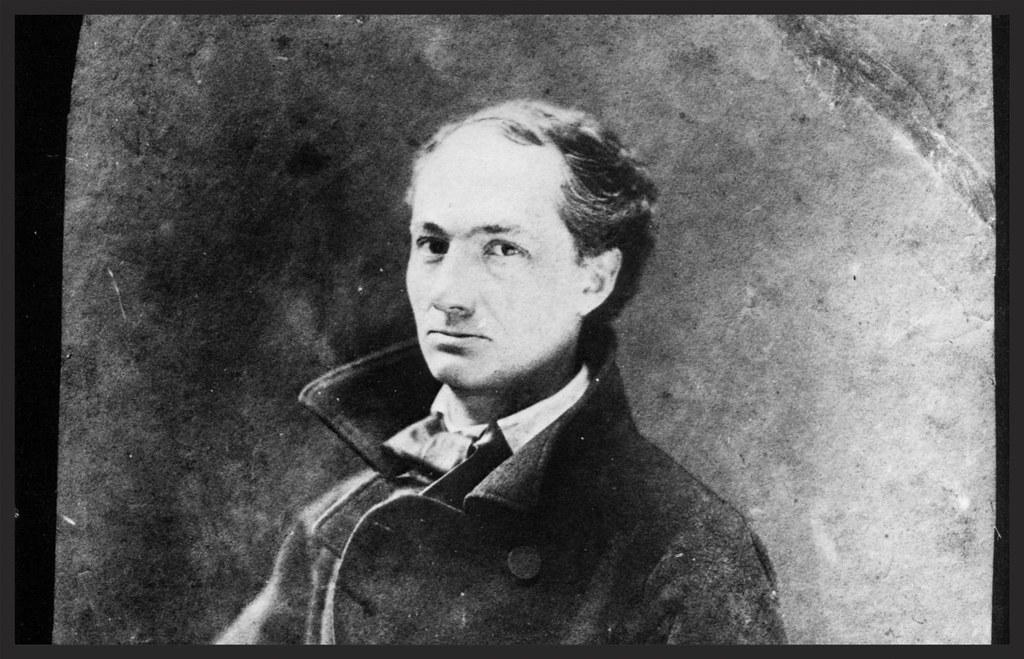

The Poetry Collection: Charles Baudelaire – the beauty and horror of life

Born in the Latin Quarter of Paris 1821, Charles Baudelaire has been declared one of the first modern poets. His connection with the Parisian setting became apparent in his youth. Despite formally studying law, Baudelaire devoted himself to the literary arts and the joys of Paris. His early adult years were a period of intellectual and artistic growth, characterised by extensive volatile relationships, drug abuse, meetings with other writers and artists, attendance of plays and concerts, and visiting bars and brothels. In contrast to his formal upbringing, during his youth, Baudelaire led a bohemian lifestyle.

His first literary accomplishments included his publication in L’Artiste, an illustrated review published in Paris. Most of his publications included literary criticism, fiction and art reviews, in addition to his poetry. Baudelaire drew great inspiration from the works of Edgar Allan Poe, perceiving the American poet as a kindred spirit rather than a mere muse. The remainder of his literary career was dedicated to the composition of his magnum opus – Les Fleurs du mal, as well as his complete translation of Poe’s works. In 1857, Baudelaire published his first edition of Les Fleurs du mal. Within weeks of publication the French Ministry declared it to be “an outrage to public morals”, resulting in Baudelaire and his publisher being sent to trial. Before his death in 1867, Baudelaire had attracted a coterie of admirers, including Paul Verlaine, Arthur Rimbaud, and Stéphane Mallarmé. These names went on to guide the course of late nineteenth-century French poetry.

Best known for his collection Les Fleurs du mal or The Flowers of Evil, Baudelaire’s poetry explores themes of the alienation of the artist, the irrationality of human behaviour, the beauty of evil and the question of modernity. To understand Baudelaire, one must understand the context in which he was writing. During the mid nineteenth-century, Paris endured a period of rapid industrialisation, meaning the city became unrecognisable. This emergence of a new world and new technologies developed a sense of alienation for both the inhabitants of Paris and the artists. With this newness came new values, influencing the artistic landscape of Paris.

Prior to this unfolding modernity, Classicism dominated French poetics – emphasising restraint in emotion, simplicity of style, and traditional form. In the mid nineteenth-century movements like Romanticism, Parnasianism, Decadence, and Symbolism began to emerge, trumping classic forms of poetry. Baudelaire embraced these changes and revolutionised them with his own unique poetic style. In particular, the Symbolist movement resonated with the works of Baudelaire, as it sought to express individual emotional experience through the subtle suggestive use of metaphorical language – a method found repeatedly in Baudelaire’s poetry. Critics and admirers have stated that there is certainly something different about Baudelaire’s imagination – best presented in his collection Les Fleurs du mal.

