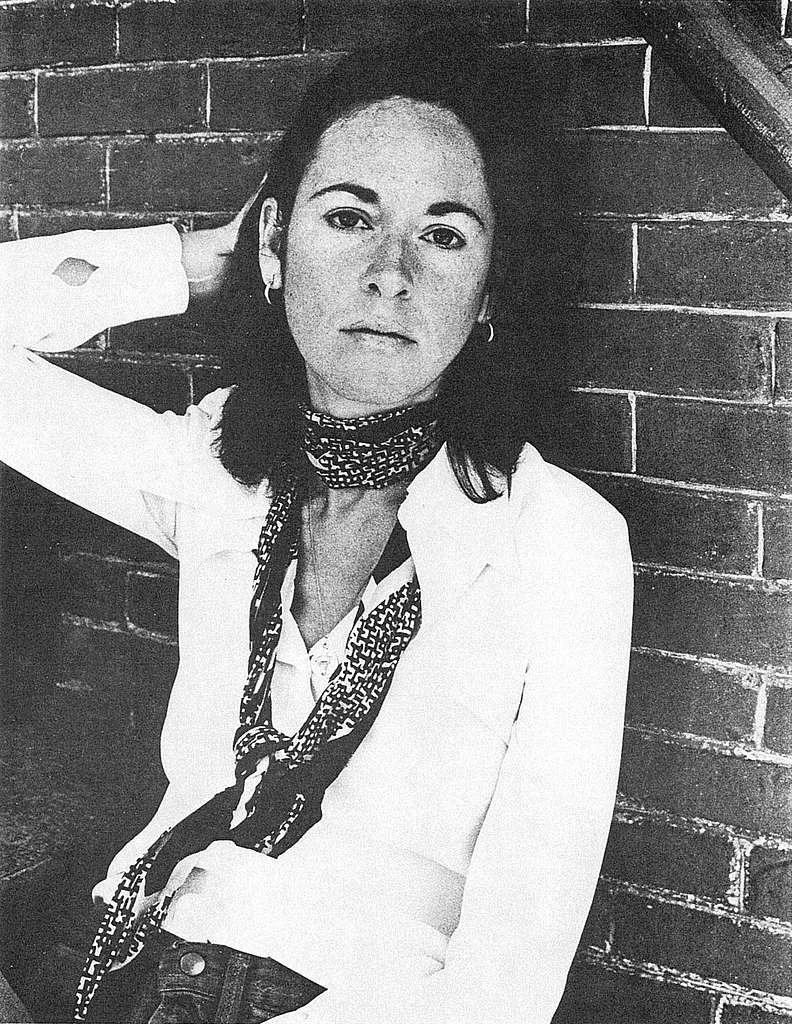

The Poetry Collection: Louise Glück: ‘doesn’t Joy, like fear, make no sound?’

Poet and essayist, Louise Glück was born in New York City in 1943 and grew up on Long Island. The arts were a focal point of her childhood and deeply encouraged within the Glück household. Reading at an early age was imperative to her development as an artist. Her parents would read Greek Myths to her, the story of Joan of Arc and her father taught her how to make up stories of her own. In her autobiography, Glück stated that ‘there was a sense in [her] house that art was a noble calling,’ further displayed by her undertaking of music, ballet, and art lessons at a young age. Later in life, She attended Sarah Lawrence College and Columbia University but left without taking a degree. However, at Columbia, she took classes with poets Léonie Adams and Stanley Kunitz, whom she credits with helping her find her own poetic voice.

Throughout her writing career, Glück published 13 books of poetry and became known as an autobiographical poet. Her most famous works, The Wild Iris (1992), won the Pulitzer Prize in 1993. Evolving into one of America’s most talented contemporary poets, Glück went on to obtain many other awards for her writing. These include her becoming the 12th US Poet Laureate in 2003, being awarded the National Humanities Medal by Barack Obama in 2015 and the Nobel Literature Prize in 2020. Glück sadly passed away in 2023, however, her literary legacy prevails.

Intrigued by such a prominent figure, I picked up Poems: 1962-2020 by Louise Glück, a hefty anthology of majority of Glück’s work spanning over her poetic career. The large period of time captured in this book allows readers to see the arc of her formal and thematic development within her poetry. The Guardian stated that to read Glück “is to encounter stillness and slow time”. The collection uncovers themes of sensitivity, loneliness, relationships, divorce, and death. Louise Glück is truly the poet of life and death – writing about all aspects of the human experience. Her technical precision and her imagery is what distinguishes her style from the masses. Glück likes to draw upon Greek mythology (perhaps influenced by her childhood reading habits) and natural imagery to convey her ideas. Her ability to take seemingly small images and wield them to form her own existential concepts of life is shown in her poem ‘The Silver Lily’.

Although I first encountered ‘The Silver Lily’ within her 1962-2020 collection, it originally derives from her most famous collection – The Wild Iris. Within The Wild Iris, Glück constructs a collection of poems that describe a year in and around a garden – focusing upon the intricacies of nature. In ‘The Silver Lily,’ Glück underlines themes of mortality and acceptance of this mortality. The poem’s most prominent quality is its use of natural imagery to convey these themes. The image of the moon is repeatedly mentioned throughout the poem in order to display these concepts of mortality:

Can you see, over the garden—the full moon rises.

I won’t see the next full moon.

White over white, the moon rose over the birch tree.

The motif of the moon elicits ideas of light and hope, however, through the solemn tone of the speaker this hope seems to be dwindling. The moon is a constant force in life, it is daily, quotidian, so the idea of not seeing “the next full moon” ties in with a recurring theme of death and endings that is laced throughout the poem. Despite this theme of death, Glück does not paint a morbid picture in her poem, rather there seems to be a mutual feeling of acceptance crafted between the speaker and the reader. The poem is set during a spring night, which is quite a contradictory setting. The idea of spring connotes change, flowers blooming and new life whereas the consistency of “night” and the “moon” contrasts with the spring. This contradiction furthers Glück’s messaging in the poem by suggesting that despite the change and the fleeting nature of life, certain things stay consistent – like nightfall. Glück’s philosophical convictions are outlined in the penultimate stanza as she expands beyond her detailed use of natural imagery.

We have come too far together toward the end now

to fear the end. These nights, I am no longer even certain

I know what the end means.

The collective pronoun “We” suggests that the speaker is now directly addressing the reader in an attempt to connect them to this newfound calm acceptance in not fearing “the end”. “The end” is quite an ambiguous phrase; it could mean the end of the winter bleeding into spring, it could mean the end of day turning into night, or it could mean the end of life. The speaker themself is “no longer even certain” they know “what the end means”, showing a shift in this certainty about life that has been laced throughout the poem. This moment of unsuredness uncovers a new sense of intimacy between the speaker and whomever they are addressing. This intimacy feels greatly personal as even this omnipresent speaker who speaks of the moon, the night, the spring, the trees, does not have an absolute answer for these questions that grapple between life and death. The poem looks at the constants in our life: the seasons changing, celestial figures, the concepts of day and night, and yet still ends with a sense of pondering. The speaker does not have all the answers shown through the deeply reflective tone in the poem, inviting the reader to also contemplate this mortality that Glück is touching upon.

Glück was the first American poet to be awarded the 2020 Nobel Literature Prize since T.S. Eliot “for her unmistakable poetic voice that with austere beauty makes individual existence universal”, certainly shown in her poem ‘The Silver Lily’ and many others from her 1962-2020 collection. Glück was an extraordinary literary figure who departed with 13 poetry collections that truly captured the human experience.

Comments (1)

A beautiful summary of a unique poet figure!