The politics within the frame: How do presidential portraits sculpt a persona?

The US presidency has undergone many dramatic overhauls as the country approaches its 250th birthday. Yet, from the first founding fathers, to Trump’s historic non-consecutive terms, one thing has been constant: the presidential portrait. From the manner in which a new president presents himself in the official portrait (I use the masculine here since Americans are yet to vote a woman into office), we can glean much of what the incoming administration’s intended image may be. Implicit in these portraits is a roadmap for the coming four years, notifying the American public of what to expect from their new leader – the world’s new leader.

The power of the still image has proven a crucial tone-setter in the US political scene. Trump’s recent catalogue of defiant photographs, from his death-stare mugshot to his raised fist post-assassination attempt, have only served to embolden his red-cap sporting constituency, and instil in them a unified triumph.

Frozen within the frames, like a time capsule, are their original aspirations for America, along with their varying degrees of introspection or confidence

The predominantly white gallery of presidential portraits captures these men at the moments they assumed office – the most trying time for any world leader. Frozen within the frames, like a time capsule, are their original aspirations for America, along with their varying degrees of introspection or confidence. As such, locking eyes with the intimidating roster of the world’s most powerful men is like gazing into the eyes of history, each portrait crafted and executed according to the world-historical context in which these men first stepped into the hallowed Oval Office.

The first few presidents, including Washington, Adams, and Jefferson, are pictured at their desks, papers in hand, evoking an air of business-as-usual. They appear to be looking up from their writings and momentarily posing for the portraitist (of course, a much more arduous process back then), submerged in the administrative work of ‘founding’ a country. There’s even an impression that they live in the office – the prototypical ‘statesmen’ setting a visual precedent of duty for their successors to follow.

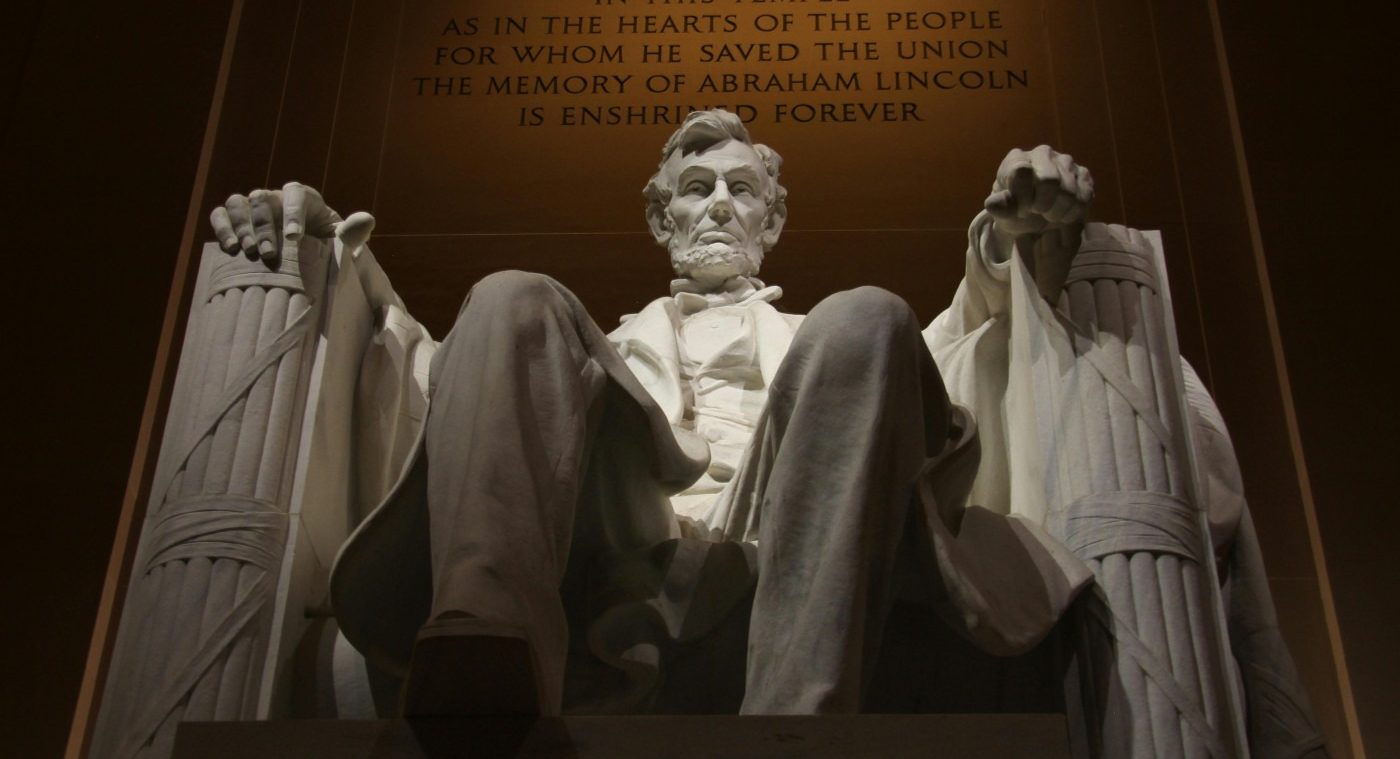

Lincoln’s portrait is arguably the most iconic, oozing confidence and staring head-on down the camera lens

Moving further into the 19th century, the portraits attain a stoicism which belies little of the presidents’ inner natures. Some gaze to the side, while others, like Martin Van Buren, stare at the spectator face-to-face – and startlingly so. Lincoln’s portrait is arguably the most iconic, oozing confidence and staring head-on down the camera lens. Just like the British wartime recruitment poster featuring Lord Kitchener, you cannot escape Lincoln’s stone-cold eye contact, no matter which angle you spectate from.

