Heartstrings and heroics: romance in superhero cinema

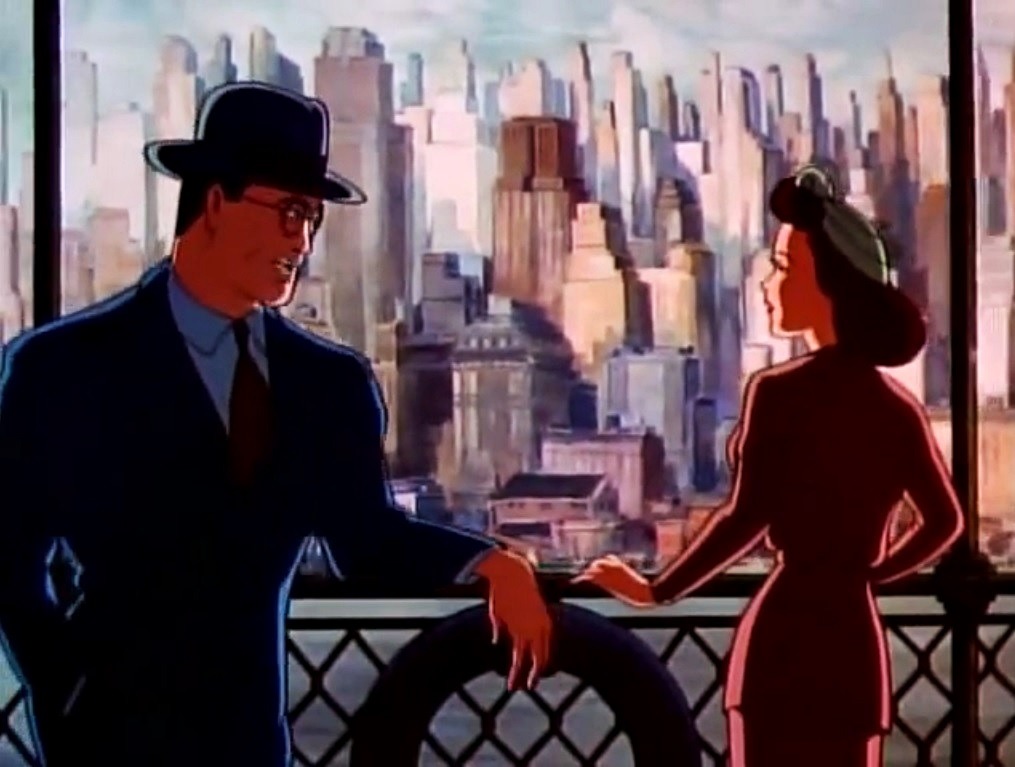

Heroism and romance are conceptually tied together in superhero cinema, with love serving as both a cathartic reward for heroic acts and as a catalyst for a hero’s humanity. In Spider-Man (2002), Tobey Maguire’s Spider-Man saves Mary Jane from vicious thugs and the pair share an iconic upside-down, rain-soaked kiss, while Maguire practically endures the horror of waterboarding behind his mask to capture the awesomely intimate scene. In Man of Steel (2013), Superman examines his humanity through his love for Lois Lane. She even heals the mental aggression and anguish he exercises against the Justice League in a state of confusion after his resurrection in Zack Snyder’s Justice League (2021). The love interest is always the second half of a hero, keeping them grounded and reinforcing the human part of being ‘super-human.’

The transcendent and relatable power of love and how it manages to cripple even the strongest figments of our imaginations

As with all romance, the superhero genre is not excluded from complexity. Despite feats of super speed or strength, romance is the roadblock. It weighs heavily on a hero’s heart. This allows us to inspect the transcendent and relatable power of love and how it manages to cripple even the strongest figments of our imaginations. Nothing demonstrates this better than the working-class hero of Peter Parker and his alter-ego Spider-Man. More than once, the pain of heartbreak has changed the powers and perspectives of Spider-Man and his relationship with the audience. None is clearer than the adaptation of the devastating death of Emma Stone’s Gwen Stacy, just over a decade ago in The Amazing Spider-Man 2 (2014).

The hero’s lover possesses and reanimates heroism and is a source of power when the hero is doubtful and insecure

Andrew Garfield’s talent and ability to depict overwhelming grief convinced my 10-year-old self, sitting in the theatre, that Spider-Man – for once – might not have a cinematically happy ending. The traditional damsel-in-distress structure I had grown up with was being subverted, leaving a pit of uncertainty and confusion in my younger self: this was not what happened in superhero movies. Despite the pain of loss Peter goes through, the film’s use of an acousmatic and ghostly echo of Gwen Stacy’s hopeful graduation valedictorian speech, which opened the film, becomes the cyclical catalyst for Spider-Man’s return to form at the film’s close. The hero’s lover possesses and reanimates heroism and is a source of power when the hero is doubtful and insecure.

Gwen Stacy and Lois Lane are recognised for their intelligence and influential female voices

Within the heteronormative sphere of comic book love interests, the female characters are usually subject to being infantilised or diminished into prizes and damsels to be saved by the hero. It is thus commendable when Gwen Stacy and Lois Lane are recognised for their intelligence and influential female voices. In the ideological battle between good and evil, the romantic love interest can bend the fabric of these super-human narratives and restore sense, compassion and hope within these fallible male characters. This is the reason why villains attempt to disrupt or destroy this romantic connection: they thrive off Machiavellian chaos, and their first move is to ‘attack the heart.’ This usually contributes to our subconscious hatred for these villains, as we observe their bitterness and malevolence through the unnecessary threats they pose to the innocent and wholesome power of love.

This power of love often embodies a poetic form of irony within superhero media. For example, Captain America gets frozen for decades fighting the evil of fascism, only to return to the modern world where he is stripped down to Steve Rogers, longing for the date he was supposed to have with his sweetheart Peggy. The simple, tragic beauty of that final scene in Captain America: The First Avenger (2011) is emotionally poignant if nothing else. To a character so bound by honour and loyalty, the pain of New York’s modernity hurts the hardened super soldier in a way that a fascist bullet never could: it erases the time he wanted to spend with the love of his life. Another example is within Iron Man 3 (2013) when Tony Stark blows up his suits (along with the villain) at the film’s climax and finally has the surgery to extract the reactor threatening his heart. He does this all for the trust and love he bears for his girlfriend, Pepper Potts.

Love is a wonderfully unstable and unpredictable property, and that mixes well with informing the arcs of superhero characters. In Avengers: Endgame (2019), Iron Man chooses to sacrifice himself, despite being a family man, for the greater good of the world. This culminates in a beautifully structured slow zoom, entering the home of Steve and Peggy. We watch the couple’s intimate slow dance, something the hero has been chasing for virtually a decade on screen. This shot closing the modern superhero epic that is Avengers: Endgame, illustrates the cathartic and poetic beauty love holds against adversity within superhero cinema.

Comments