When I first approached Les Fleurs du mal, I noticed Baudelaire’s certain flair for contrast. By this, I mean that he has a tendency to merge typical ideas of ‘goodness’ with evil. However, what is unique in regards to Baudelaire is that he does not see typical worldly ‘evils’ as something to pity or shy away from, but rather as something to celebrate. This contradiction found laced throughout his poetry is first and foremost evident in the title of the collection: The Flowers of Evil. Traditionally, we do not associate the image of ‘flowers’ with evil. Rather, flowers are a symbol of life, plenty, and beauty. Baudelaire’s celebration of “evil” is shown through the title, since it suggests that something as beautiful as flowers could spring from evil. To note, Baudelaire is writing in a time of great change, revolution, and widening class divides. While indulging in his bohemian lifestyle, Baudelaire is witnessing the contrast between the most vulnerable of the vulnerable, and the most privileged of the privileged. Hence, his blurring of the lines between what is considered good and evil is evident in his poetry – he revels in the horror of everyday Paris. An example of this can be found in his poem ‘Landscape’:

Spring, summer autumn – I will watch them come and go,

and then, when winter drags its unvarying snow,

unsash the drapery, lock up the shutters tight

and build my fairy palaces indoors all night.

There I will dream of pleasure-gardens, blue horizons,

fountains weeping into alabaster basins,

kisses, songbirds at twilight and the break of day,

and Idylls when they most suggest naïveté.

The poet’s juxtaposing semantic fields of grandeur (“drapery … palaces … fountains … alabaster … songbirds”) and underlying sadness (“drags … blue … weeping”) shows the intersection between worldly “good” and “evil” that Baudelaire is crafting. On the surface, the phrase “build my fairy palaces” does not suggest anything sinister, rather eliciting childish notions of fantasy. However, when looking further, the utilitarian verb “build” may be alluding to the current industrial changes that Paris is enduring while Baudelaire is writing.

Moreover, the reference to “fair[ies]” may instead be illustrating this sense of alienation that the Parisians are experiencing, resulting in the need to escape from this rapid and widespread modernity. The final line of this section presents Baudelaire’s use of mockery and humour: “and Idylls when they most suggest naïveté”. The “Idyll” is referring to a short poem celebrating rural and country lifestyles, commonly used by the Romantics. Examples include ‘The Shepherd’ by William Blake and ‘To Autumn’ by John Keats. Here, Baudelaire is mocking the Romantics, or those who do not have a grasp of reality. He is mocking the romanticisation of the everyday and the overall ignorance of the Romantics to the truthful hardness of the world. With Baudelaire, we tend to get a realistic gritty image of Paris, life, and the human condition. He accepts the hardships of life in addition to the beauty and does not see them as two separate entities. With this, Baudelaire transcends the Romantics.

The final stanza of Baudelaire’s poem ‘The Sun’ conveys similar notions of the beauty in the horror of life:

When like a poet, he descends on cities, he

invests even the vilest things with dignity

and, king-like, enters, without retinue or noise,

all of the hospitals, all of the palaces.

The personification of the sun through the third person pronoun “he”, equates the sun with its subjects. The sun is not presented as sublime nor tyrannical – rather the sun is assimilated with the inhabitants of Paris. The simile “like a poet” conveys this equality by likening the sun to Baudelaire himself. Much like Baudelaire, the sun surveys Paris and is unbiased, not afraid to dignify the “vilest” parts of it. In contrast with Romantic depictions, the sun is not idealised here. Once again, Baudelaire does not shy away from truth. The sun is a figure of the mundane, the monotonous, the boring, and Baudelaire shows this by not depicting the sun as some kind of heroic transcendent figure. The final line solidifies Baudelaire’s crafting of the sun: “all of the hospitals, all of the palaces”. This once again demonstrates how, much like the poet himself, the sun reaches and shines a light upon the weakest members of society as well as the seemingly wealthiest. The sun is a quotidian figure, impartial to class and through it, Baudelaire trumps the tyranny that resulted in the Revolution.

Charles Baudelaire “meets the reader boldly, face-to-face, unembarrassed by his flaws and failures.” (Introduction, Les Fleurs du mal) His individual poetic flair sheds light upon the ignored, evil, and sinister parts of the world we live in. Through his drastic contradictions and irony, Baudelaire makes the horrors of life a beautiful thing, worthy of love and celebration.

Comments