Kneecap: Outrageous in English, unforgettable as Gaeilge

Anotion oft-attributed to Sigmund Freud had described the Irish as, unlike any other race, impervious to psychoanalysis. For instead they would turn to storytelling and poetry to escape any kind of psychic trouble. So as riotous as it is righteous, Kneecap may not possess the lexical ornateness of Wilde or stylistic complexity of Heaney, but the group’s take on such storytelling presents a gloriously entertaining piece, if you pardon the adverb, of ‘Fine Art’.

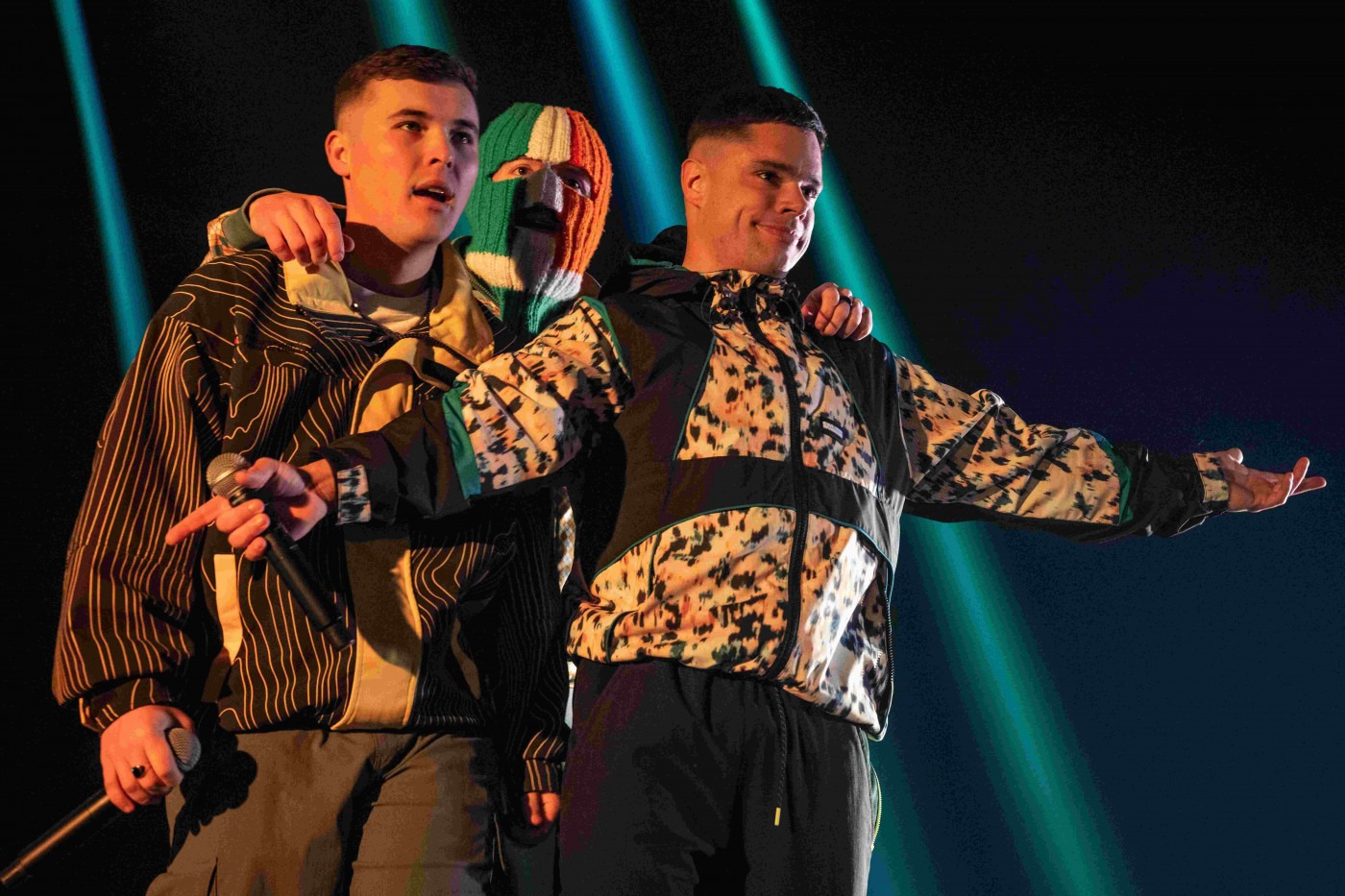

In the shadow of the Troubles, ‘ceasefire babies’ Liam Óg Ó hAnnaidh, Naoise Ó Caireallain, and J.J. Ó Dochartaigh star as themselves in Rich Peppiatt’s latest project; it is a semi-fictionalised retelling of the origins of up-and-coming Irish language rap group Kneecap. But ‘music biopic’ would be a fairly limiting label for the eponymous film; it is an impressive balancing act between a boisterous coming-of-age story and poignant reflection on the lingering impacts of the conflict that still loom over the North of Ireland, or Northern Ireland for those on the other side of the wall.

By no means would the film be suitable for anyone who’d consider themselves faint of heart

Initially, the film might appear to be little more than a glorified music video, with flashy visuals and a focus on the band’s electrifying stage presence that admittedly prompted questions of whether the picture would be more of a gimmick than a cinematic endeavour.

But from their origins in West Belfast’s small Gaeilgeoir community – those are native Irish speakers for the uninitiated – protagonists Liam and Naoise become Mo Chara and Móglaí Bap, swept along by their own music teacher, JJ (later the balaclava’d DJ Próvaí). In the true essence of Kneecap, acting as Irish interpreter following a run-in with the police, he discovers Liam’s incendiary rap lyrics scribbled as Gaeilge in his notebook.

But it is not in spite of, but hand in hand with the endurance of the Irish language that the film’s explosive style and graphic humour goes

By no means would the film be suitable for anyone who’d consider themselves faint of heart, with its rambuctious, vulgar performances punctuated with running jokes and graphic portrayals of decadent ketamine use, although hardly surprising for a group whose name derives from an infamous torture technique used by paramilitants in the Troubles. Sex scenes are liberally sprinkled throughout, often accompanied by particularly coarse references, like one to the Brighton Hotel bombing, that never allow the viewer to forget the ubiquitously persisting political tensions that frame Kneecap’s Belfast.