Leaping into the 20th century, we have the bespectacled Theodore Roosevelt, reader of up to three books per day, and later Woodrow Wilson, the architect of the post-Great War ‘peace’. Proponent of the ‘14 Points’, Wilson’s stern look to the middle-distance connotes a grave understanding of the global precarity at the time he assumed office in 1913, and a willingness to confront the roadblocks ahead. While such an interpretation could be deemed teleological, reading history backwards and impressing the coming war on the face of ‘1913 Wilson’, it is entirely possible that this prevailing international wind would have contributed to the serious image Wilson sculpts in his portrait.

The 1920s was a time of laissez-faire Republicanism, as isolationist post-war politics aimed to remove the US from global affairs. We see this attitude enacted in differing ways between the decade’s three Republican presidents. The intensity of Warren Harding’s smouldering stare, turned to face us directly, underscores a determination to carry America forward at any cost. Coolidge, for his part, is much more reserved, content to continue the decade’s theme of government giving business free rein, and, to put it simply, of ‘seeing what happens’.

The 1960s presidents return to a more hardened, graver image of the presidency, in a decade which would see the Cuban Missile Crisis in the wider Cold War take humanity to the brink of destruction

What would happen, however, was an unprecedented economic disaster to wipe the smug ‘Roaring ’20s’ smile off Herbert Hoover’s face. The suave confidence of Hoover’s new administration was soon to sink into the mires of economic depression, and America would need to seek a new saviour, in the form of one Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

FDR, much like Wilson, seems resolved to haul America through thick and thin. “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself”, are the words which seem to emanate from his composed portrait. The 1960s presidents then return to a more hardened, graver image of the presidency, in a decade which would see the Cuban Missile Crisis in the wider Cold War take humanity to the brink of destruction. National concern is etched onto the faces of these burdened statesmen.

And then the mould appears to have changed – in several ways. From Nixon onwards, smiles begin to break out on the men to have held office. The image of Nixon from the Library of Congress gallery is different to those of his predecessors, in that it depicts a man who is rather chuffed to be president – grinning like the Cheshire Cat – rather than one honoured with a uniquely serious responsibility. After 1974’s Watergate Scandal, he would come to be seen a as a crook. However, his public-facing persona actually may not have been the most flattering from the off.

The other precedent set was the introduction of the prominent star-spangled banner behind the new office-holder. After the fiasco of Vietnam, this curatorial choice may have been intended to show the American people that they were again the priority. In front of the flag, the president becomes a sentinel, a guardian of the values the country holds to be ‘self-evident’. Only, Nixon didn’t quite keep up that pretence.

Jimmy Carter, criticised throughout his tenure for his weak nice-guy diplomacy, has an air of US television’s Mr Rogers about him, belittled under the towering flag yet looking very much like a grandad you’d want to have a coffee with – a humanitarian gem if not the most inspiring national leader. With the arrival of the Reagan years, however, up rises the posture again, and Carter’s nervous meekness gives way to an at-ease confidence. If anyone knew how to sculpt an image, it was a former movie star.

As both the 45th and 47th POTUS, Trump has received two official photographs – but, like the two-faced god Janus, the two Trumps couldn’t be any more different

The only president not to grin in recent times is Barack Obama. Taking office against the backdrop of the 2008 economic crash and the global War on Terror, Obama’s slight smile is not so reflected in his eyes. There is certainly a self-assured pride regarding his historic election, but beneath the surface one senses an urge to get started with the task conferred on him by the people. Of all the presidential portraits, Obama’s is arguably the most indicative of an ideal leader’s qualities.

And so we must now address the Republican elephant in the room – Donald J. Trump. As both the 45th and 47th POTUS, Trump has received two official photographs – but, like the two-faced god Janus, the two Trumps couldn’t be any more different. 2017 Trump is positively beaming, whereas the Trump of January 2025 is almost a carbon copy of his infamous 2023 mugshot. Much has changed in his political trajectory since the 2016 election, not least narrowly surviving two assassination attempts in the past year. Through a visual language of resistance and defiance, Trump’s team are signally a much more toughened administration to come, frowning upon all those who would go against him – perhaps imploring them to try.

The presidential portrait is no longer just a representation of a founding fathers’ desk job; it’s a political device, built either to endear or to scaremonger

Hindsight is involved in all these interpretations – that much is true. But a presidential headshot can prove very insightful as a harbinger of the coming four years, and as a medium to harness public support right out of the blocks. Mapped onto a president’s facial expression, posture, eye contact (or lack thereof), and carefully curated background, are clues to dissect, artistic choices to unpeel. Viewing Trump’s new-look portrait, unlike any other before it, we’d be amiss not to feel afraid. There’s something esoteric there, something stand-offish and aggressive, designed to unsettle. And Trump – one eye squinting, one eye wide open – appears to be inviting a challenge. The presidential portrait is no longer just a representation of a founding fathers’ desk job – it’s a political device, built either to endear or to scaremonger. I’ll leave you by resurrecting that age-old question: is it better to be loved or feared?

Comments