Root, form and body: an exploration of the Peggy Guggenheim Sculpture Garden

‘Se la forma scompare la sua radice è eternal’ – If the form vanishes its root is eternal. This 1989 neon sign by Mario Merz greets visitors as they enter the garden at the Peggy Guggenheim Museum in Venice. It invites one to explore the different sculptures in relation to each other, and ponder the distinction between form and root within the human body.

Curatorial layout aerial plan of Peggy Guggenheim Sculpture Garden, Marcus Stalmanis

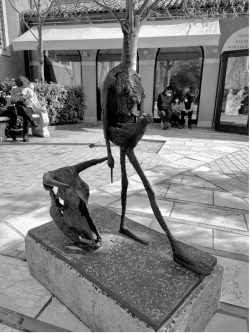

At the entrance of the garden is the 1936 Alberto Giacometti bronze Woman Walking. The slender figure is depicted as a recognisable human form of smooth skin and gentle curves. Her tentative step forward acts as a stark contrast to Germaine Richier’s bold Tauromachy (1953), which almost strides off its plinth. While Giacometti’s piece has a simple refinement and purity, Richier tears open the outer bodily shell to reveal the inner skeletal armature. The textures of the smooth pristine Woman Walking, and the disintegrating innards of Tauromachy, present an integral distinction throughout the garden – the division between external ‘form’ and the internal ‘root’.

Tauromachy (1953), Germaine Richier, Bronze

‘Tauromachy’ means bullfighter, which offers a narrative about the figure; a victorious matador with layers of symbolism to unravel. The work is openly morbid. A casted goat’s skull lies beside the bullfighter, who holds a spike freshly extracted from the animal. Curiously, the figure’s other hand is inserting a spike into its own torso. The action does not appear to be painful; there is no emotion or bodily expression. It alludes to the effect of the recent slaughter of the animal on the bullfighter’s inner spirit. This action shows the prey and victorious warrior inextricably linked, as the skull almost seems like it could complete the figure, fitting perfectly in place of its missing head. The different symbolic elements in relation to the body elusively explore the theme of death, destruction and bodily root.

Peggy Guggenheim embraced a vast range of artistic philosophies

Richier’s surrealism and Giacometti’s expressive figuration offer a counterpoint to the other abstract work in the garden. Peggy Guggenheim embraced a vast range of artistic philosophies. Abstraction and surrealism can be found alongside each other throughout the collection. This interplay of ideas encourages a less direct, more contemplative viewing experience.

Sphere No.3 (1965), Arnaldo Pomodoro, Bronze

On the opposite side of the courtyard from Tauromachy is Arnaldo Pomodoro’s 1965 bronze sculpture, Sphere No.3. The outer shell of gleaming perfection is cracked and ruptured, enabling discovery of a rich inner world. Pomodoro’s sphere sculptures have been interpreted as referencing planets or machine-like objects. It is not human in its appearance, but within the garden it becomes interconnected with the other figurative sculptures. The combination of the outer shiny roundness and inner eroded texture enlivens the piece, embodying the dynamic tension present throughout the garden.

Standing Woman (1947), Alberto Giacometti, Bronze

Giacometti’s Standing Woman (1947) is placed across from Sphere No.3 and his earlier Woman Walking, and diagonal from Tauromachy, completing the rectangular formation of these sculptures. The contrast with his earlier work, shows a curatorial decision to compare corrosion to smoothness, spindles to curves, aggression to passivity. There is a stark disparity between the headless, armless Woman Walking, made into a passive beautiful object, and the arresting confrontational appearance of Standing Woman, staring at the viewer. Giacometti’s changing sculptural approach resonates with Merz’s quote, ‘If the form vanishes its root is eternal’. Woman Walking’s fuller curved forms vanish in Standing Woman leaving this thin ethereal figure, almost like a remaining spinal cord. Standing Woman radiates this condensed human core, perhaps representing this inner root.

Amphora-Fruit (1946), Jean Arp, Bronze

The sculpture in the centre of the courtyard is Jean Arp’s 1946 Amphora-Fruit, a beautifully curved object that becomes a unifying point for the rest of the works. Its abstract organic form suggests a womb or an embryo, or even a more ethereal soul-like orb. Both Arp’s Amphora-Fruit and Giacometti’s Standing Woman embody the ‘eternal root’. While one presents a figure of crumbling chaos, the other shows a complete and organic whole. The difference between the works is not just an aesthetic challenge, but one that confronts the essence of the body in a metaphysical way.

The lone object can transcend into one that is part of an exciting conceptual framework where meaning can overflow

The shape of Arp’s work leads the viewer to walk around it and revisit the surrounding sculptures. The diagonal lines in the flooring draw connections between each work that inspire a comparative way of looking at the contrasting forms. This viewing approach alongside the broad idea of root and form, enables each work to conjure a complex interplay of ideas. The lone object can transcend into one that is part of an exciting conceptual framework where meaning can overflow.

Arp’s work gently angles towards the Byzantine throne which people are welcome to sit on. The throne solidifies the idea that the garden is not just for viewing sculpture, but allows for introspectively looking at one’s own human form. The visitor becomes part of the sculpture network, and when seated in the throne, imbues the artistic objects with another level of humanness.

Comments