But it is not in spite of, but hand in hand with the endurance of the Irish language that the film’s explosive style and graphic humour goes. Uncompromising in its refusal to sanitise Gaeilge, Kneecap perhaps present a more profound commentary on language revival; that true decolonisation lies not just in resurrecting a language once suppressed by British rule but in using it to express the full spectrum of human experience, from the sublime to the profane, from the joyous to the deeply unsettling.

Thus Kneecap offers a compelling space for the Irish Republican identity to reassert itself in peacetime, illustrated by the call and response between Naoise and his father that bookends the film: “Gach focal a labhraítear i nGaeilge… is é piléar scaoilte ar son saoirse na hÉireann” — Every word of Irish spoken… is a bullet fired for Irish freedom.

Ireland’s fraught past is inescapable in defining contemporary national identity

Through fleeting details – a Palestinian flag draped over a Belfast tower block, seemingly throwaway jokes about “sellout” Michael Collins, or a deeply symbolic dinner table confrontation – Ireland’s fraught past is inescapable in defining contemporary national identity. One particularly poignant scene sees Liam’s Protestant lover, Georgia, refuse to “take the soup” at her Ulster Loyalist and PSNI detective aunt’s dinner table, a chilling nod to the practice of Souperism during Ireland’s Great Famine, where starving children were fed in exchange for Protestant religious instruction. Perhaps emblematic of a rejection of sectarianism from this “ceasefire generation”, the shadows of history prove a platform, not an obstacle, for Kneecap’s exploits – as outrageous as they are political – and a movement for an Irish language for all.

The film’s soundtrack, including now Oscar-shortlisted track Sick in the Head, is of course a standout element, serving to score Kneecap’s unrelenting energy in its quest to make Irish nationalism cool again. And in a remarkable reception for the first-time actors, the group have garnered some significant critical acclaim, their second Oscar shortlist for Best International Feature cementing its place in the cultural movement.

For international viewers, Kneecap may stand just as the hilariously provocative narrative it is, but for Irish audiences, particularly Gaeilgeoirs, it offers something far more profound, a reflection on the current standing and enduring value of a centuries-old language. This is the essence of Kneecap: unapologetically raw, honest, and resolute in its celebration of Irish language and identity, making their voice, and Gaeilge, more raucous than ever.

Comments